A dairy waste byproduct presents sweet potential — and sour challenges — for the alcoholic beverage industry.

Wisconsin doesn’t get much more prototypically rural than Knowlton. Farmland and forest surround the settlement of about 2,000 people, and it lies over 100 miles west of Green Bay, the closest major city. Still, Heather Mullins insists that Knowlton has life’s essentials.

“A cheese factory, a bar, a gas station, and a church. That kind of makes up a Wisconsin town,” Mullins jokes. She’s given Knowlton the second entry on that list through the cocktail lounge at Knowlton House Distillery, which she co-founded with her husband Luke in 2023.

Luke Mullins also works down the street at Mullins Cheese, where he helps run the state’s largest family-owned cheese manufacturer with his father and three brothers. The two businesses have become tightly connected, and not just through marriage: Knowlton House specializes in crafting spirits from whey, a byproduct of cheese and yogurt production, sourced from the Mullins factory.

Heather Mullins’ TenHead vodka, a smooth sipper with just a touch of creamy sweetness indicative of its origin, boasts multiple platinum and gold awards from international competitions. “Potato vodka doesn’t taste like potatoes, and milk sugar vodka doesn’t taste like milk,” explains the distiller. “It just has some of those underlying, nuanced, silky textures that come from that source ingredient, which we think are really special.”

Outside of Knowlton, however, whey often gets treated as a problem rather than a potable. Dairies make far more whey than they do actual products, roughly 9 pounds for every pound of cheese and up to 4 pounds for every pound of yogurt. Handling that excess often means spreading it on agricultural fields or sending it into wastewater treatment systems. Although whey can add nutrients to farm systems, too much can make soils more acidic. If whey runs off into waterways, it reduces available oxygen levels, causing fish kills and other damage.

Producers are increasingly seeking ways to make whey more valuable and less environmentally concerning. Some market it directly as a beverage, like the “probiotic tonics” sold by Brooklyn’s The White Moustache. Whey holds usable amounts of protein, which Mullins Cheese and other larger producers can extract for sale. It also carries sugar in the form of lactose — and where there’s sugar, there’s the potential for alcohol.

The concept of fermenting whey isn’t exactly new. Lars Mairus Garshol, an author who specializes in traditional European brewing history, notes that Norwegians and some Scots regularly drank a mildly alcoholic whey ferment called blaand, aka “milk mead,” from at least the time of the Vikings through the early 20th century. But they abandoned that practice, he writes, as modernity made higher-status alternatives like juice and coffee more widely available.

In the 1970s, the Irish dairy company Carbery redeveloped whey fermentation at an industrial scale, adding on a distillation process to make high-proof ethanol for beverages and biofuel. That approach also caught on in New Zealand, where Lactanol now produces 15 million liters of whey-based alcohol annually. Boutique producers in both countries sell upmarket whey-based liquor, such as New Zealand’s Broken Shed vodka and Ireland’s Bertha’s Revenge gin.

“Potato vodka doesn’t taste like potatoes, and milk sugar vodka doesn’t taste like milk.“

Yet while at least one manufacturer, Cayuga Ingredients in New York, is fermenting whey on an industrial scale, whey alcohol has yet to make a widespread impact in the U.S. Lisbeth Goddik, head of the food science and technology department at Oregon State University, believes that may be due to the country’s abundance of cheap corn used for ethanol. There’s little economic pressure, as in small island nations like Ireland, to explore the whey waste stream as a feedstock.

Goddik’s OSU colleague, chemist Paul Hughes, points out that whey also brings unique challenges to the fermentation process. He’s mentored several graduate students through projects aimed at refining whey fermentation and distillation on an artisan scale.

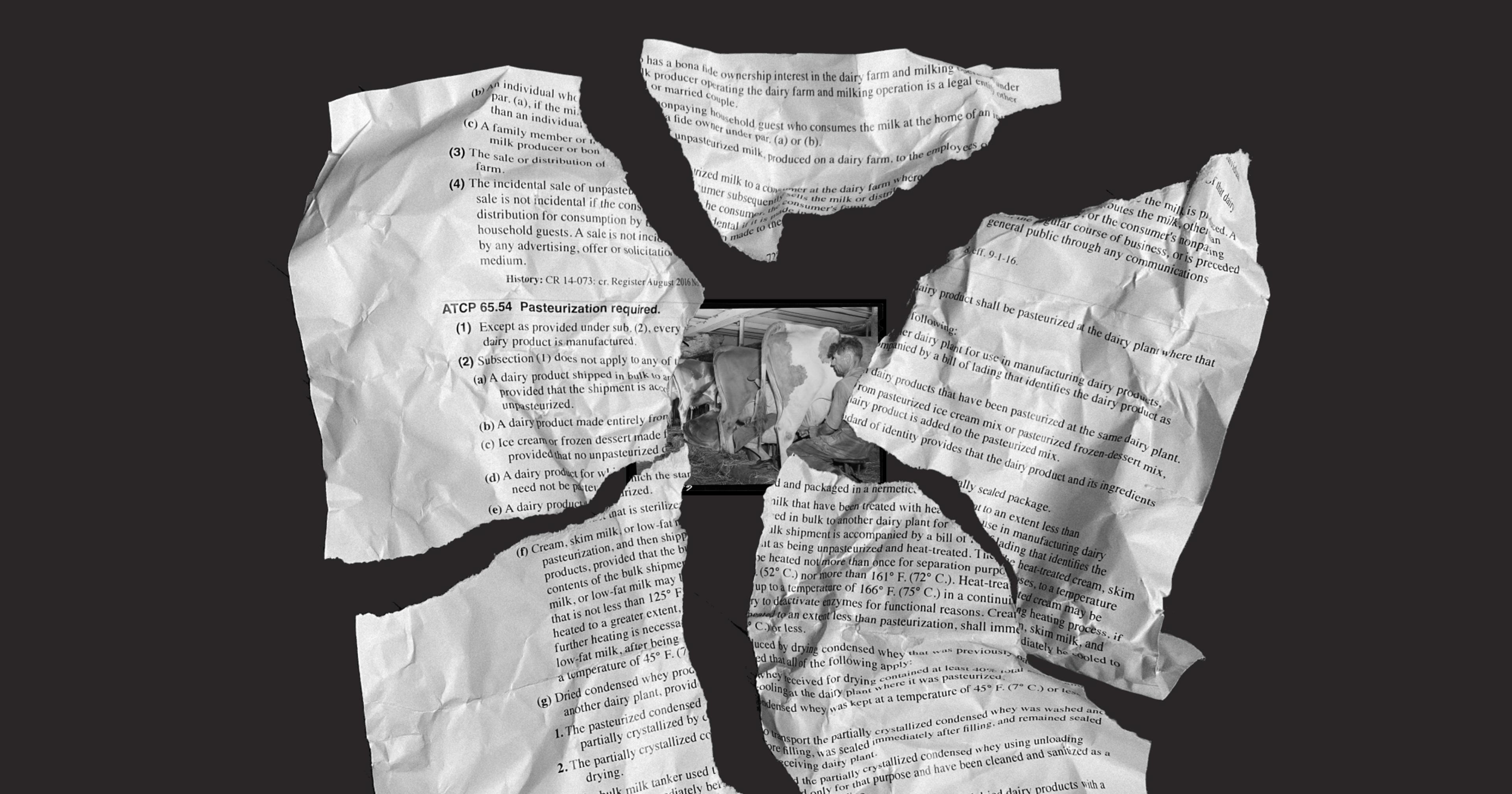

Traditional brewers’ yeast can’t break down lactose, Hughes explained, so processors have to either add the enzyme lactase (the same active ingredient in human lactose intolerance medications) at additional cost or work with yeast species that are less well-understood. When heated, he adds, whey’s proteins have a tendency to cling together, fouling equipment and leading to unpredictable hot spots in the mixture.

“This can cause ‘bumping,’ which is the violent release of boiling liquid. This is bad for your health,” Hughes says with dry humor as he recounts an early experiment.

To avoid such issues, most of those fermenting whey work with whey permeate, which is left over when cheese manufacturers filter out its proteins. That’s true for both Knowlton House and fellow Wisconsin distillery Copper Crow, operating near the shore of Lake Superior in Bayfield.

Copper Crow co-owner and distiller Curtis Basina sources his permeate from the Burnett Dairy Cooperative, nearly a three-hour drive away in Grantsburg. Despite the distance, Basina says, it makes more sense to buy the already-filtered product from that larger facility than it does to buy raw whey from closer, smaller cheesemakers. “If [Burnett] didn’t further those processes, it wouldn’t be economically feasible for me,” he explains.

“I love the idea that we’re playing our small part in that puzzle to find a diversified use for the whey.”

Basina says distilling from whey permeate still takes longer and is more expensive than making liquor from cane sugar or a corn mash. But the resulting products have attracted a strong customer base since he started offering them in 2017 — especially his whey-based amaretto, which he says tourists often buy by the case.

The permeate approach works, says Goddik, but there are limits to its widespread adoption. The machinery for filtering whey and isolating proteins is too expensive for most smaller dairies. And while it works well on the sweet whey left over from hard cheeses like cheddar, it’s much less effective on the acid whey remaining from products like cream cheese and Greek yogurt, which has a lower pH and higher mineral content.

Goddik and Hughes have successfully fermented and distilled raw acid whey, but the few commercial efforts to work with it so far have foundered. Harry Gorman, master distiller for Vermont Spirits in eastern Vermont, experimented with distilling acid whey from a nearby Cabot Creamery facility in the early 2000s but says he struggled with contamination and low yields. (He ended up producing a white whey vodka by redistilling Irish-produced whey spirits.) The whey-based Norwhey Nordic Seltzer, an alcoholic beverage launched in 2022 by Cornell University researcher Sam Alcaine, is no longer on the market.

Even the producers who’ve managed to carve out a successful whey-based alcohol niche say it’s important to keep their contributions to managing the waste stream in perspective. Heather Mullins, for example, says she works in 2,000-gallon batches; Mullins Cheese goes through 7 million pounds of milk each day, or well over 800,000 gallons. The USDA estimates that the country produced 14.2 billion pounds of cheese and 4.6 billion pounds of yogurt in 2023, resulting in roughly 140 billion pounds of whey overall.

“I’m not trying to tell the public that I’m saving the world with my vodka,” Mullins says. “But I love the idea that we’re playing our small part in that puzzle to find a diversified use for the whey — and, I’d say, a very delicious use.”