A police officer turned psychedelic mushroom farmer navigates his newly legal crop in Oregon.

Even a farmer whose produce grows entirely indoors can sometimes find himself at the mercy of the weather.

Gared Hansen looked a touch frazzled, yet still upbeat, as he Zoomed with me from the cabin of his truck in mid-January. A winter storm the previous week had knocked out electricity for tens of thousands of customers across the Pacific Northwest, including Uptown Fungus, the facility he owns and operates east of Springfield, Oregon.

“We’ve already been out of power so long that the generator ran out of propane,” he said with an exasperated chuckle. “I’m going to be taking a little hit in my production until I get power back.”

Thankfully for Hansen, his crop is perfectly happy to spend extended periods without the lights on. Uptown Fungus exclusively produces Psilocybe cubensis, the best-known species of psychedelic “magic mushrooms” — no photosynthesis required.

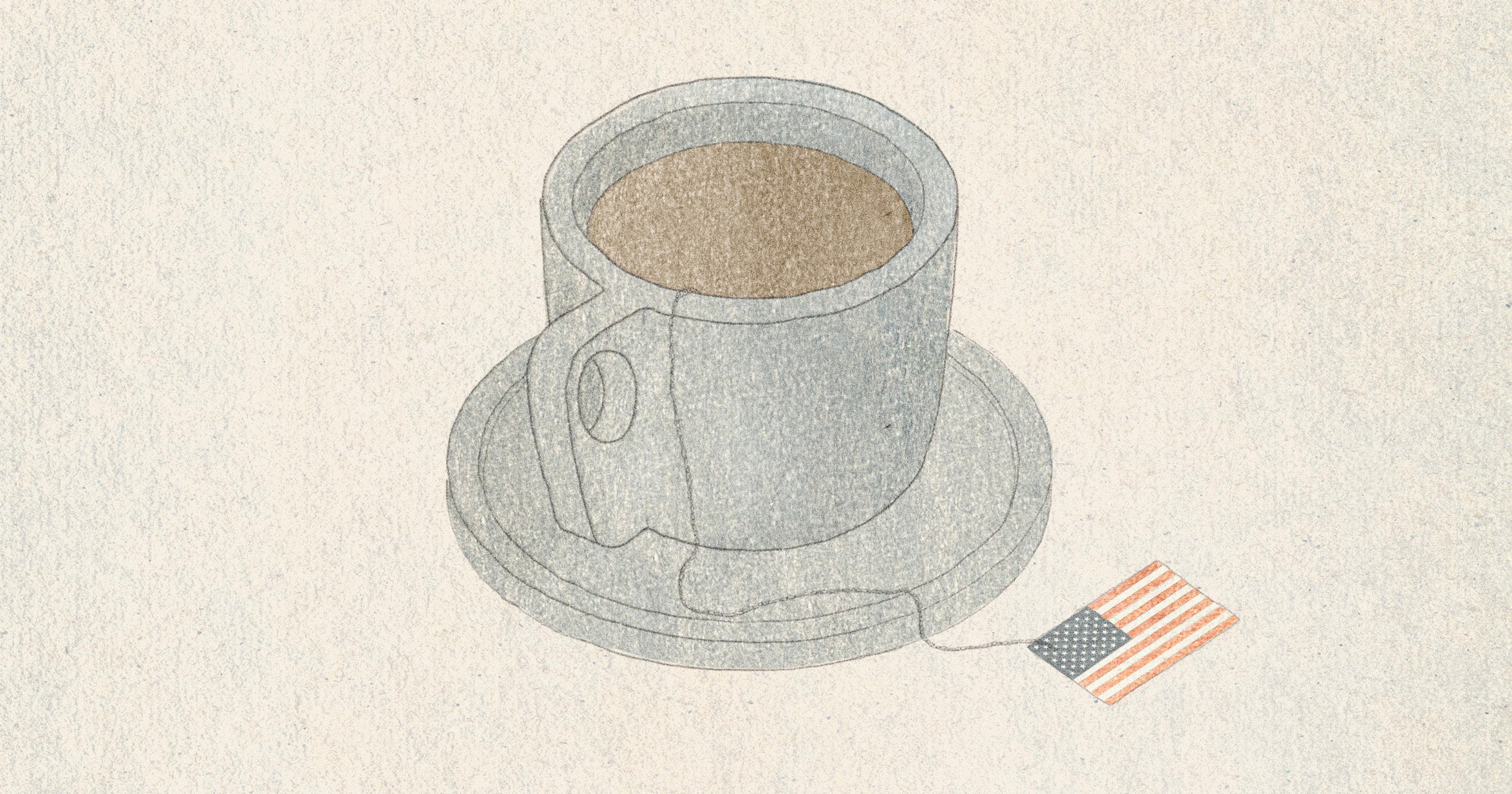

The business is one of just seven growers Oregon has approved since launching the country’s first psychedelic access program last year, an effort approved by the state’s voters in 2020. Although magic mushrooms remain outlawed at the federal level, any Oregon resident or visitor over age 21 can now legally take them at one of 21 licensed service centers under the eye of a trained facilitator.

Both clients and prospective psychedelic workers have shown overwhelming interest in the new industry. EPIC Healing Eugene, the state’s first service center, has roughly 3,000 people on its waitlist, each willing to pay up to $3,400 for a guided, legal trip. Angela Allbee, who leads psychedelic regulation for the Oregon Health Authority, said her staff has received over 1,050 applications for different licenses under the program, including 34 from would-be mushroom growers. (There is no cap on licenses, so everyone who works through the process should eventually get approved.)

At the heart of this rapidly expanding market, emphasized Allbee, is an agricultural product. “We don’t allow for chemical synthesis [of psilocybin, the main psychedelic compound in mushrooms],” she said. “As we wait to learn more from research on natural products, we’re able to really move forward with what has been used for centuries in the unregulated space.”

Hansen became quite familiar with the unregulated mushroom industry through his previous job as a police officer in San Francisco. But toward the end of that career, he said, a group of friends shared with him the powerful healing and spiritual experiences they’d had using psychedelics. He’d been starting to explore spiritual traditions like tantra and energy work, and he soon became enthusiastic about mushrooms as part of that journey.

Looking for a fresh start after retiring to Oregon in 2021, Hansen saw a chance to bring healing to others via psychedelic production. A hobbyist vegetable gardener with a penchant for tomatoes, he’d never before grown shrooms, but he brought himself up to speed by consulting with a professional mycologist and researching the process online.

“Is there any way you can get up here in the next few days? Our clients are just really eating through mushrooms!”

Uptown Fungus received its state license in April and now provides product to eight service centers, the only entities permitted to buy directly from manufacturers. Hansen estimates his current monthly sales at about $15,000, with prices averaging $4.25 per milligram of psilocybin those mushrooms contain. (A single dose is usually 20-30 mg, or about $85-$128 at wholesale.)

Mushroom growing itself, Hansen said, is relatively simple. His entire operation fits in a wood-walled outbuilding with about 500 square feet of floor space, divided into a larger workroom and smaller grow room.

Hansen inoculates soaked grain with Psilocybe spores, adds that spawn to plastic bins filled with coconut husk fibers, and waits about three weeks for the fungus to transform those raw materials into mushrooms before harvesting, drying, and packaging. His biggest challenge is contamination from ambient mold, a “green fuzz” that he says claims 5-20 percent of his crop despite careful sterile technique.

One of Uptown Fungus’s biggest clients is Fractal Soul, a service center in the Portland metro area that opened in October. Kat Thompson, the center’s director and CEO, said she recently placed her largest mushroom order yet, about $3,500, in anticipation of an uptick of demand for late winter.

All of Fractal Soul’s prospective suppliers offer a similar range of dried mushrooms; although extracts and mushroom-infused edibles are allowed under Oregon law, they require additional permitting through the state Department of Agriculture, which no manufacturer has yet completed. Hansen distinguished himself in the marketplace, Thompson said, through responsive customer service and a willingness to roll with the growing pains of a new business.

“I’ll take my chair into the mushroom room, sit, and try to bring up energy through my body and impart it into the mushrooms as a kind of healing energy.”

“I’ve had to send a few late-night emergency emails when we’re going through product faster than we thought we would,” Thompson recalled with a laugh. “‘Is there any way you can get up here in the next few days? Our clients are just really eating through mushrooms!’”

While service centers can also be licensed as manufacturers, potentially allowing them to supply themselves and cut costs, so far only one, Satya Therapeutics, has pursued that vertical integration. Thompson said mushrooms only represent about 15 percent of Fractal Soul’s overall expenses, and she’s happy to let dedicated farmers like Hansen handle production so she can focus on working directly with clients.

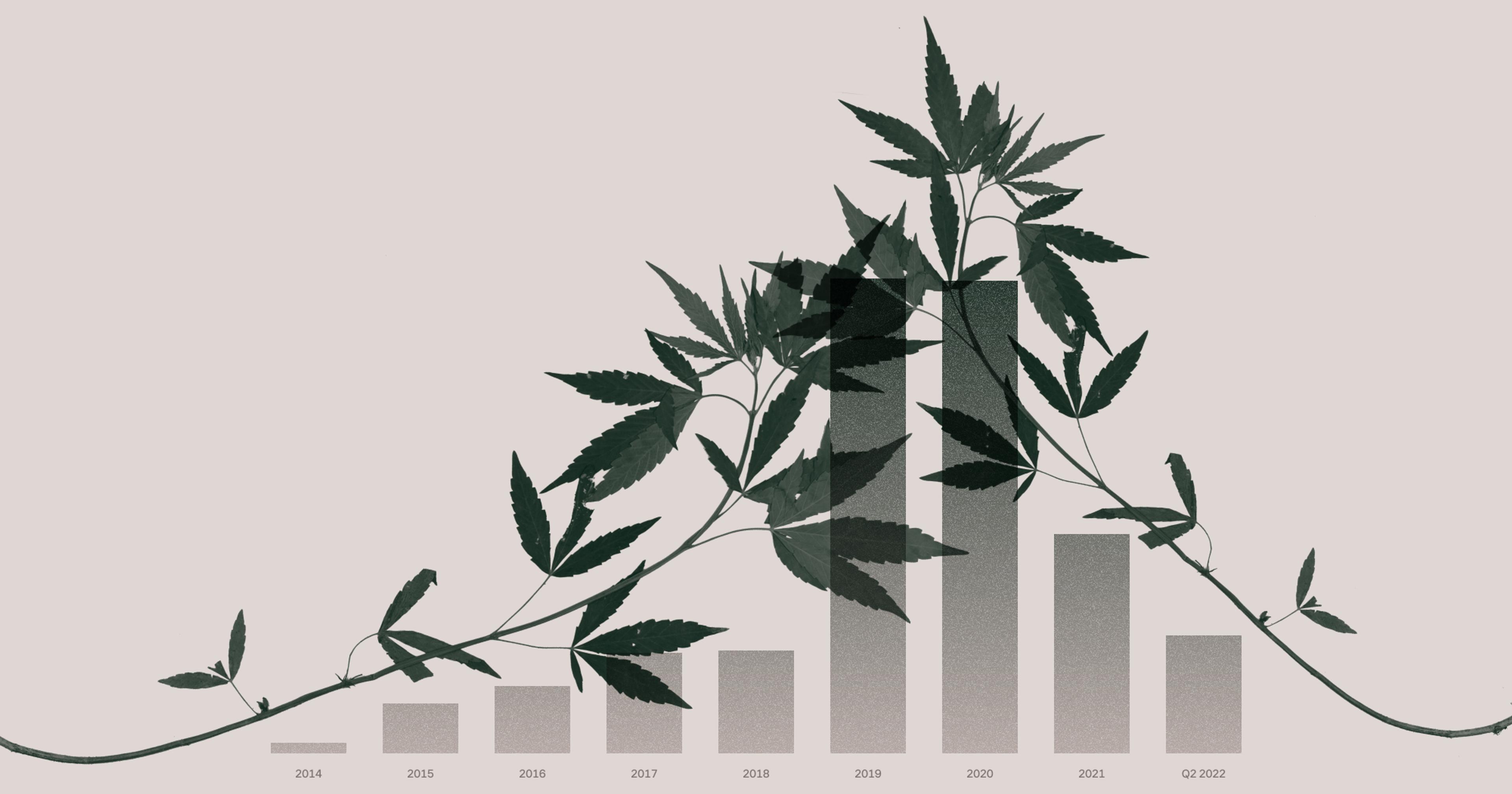

As Oregon’s experiment continues to unfold, other states are watching closely — particularly Colorado, whose voters approved legalizing mushrooms in 2022. Shannon Gray, spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Revenue, says Oregon’s regulators have willingly shared their expertise, and the state hopes to finalize its own rules for mushroom growers by October.

Some pain points have already emerged in Oregon. Only two labs are licensed to perform the legally required potency and safety tests for each batch of mushrooms, meaning the entire industry could bottleneck if those facilities were to shut down.

A manufacturing license is also relatively expensive, at $500 to apply and $10,000 each year, a potential obstacle for former black-market growers looking to join the legal industry. (Similar issues with access to capital have also arisen in states with legalized marijuana programs.) Allbee, Oregon’s head psychedelics administrator, said veterans and low-income applicants are eligible for reduced fees; the state also doesn’t consider certain prior convictions for mushroom or marijuana production in its applicant background checks.

Yet for Hansen, the chance he took on the mushroom industry is paying off. His sales have steadily gown, and he plans to bring on a part-time employee soon. He’s gearing up to renovate his facility and get approval for new offerings like mushroom chocolates.

And he believes what he’s doing represents more than just an agricultural business. The Uptown Fungus facility includes a small shrine with a tantric statue of a woman sitting in a man’s lap, both meditating — a focal point for a key part of his growing process.

“I’ll take my chair into the mushroom room, sit, and try to bring up energy through my body and impart it into the mushrooms as a kind of healing energy,” Hansen explained.