“Fatwood” is a popular all-natural firestarter, created when broken old pine trees leave a resin-filled deposit behind. Is foraging enough to satisfy growing demand?

Anyone who has heated their house with wood or tried to start a campfire is familiar with the process. You build up a bed of newspaper, twigs, and kindling, settle a few smaller logs on top and try to light it in the right spot so it sparks into a bright flame, quickly growing tall with satisfying snaps and crackles. But, as often as not, getting that fire crackling this requires a few rearrangements of the pile and quite a few strikes of the matches.

That is, if you haven’t heard of “fatwood,” aka dried pinewood full of resin. The material is also known as fat sticks, heart pine, or lighter wood. The colloquial term fatwood is used to describe how these small pieces of wood are so saturated with resin that they overflow with the sticky and highly flammable sap. While today it is most commonly used as a firestarter, fatwood can be carved and is sometimes burned down to produce pine tar.

“When I first started out,” said Peter Forrester of Forrester Bushcraft, a teacher of primitive living skills with a popular Youtube channel, “the first thing I learned was you have to go into boggy areas where a pine tree has died, and all the sap has dripped down into the roots. But that way, you have to pull it out of the bog and dry it. I think that’s the most traditional way of harvesting it.”

Fatwood develops where a tree has broken or been damaged and the sap of the pine tree rushes to the wound to help the tree heal. As the branch or tree dies, this resin settles and creates deposits of fatwood, where the resin content of the wood is much higher than a typical tree branch. It can take up to five years for the resin to thicken and harden into what is harvested as fatwood. While foragers typically look to the broken branches low in a tree for fatwood deposits, commercially available fatwood is often gathered from stumps left behind as waste after a logging operation.

Fatwood was first popularized as a commercial export in Scandinavia, with Sweden harvesting it for pine tar production in the 17th century. This is thanks largely to simple geographical happenstance, as Sweden has largely coniferous forests that are more than 35 percent pine. Anywhere you can grow most pine tree species, you can produce fatwood.

“Most pines have fatwood,” explained Shlisa Shell, who goes by ‘The Fatwood Queen’ on her Youtube channel and the Etsy shop where she sells fatwood bundles. She explains that fatwood deposits can be found in most places where pine trees grow, although the quality of the fatwood depends on the species of tree. The more resinous the genus of pine, the better the fatwood, said Shell.

“The main way to find it,” said Forrester, “is to look for those dead branches on the bottom of a tree. That is the easiest way to get it. You don’t get a lot of them, but it’s enough to start a little fire.”

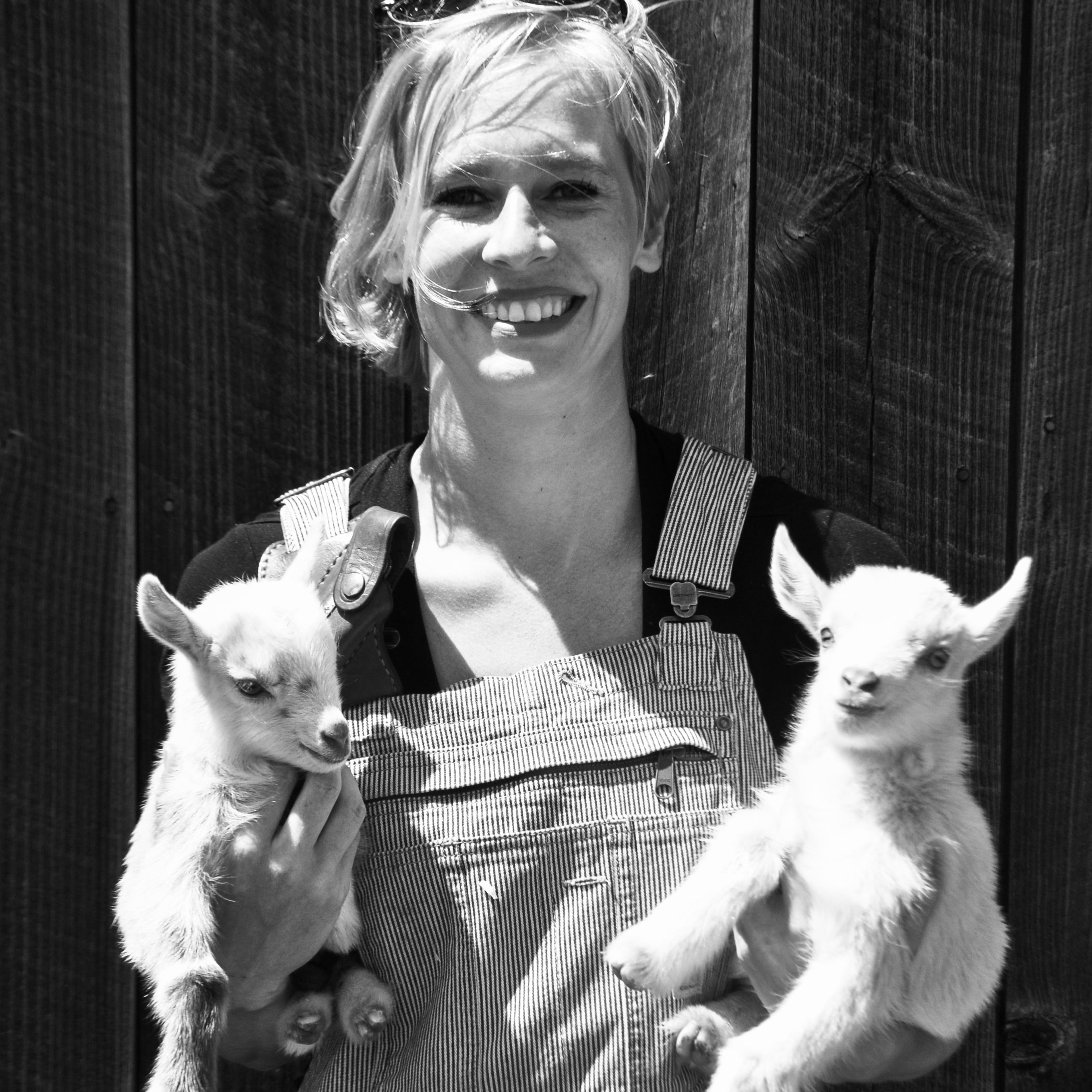

Photo by Kirsten Lie-Nielsen

“Sometimes you’ll see these little flat pieces of wood sticking out of the ground,” said Forrester, “and when you feel them they are hard, even though they look rotten. Give them a squeeze. They’re really rock solid. So you can cut those open, and there’ll be these rich deposits of fatwood in there.”

Fatwood can help you start a campfire in the wilderness, but its ability to get a home woodstove going is what makes it a lucrative target for the forager. Shell, the Fatwood Queen, sells one-pound bundles on her Etsy shop as well as larger single pieces for carving. Rather than struggling to sell the bundles, her greatest difficulty is keeping up with demand. “I am not always sure where I’m going to get the next batch,” she admitted.

While many people don’t know about fatwood, those that do are crazy about it, and Shell is part of an online community which carves, burns, and collects fatwood. The material carves and whittles down fairly easily and can be used to make spoons and bowls that have a translucent glow of pine resin. Shell has carved faces into small chunks, and says a thin piece of fatwood makes a striking window decoration as it glows in the sunlight.

As a purveyor of fatwood, Shell said the biggest challenge is finding enough of the material.

“Some people have it, and they just don’t know how to find it or they don’t realize they have it,” she said. “It took me 10 months here in Michigan to really realize that I have it everywhere. I imagine for some people, it’s all around and they just don’t notice it if they don’t know what they’re looking for.”

Commercially available fatwood often comes from South America, said importer Mark Hoogstra. There, fatwood is a waste material of the logging industry. Large packages of fatwood for the homeowner can be purchased from places like Lowes, Home Depot, LL Bean, and Orvis. These are mostly imported from Honduras, according to Hoogstra.

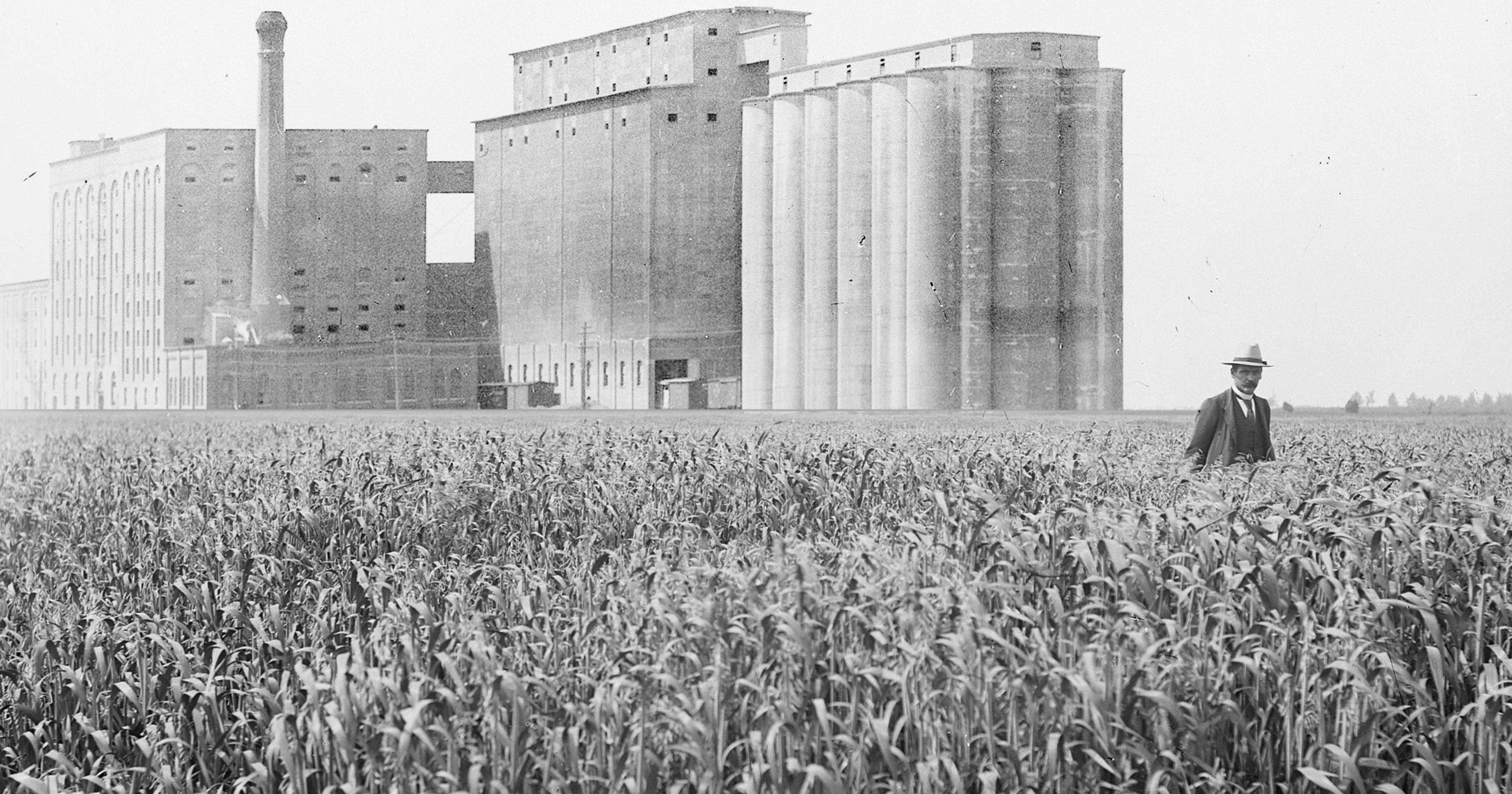

Photo by Shisla Shell

When it comes to lighting a fire, you want to use two or three sticks of fatwood to get the flame going and then add your traditional firewood. Using fatwood as firewood is impractical at best, given its small quantities and the fact that, because it is so resinous, it smokes heavily.

“It’s for just getting the fire going,” said Forrester, “It is literally one of the best things you can find in nature. It is absolutely fantastic stuff and there’s no downsides to it at all — even when it is wet it will burn.”

Forrest has done experiments starting fires in the rain with fatwood, and even dunking the sticks underwater and then lighting them. They still light up.

For her Etsy business, Shell visits five properties to scout for fatwood. She admits the wood could be cultivated, but it would take too much time to become harvestable to be considered a sustainable enterprise. Instead, she mostly walks the forest looking for broken off, dead branches. Ideal spots include areas along the highway where trimmers are used to keep the woods cut back, creating new damaged pieces of wood as they go.

Because of the time it takes for damaged pieces of pine to develop into fatwood, the material is difficult to cultivate at a scale, and foragers can struggle to find a dependable source of the material. However, it can be a profitable side hustle for a forager or anyone with access to pine forests. Etsy, farmer’s markets, and Facebook have plenty of small-scale sellers of fatwood, and enthusiasts of the outdoor lifestyle search their land and provide themselves with this unique, all-natural lighter wood.

Whether you’re desperately trying to start a campfire in the wilderness or just hoping to get the fireplace roaring for a holiday meal, fatwood never fails to impress. Just don’t tell too many friends, or it’ll be even harder to find.