As Big Ag gets bigger, who do small farmers turn to for their equipment needs?

For the first half of the 20th century, small American farms relied on small equipment. With inventions like gas-powered engines still getting their bearings, mechanized tractors like the John Deere D started on the smaller side. But as monoculture farming practices exploded after World War II, tractors and harvesting machinery grew along with newly expansive farms. Once-common equipment, like the single row corn harvester, became a relic of history for farms now expanding into hundreds, even thousands of acres.

In 1930, the average farm size in the United States was around 156 acres. By 1950, the average size rose to 215 acres, and in the 1970s, it rose to 440, just slightly under the 2022 average of 463 acres, per the U.S. Census of Agriculture. And yet while the average farm size has climbed, many farms are much smaller: 802,000 farms in the U.S. are between 1 and 49 acres.

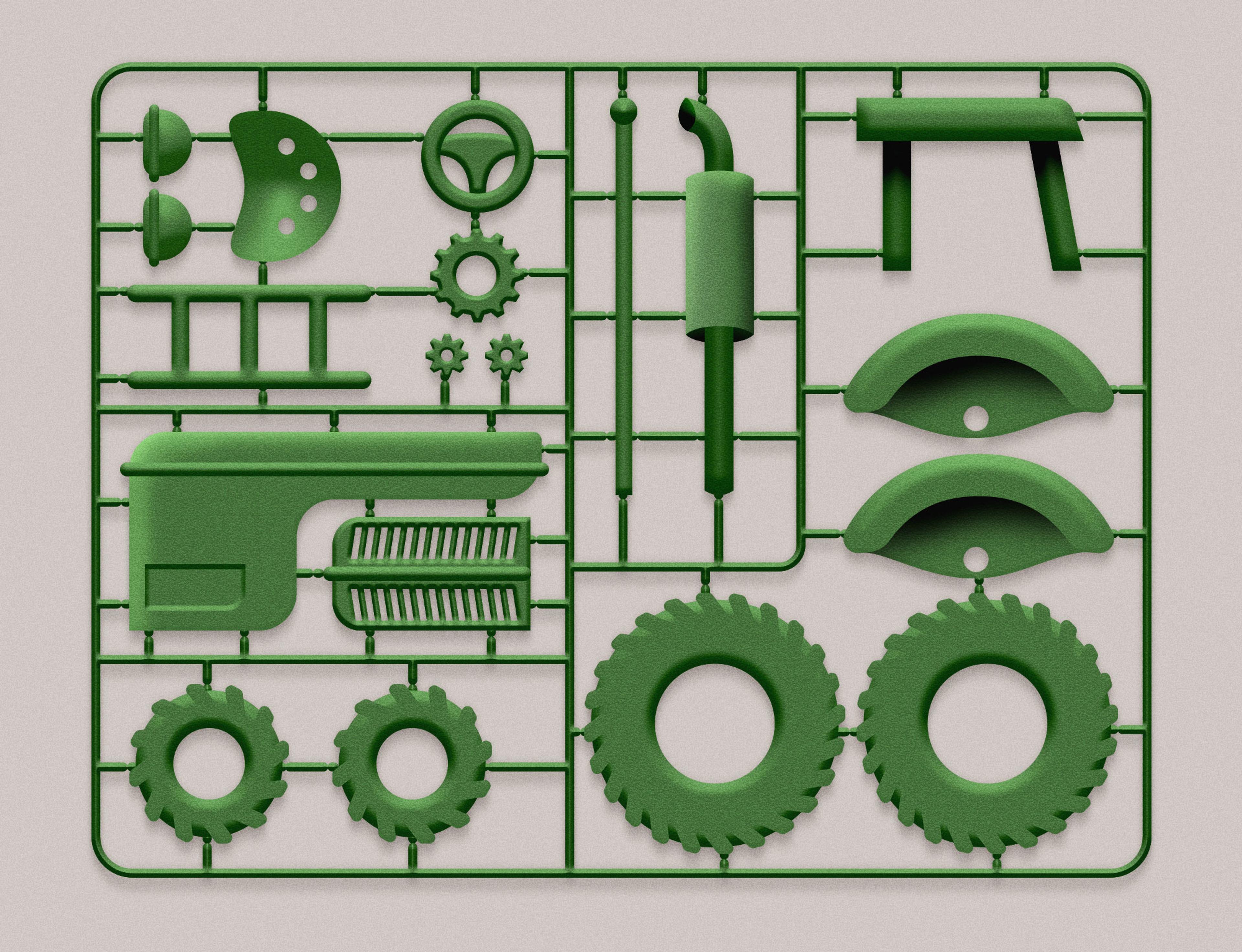

For the small to midsize grower, particularly diversified farmers who grow an array of food crops, investing in expensive, massive equipment for a single crop isn’t feasible. Many midsize growers still employ decades-old machinery, or import specialty equipment from overseas.

Used equipment gets the job done, but if it breaks down, tracking down replacement parts can be a headache. Repairing the equipment might be the only option, too, as full replacements are unavailable or prohibitively expensive.

For instance, no American manufacturer produces a single row corn picker today. New Idea, a now-defunct farm equipment company, manufactured a single row corn picker for much of the 20th century, some of which are still available from secondhand dealers. One of the company’s original models, manufactured in 1952, is housed in the collection of the National Museum of American History.

“Ag is constrained in large part by the land that you own and the labor that you have,” said Trey Malone, an agri-food economist at Purdue University. “And so if I have a larger planter or harvester, then I can manage more acres myself without having to have somebody else.” While large equipment is readily available for farmers growing commodity crops like corn and soy, tracking down equipment for vegetable crops is less straightforward. Meanwhile manufacturers like John Deere are implementing new technology like artificial intelligence which drives up the overall cost of their products.

”The large producers are going to have to make those investments or are going to be able to make those investments in a way that the mid-sized players will not be able to because they just don’t have the money,” said Malone.

Many organic farmers who grow a diverse array of crops, like Peter Seely of Springdale Farm in Wisconsin, still employ the trusty Allis Chalmers G tractor, which was manufactured from 1948 to 1955. Even 70 years after its production run, the G tractor remains popular with small vegetable farmers. “All the vegetable growers really love them. It has a small 10-horsepower engine on the back and then in the front you can hang a cultivator, or a seeder, or other things, and you can see clearly what you’re doing,” said Seely, who grows everything from leeks to cantaloupes to zucchini.

“Ag is constrained in large part by the land that you own and the labor that you have.”

Multiple startups have attempted to recreate the G tractor, although none of them have yet seen lasting success.

Vegetable harvesting equipment, particularly for midsize farm operations, is a niche market. Seely has purchased specialty equipment from Europe and Japan, including a leek harvester from ASA-LIFT, a Danish manufacturer. Investing in harvesting equipment for a single crop means Seely has to grow enough of the crop each year to make the investment worth the money. He says having five to 10 acres of a single crop is the starting point to even consider investing in harvesting equipment.

Meanwhile brand-new combine harvesters run well into the six figures. John Deere’s top-of-the-line models will set you back over $800,000, and even 10-year-old models on the secondary market can still fetch over $100,000. Some of John Deere’s old combines, like the John Deere 55, look like children’s toys next to contemporary behemoths.

Lettuce is another headache for the midsize grower. “Most of us that grow lettuce mix on a smaller scale, you have these little hand scissors or something a little bit more efficient than that, but there’s not too many things in between for a grower that would have two to five acres of it,” said Seely.

Seely is currently in the process of purchasing a speed disc from Maschio, an Italian company. John Deere manufactures speed discs as well, but they’re too expensive and too large for Seely’s operation.

Ryan Pesch, a farmer and extension educator at the University of Minnesota, encourages new farmers to scale up slowly in crop production and have an established base for their product before they invest in specialized equipment. ”It just takes a while for folks to build a customer base, even if they’re putting out good product,” said Pesch. Buying specialized equipment — Pesch used the example of a carrot harvester and buncher — means a farmer needs to have several years of production and sales experience at a smaller scale before investing in such equipment.

Some new American producers and importers have entered the market in recent years, like Small Farm Works and Neversink Farms, both of whom sell a version of the paper chain pot transplanter system, a revolutionary way for midsize farms to quickly transplant crops. The system works by loading a tray of seedlings into a metal chute, which transplant the seedlings as the device is dragged across the soil. Seely, who uses the system, said it has dramatically cut down on the time it takes to transplant crops and reduces stress on the body from kneeling and bending over when planting crops.

”The large producers are going to have to make those investments or are going to be able to make those investments in a way that the mid-sized players will not be able to.”

”This has been a game changer for a lot of small farms because you can transplant five times as quick, so you’re saving a lot of labor costs,” said Seely. The paper chain pot system — a Japanese invention — was brought to the United States in 2006 after John Hendrickson, a Wisconsin farmer, learned about it while living in Japan for a year.

Simon Yevzelman of Cedar Field Farms in Belleville, Michigan, runs a market garden-style farm on a half acre of land. Many of his tools are from Neversink, a producer of tools for the market-garden farmer, which Yevzelman favors for their quality. “ I couldn’t wait for the one that was coming in the mail from Neversink, so I bought one from the local hardware store, and it was just the worst junk,” he said. “I’m going to go for the tools that are manufactured specifically with [market-garden] in mind.”

Bryce Loewen, who runs Blossom Bluff Orchards in California, relies on a mix of used and new equipment, but usually only turns to purchasing new items when he has grant funding available. Loewen recently purchased a new tractor with the help of a California subsidy program that helps farmers trade in old tractors for newer, more environmentally friendly ones.

Loewen, who takes pride in producing high-quality stone fruit, lets his peaches, apricots, nectarines, and plums ripen on the tree to deliver them to consumers in a pristine, ready-to-eat state. Working with delicate fruit during the harvesting process means all the fruit on Loewen’s farm is harvested by hand, a process no machine can replicate. Chez Panisse, the famed farm-to-table restaurant in Berkeley, California, is among Blossom Bluff’s customers.

While Loewen is usually able to get his hands on the right equipment, he ran into some roadblocks when attempting to acquire a new bush hog mower. His local dealer didn’t have any mowers in stock, so Loewen put himself on the waitlist, but the dealer never called him back, prompting Loewen to purchase a used unit instead. “ I felt a little brushed off, and it seems like if we’re not buying multiple units like the big guys do, there’s less interest in following up and selling a single mower instead of 10 or 15,” said Loewen.