New England farmers are participating in the first known field trials of human-urine fertilizer in the U.S.

Twice a growing season, a big yellow truck with the license plate “P4FARMS” pulls into Jesse Kayan’s farm in Brattleboro, Vermont, loaded with a thousand gallons of pasteurized human urine sloshing around in IBC totes.

For more than 10 years, Kayan has been applying human urine to his hayfields through a partnership with the Brattleboro-based Rich Earth Institute, a non-profit engaging in research, education and technological innovation to advance the use of human waste as a resource. In August, Rich Earth released a Farmer Guide to Fertilizing with Urine, available for free on their website. The guide compiles a wealth of information and best practices based on working with farm partners like Kayan and a growing body of scientific research from around the world.

“Our hay yields have gone way up as a result [of the urine],” said Kayan. “We have really hungry land and sandy soil. It’s brought it up to a new level and provided some resiliency in the soil health.”

Kayan, whose business relies on the organic vegetables he grows for his farmstand and CSA, said he’d be happy to use urine on other crops if the practice was more widely accepted by consumers.

“I personally, if it were my garden I would not think twice about it,“ he said. ”I really don’t think there’s actually any food safety concerns. It’s a matter of perception.”

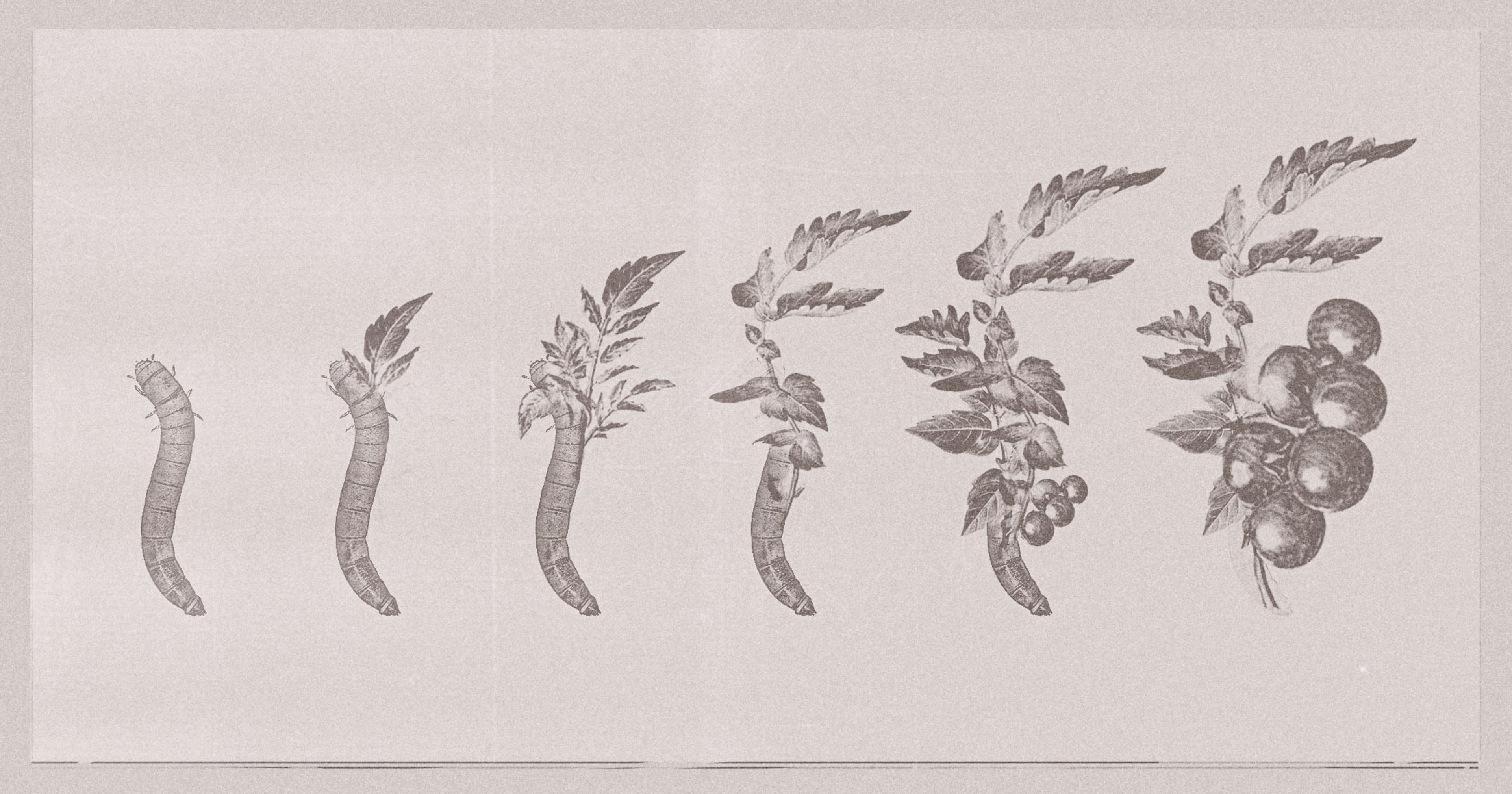

Kayan is one of nine Vermont farmers who’ve participated in Rich Earth’s field studies, funded by USDA Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE). In addition to hay, Rich Earth has conducted trials on sweet corn, hemp, figs, nursery trees, and cut flowers. The multi-year trials found that crops fertilized with human urine performed better than untreated control plots.

Kayan and other farm partners also observed higher yields and/or more robust growth and color in the urine-treated plots relative to those treated with conventional synthetic fertilizer; however, the trials found no statistically significant difference in total yields or relative feed value. That said, some international studies have shown improved yields and growth in certain urine-fertilized crops, such as cabbage, maize, and cucumber.

This is no surprise to Arthur Davis, who oversees farm partnerships for Rich Earth. He said human urine has a nutrient profile similar to many commercial fertilizers, with high levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, as well as micronutrients like magnesium, sulfur, and calcium.

But the potential benefits of fertilizing with human urine reach far beyond the fields of Vermont. Most commercially available fertilizers rely on synthetic nitrogen produced through the Haber-Bosch process, which accounts for 1.4% of carbon dioxide emissions, and 1% of total global energy consumption, according to the journal Nature Catalyst.

Most of this energy comes from natural gas, which means that the price of fertilizer is closely tied to the price of natural gas, a cost that is passed down to farmers and consumers. But the carbon footprint of conventional fertilizer doesn’t stop there. Mining of phosphate and potash are depleting natural reserves. The Global Phosphorus Research Initiative predicts a shortage of rock phosphate within the next 40 years.

“Our hay yields have gone way up as a result [of the urine].”

Diverting urine from the wastewater stream for use as fertilizer would also address the two largest contributors of nutrient pollution in the U.S., agriculture and human waste, which are responsible for toxic algae blooms, aquatic dead zones, and a wide range of human health conditions. It could also reduce nitrous oxide emission by keeping urine out of uncovered waste lagoons, where it festers with methane-breeding solid waste. Not only that, but urine-diverting toilets — available through Rich Earth — require little or no water to flush, which by their estimates could save up to 900 billion gallons of water per year in the U.S. Some of this water can be recycled for use in irrigation.

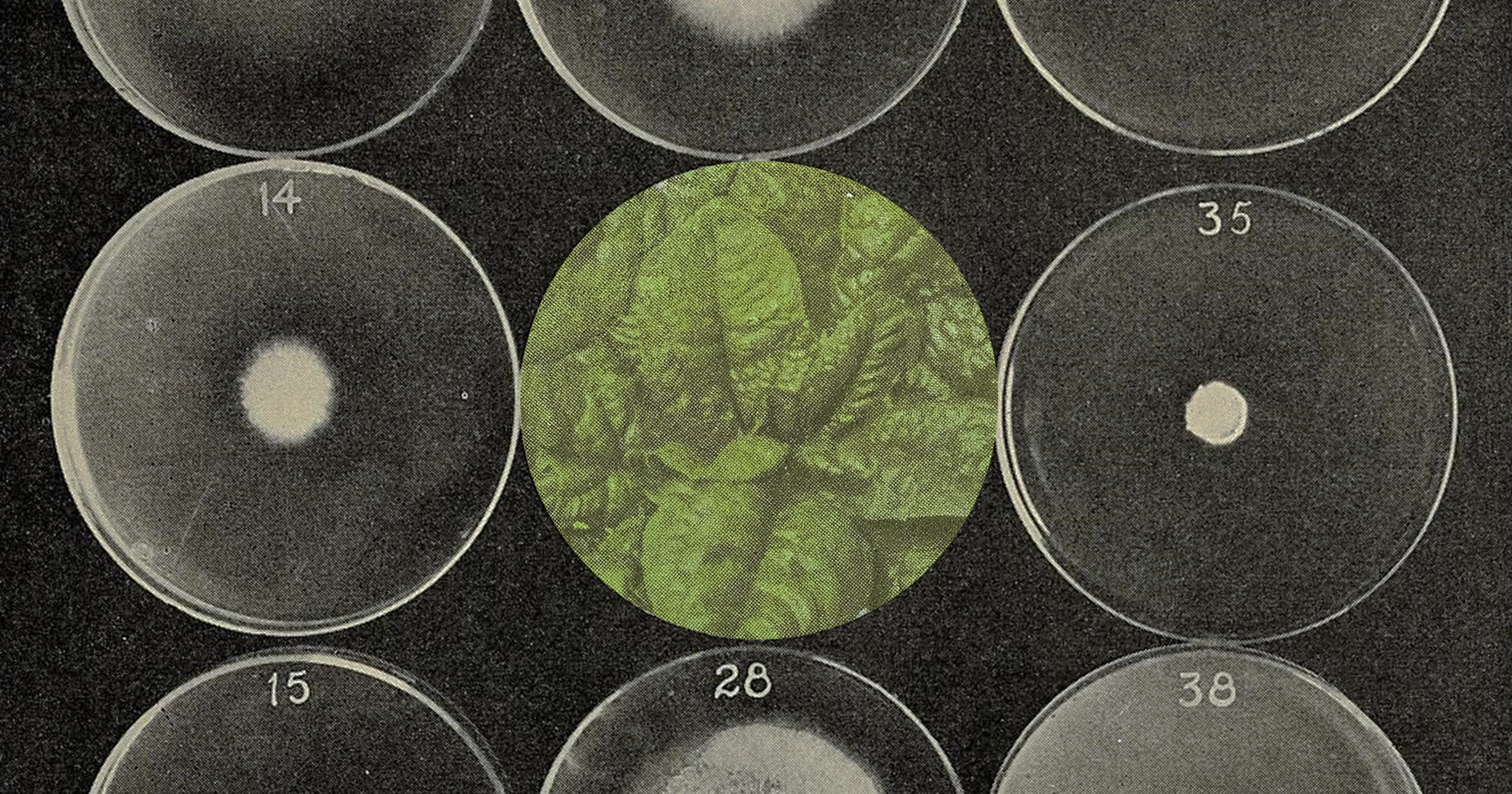

Initially, there were concerns about trace levels of pharmaceuticals in urine, but a recently concluded study by Rich Earth in partnership University of Michigan, the University at Buffalo, and the Hampton Roads Sanitation District in Virginia, detected no significant buildup in crop tissues. Davis said they are now also testing for PFAS; so far their samples have tested negative or extremely low.

If human urine is a safe, cost-effective and environmentally sustainable alternative to conventional fertilizers, why hasn’t it already been adopted on a larger scale?

One fundamental challenge of fertilizing with human urine is ammonia volatilization, which can cause the nitrogen in urea to evaporate quickly during storage and application. To prevent this, urine is applied as close to the ground as possible, and incorporated into the soil immediately.

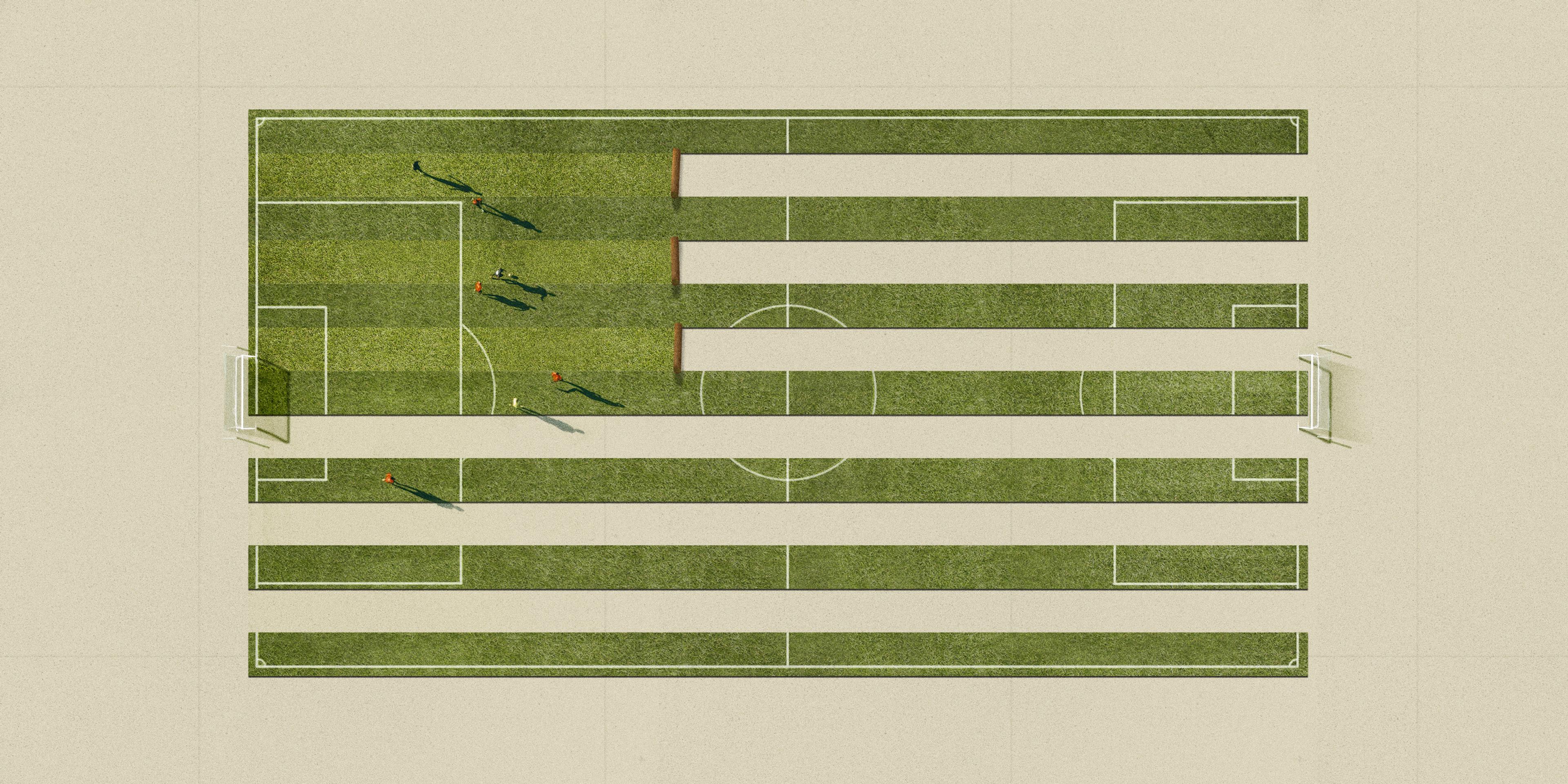

Davis has worked with farm partners to develop application methods that are both practical and effective. For Kayan’s hay fields, Rich Earth uses a custom-built, 500-gallon trailer tank attached to a 30-foot boom suspended about three feet above the ground. The urine drizzles out evenly through small holes spaced every six inches.

“It’s incredibly easy,” said Kayan. “It requires basically just one person on the farm and some sort of form of locomotion.” In his case, this means a team of Suffolk Punch draft horses, but the same apparatus can be hitched to a tractor. “It’s real fast and easy, you can fertilize a lot of land real real quick with it.”

“When you’re filling the bulk tanks to go out and spray it’s really really powerful, but when I’m applying it I don’t really smell it that much.”

John Janiszyn, who runs a multigenerational farm stand in Walpole, New Hampshire, has been using urine on sweet corn for several years, and this year is testing it on his pumpkins.

Davis helped him modify his tractor so that he could cultivate his fields and apply urine in one pass. The urine flows from a tank attached to the three point hitch down through a hose onto the ground, where it is immediately buried by his cultivator. For his pumpkins, they applied the urine under a layer of plastic mulch, trapping the nutrients in the ground.

For Janiszyn, one drawback of using urine is that it is highly diluted. “You need a lot of it to do an acre,” he said. “So you sidedress or whatever and then have to go back and refill and keep going.”

It takes about 1000 gallons of urine just to fertilize one acre of hay. Currently, Rich Earth is nowhere close to being able to meet that kind of demand.

Rich Earth sources its urine from about 250 donors in the Brattleboro area, the first and largest ever community-scale urine nutrient reclamation project in the United States. At their central treatment and storage facility, the urine — about 12,000 gallon a year — is sanitized using a computer-controlled pasteurizer.

“I think it’s a little bit of a chicken and the egg,” said Davis. “It requires farmers to really feel like it’s worth investing in new equipment. They want to feel like they have steady access to the material in the first place, which then requires, on the backend, systems in place for collection and treatment.”

In Vermont, Rich Earth has been working with lawmakers for over a decade to clear regulatory pathways, and are now beginning the process in Massachusetts and New York.

“It’s purely the optics that I would worry about, and I really think that that’s just a matter of time [until it becomes normalized].”

“We’re probably the most kind of far along group in this country in terms of having a whole ecosystem of collection, treatment, transport, application, all under one regulated program,” said Davis.

Rich Earth offers assistance to organizations across the U.S. to obtain approval for farm-scale urine application, including the Land Institute of Kansas, which launched its own urine reclamation project in 2023.

But the greatest obstacle to making peecycling mainstream may not be logistic or regulatory at all. It goes back to what Kayan said about public perception.

“It’s purely the optics that I would worry about, and I really think that that’s just a matter of time [until it becomes normalized].”

“I don’t really want to be the first one,” he added.

Janiszyn and his wife Teresa found out about Rich Earth when they participated in one of their focus groups examining public attitudes toward urine reclamation.

“It was funny how having us in that focus group sort of changed people,” he said. “We said we use cow manure and stuff and this [urine] doesn’t sound like it would be an issue. And I remember one guy was like, yeah, well, hearing from these guys, you know, I guess it’s not that bad.”

Janiszyn said that after his experience in the focus group he wasn’t too concerned about customer response. “I realized that if I’m positive about it people will just come along with it. You have to have some control over the narrative.”