Bugs could connect the ends of the food system by eating waste and creating fertilizer. But the industry will take time to hatch, experts say.

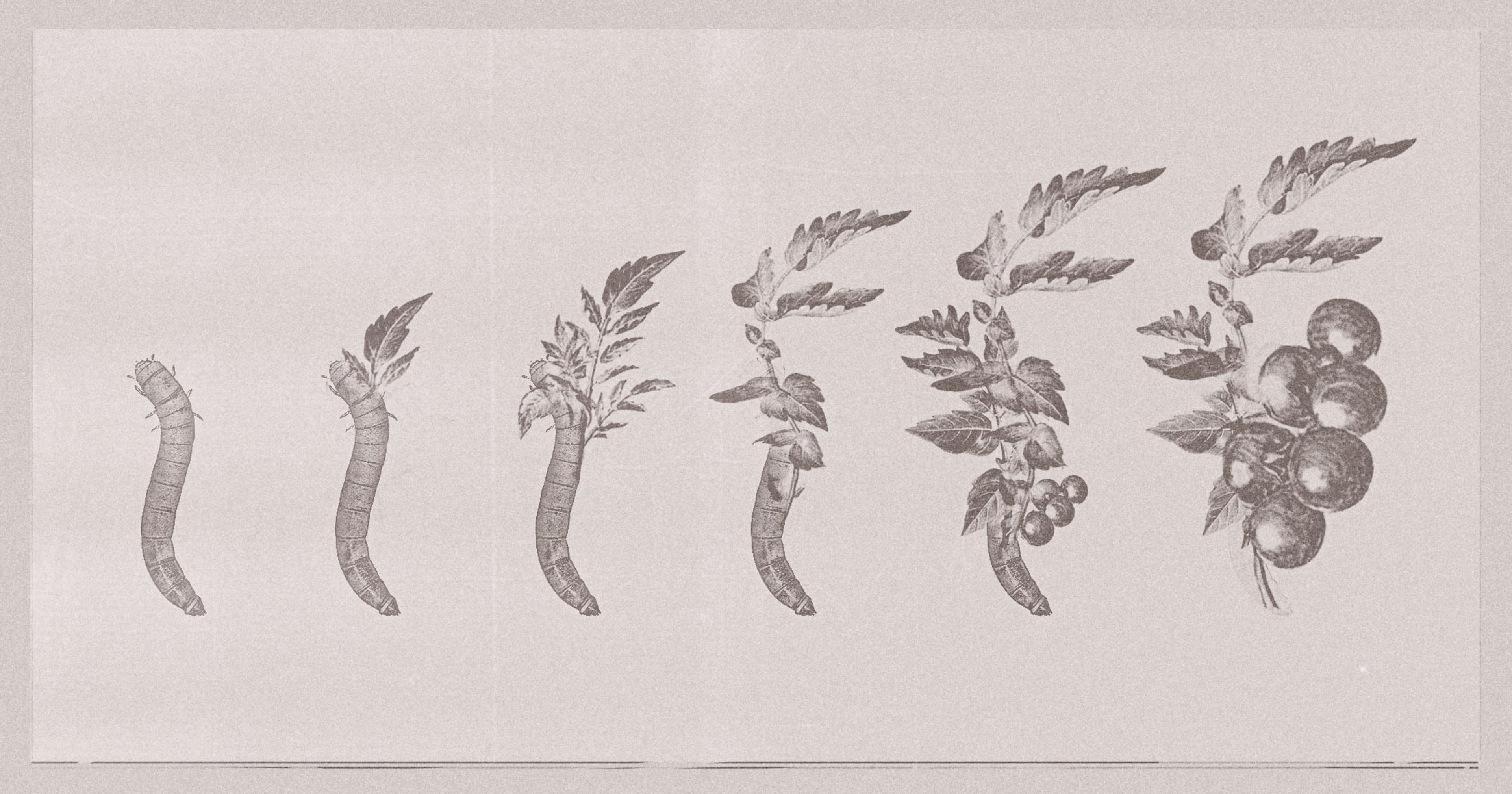

We throw out approximately 30 to 40 percent of all the food grown in the U.S. Insects, meanwhile, are happy to munch on our food waste. In turn, their waste can fertilize the soils that grow tomorrow’s tomatoes.

This idea — that insects can round the circle of our food supply system — has gone from a dubious proposition to a valued addition in the agriculture community over the last decade.

A recently published, federally funded two-year field study in Arkansas sought to stack insect poop, called frass, against the standard ammonium nitrate fertilizer. Frass, the study found, increased the key elements that make soil fertile for crops as compared to nitrogen-based fertilizer. It also enriched the soil more than another common organic fertilizer, poultry litter — a mixture of chicken manure, pine wood shavings, and spilled feed.

That’s the beauty of insects, said USDA soil scientist Amanda Ashworth who led the study alongside colleagues at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville, Arkansas.

“They can pretty much eat anything and turn it into some really value-added products — so I think it’s really exciting,” Ashworth said.

A Bug’s Life

Like all livestock, mealworms poop. But unlike their warm-blooded peers, a mealworm’s poop is nearly odorless, with subtle hints of vanilla. That’s according to Cheryl Powers, who co-founded and manages the commercial mealworm farming company Kirkos LLC.

Kirkos‘ mealworm manure — golden in color, sandy in texture — is produced within a warehouse in the suburbs of Omaha, Nebraska. There, millions and millions of yellow mealworms munch on wheat bran, carrots, and potatoes within plastic tubs stacked high in the facility. The worms grow to around one and a quarter inch in length before being shipped to wild bird businesses and exotic pet markets, Powers said.

The golden color of the frass reflects their potato-heavy diet — when the mealworms eat a more carrot-heavy diet, their frass turned more orange, Powers said.

Frass is sold by the bagful to farmers looking for a chemical-free fertilizer. Under the mantra of nothing going to waste, Kirkos also sells frass that cannot be separated from exoskeletons and leftover food scraps to local farmers. (The mealworms, like many kids, don’t like potato skins, Powers said.) That waste heads for the farmers’ compost pile and eventually spreads across fields or mixes into potting soil.

Frass enriched the soil with higher concentrations of carbon, nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium compared to ammonium nitrate, the study found.

In addition to a well-balanced N-P-K value, Powers said that her company’s frass is safe to spread across fields of fresh vegetables. It tests negative for common bacteria including Salmonella, Listeria, and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli. It is also clean of seeds from weeds that find their way into cow manure and end up sprouting amidst the crops that the manure is meant to fertilize.

But the unique sandy nature of frass is also its primary downside, Powers said. It is difficult to spread on a field, she has heard from farmers, because it blows away. While frass could be compacted into pellets, the heat of that process would degrade some of the microbes that make it appealing as a fertilizer — a Catch-22, according to Powers.

Local Fertilizer

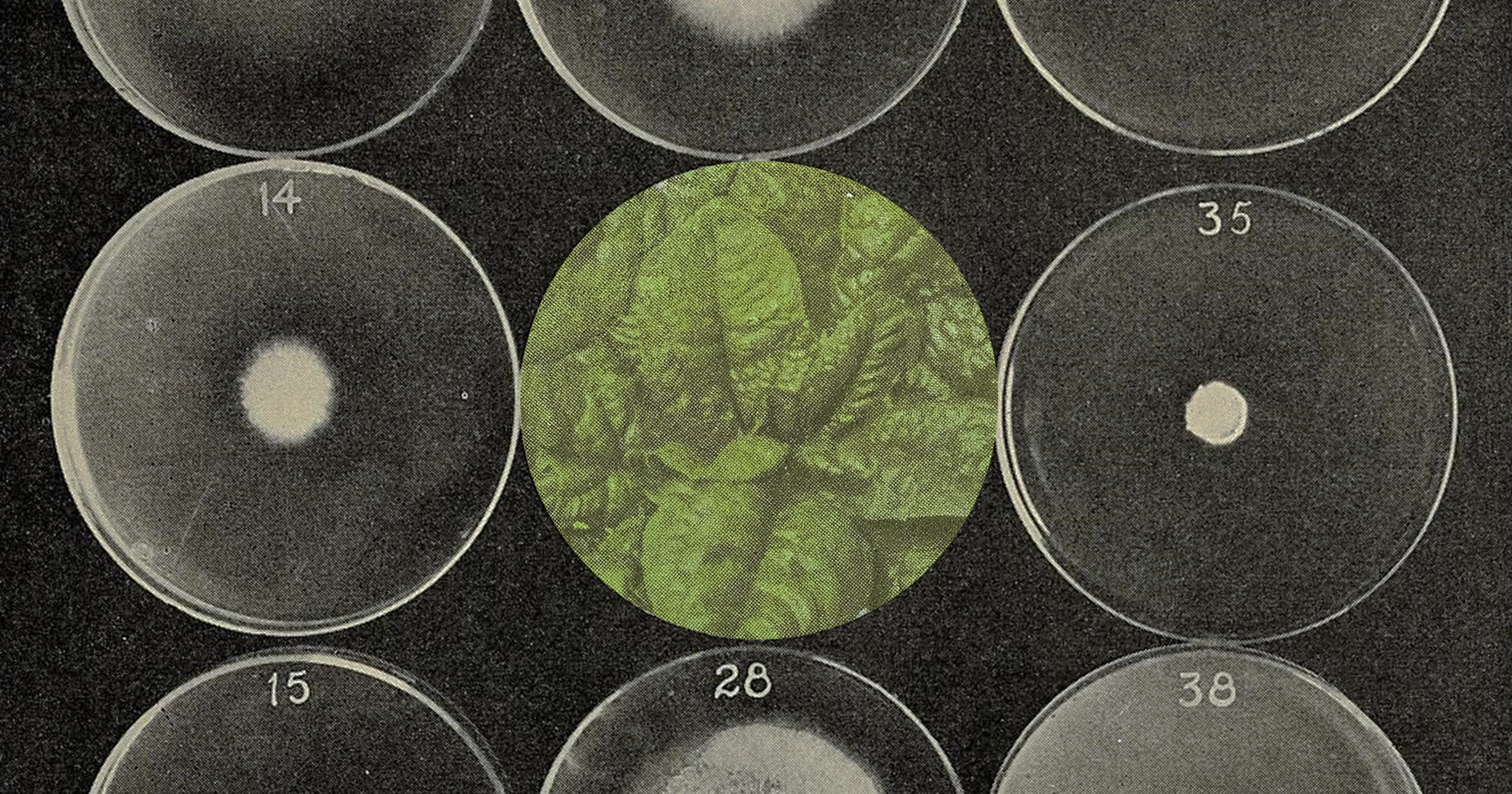

Mealworm frass was compared to poultry litter and ammonium nitrate on the fields of the University of Arkansas research station in Fayetteville. Fifteen plots of land received one of the three fertilizers — frass and litter being the organic fertilizers; ammonium nitrate, the standard fertilizer — and five plots received no fertilizer.

For two years, Ashworth and her colleagues pushed cylindrical probes into the soil, by hand, pulling out cores of dirt. Soil was tested for nutrients and elements in the lab.

Frass enriched the soil with higher concentrations of carbon, nitrogen, potassium, phosphorus, and magnesium compared to ammonium nitrate, the study found. Frass fertilized soil also had higher levels of nitrogen, potassium, and magnesium compared to poultry litter, while the carbon and phosphorus levels were similar between the two organic fertilizers.

The nitrogen enrichment was particularly exciting for Ashworth, she said, because of the high nitrogen fertilizer prices facing farmers these last few years. Prices are likely to spike again with the added tariffs imposed by President Trump’s administration on imports from Canada including fertilizer and fertilizer ingredients.

Mealworms in their study received “the primo diets” of wheat bran and potatoes.

“If we could find a local source of nitrogen for crops, that would be huge,” she said.

Ashworth noted that the mealworms in their study received “the primo diets” of wheat bran and potatoes. Their poop, as expected, “is going to be more primo,” she added.

Commercial insect-rearing companies, in contrast, may not use such high-quality foods. Bacteria lurking in lower quality insect food transferred to the frass in another study by Ashworth and her colleagues.

This poses a potential health risk, Ashworth said. “You don’t wanna put pathogen manure out on lettuce, right?” Composting is one straightforward solution to this problem. Heat kills the pathogens, making the frass safe for fields.

The limitation of frass fertilizer — the reason that not all farmers are sprinkling frass across their fields — is that there just isn’t much frass being produced. “It’s a huge growing industry,” Ashworth said. “There’s a lot of startups with insect agriculture and, because it’s a new area, there’s still a lot of unknowns and things to be worked out in the supply chain.”

Treasured Trash

The insect agriculture industry of today coalesced from two disparate groups: edible insect enthusiasts and old-timers in the live bait market, said Aaron Hobbs, executive director of the North American Coalition for Insect Agriculture trade group.

The first conference in the U.S. on entomophagy, the process of eating insects, was held in Detroit, Michigan, in 2016. Since then, the industry has matured to focus not just on insects as food — whether humans or other animals — but on something called bioconversion, he said.

“It’s taking things that are fairly low value for other uses — insects are happy to consume it, and then creating products that are valuable for people and the planet,” Hobbs said. The industry’s trade group incorporated in 2019.

In other words, insect agriculturalists now unite under the old adage, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.”

One of these treasures is insect-derived fertilizer and soil amendments, Hobbs said. Overall, he said the insect ag industry growth has been slow but steady. “The industry as a whole has learned a lot from each other and from experience about how to properly size and and run these facilities,” he added.

The insect agriculture industry of today coalesced from two disparate groups: edible insect enthusiasts and old-timers in the live bait market.

U.S. fertilizer regulation is a headache for small frass companies and big nitrogen fertilizer companies, alike, Hobbs said. Each state has its own registration process, and although some states coordinate their specs, each single product with the same N-P-K values may need at least four registrations to sell across the country.

While insect frass cannot currently meet the demand for fertilizer in the U.S., the federal government recently invested millions in two insect ag companies, awarding $11 million to Innovafeed and $4.6 million to Chapul Farms, in order to pilot insect-to-fertilizer projects.

But the industry has also had its growing pains. Two large-scale insect farming companies, Ÿnsect and Agronutris, have sought financial shelter from French courts in the last year as they raised funds and worked to pay off debts. No investors came to Ÿnsect’s rescue and the company entered judicial recovery procedure in February.

Hobbs expects that much of the industry’s future growth will be through partnerships with grocery store waste companies, packaged food processors, and large food producers. In 2023, for instance, Tyson announced a partnership with the Dutch insect ingredient company Protix to build a facility in the U.S. that will feed food manufacturing byproducts to insects. The next year, in April 2024, food processor heavyweight Archer-Daniels-Midland opened a pilot plant of black soldier flies with French insect protein company Innovafeed in Decatur, Illinois.

Studies like Ashworth’s are necessary steps towards understanding “the real awesomeness of frass,” Hobbs said.