Scientists have discovered significant effectiveness of bats for orchard pests. But the nighttime hunters are fickle about where they settle down.

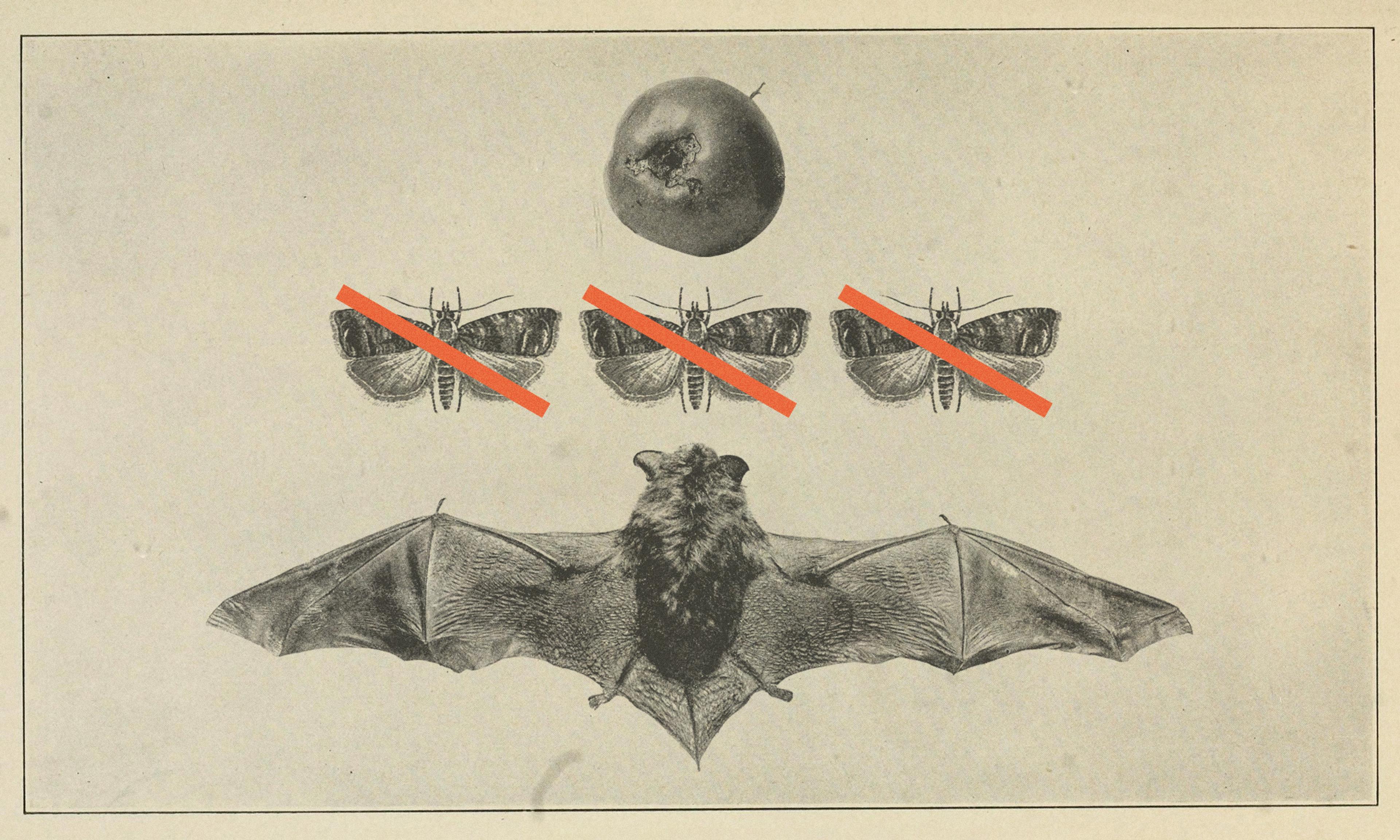

With its bark-patterned, brown wings, the codling moth looks innocuous as it flutters around fruit and nut orchards. But this seemingly innocent little insect is responsible for boundless destruction to orchards around the world.

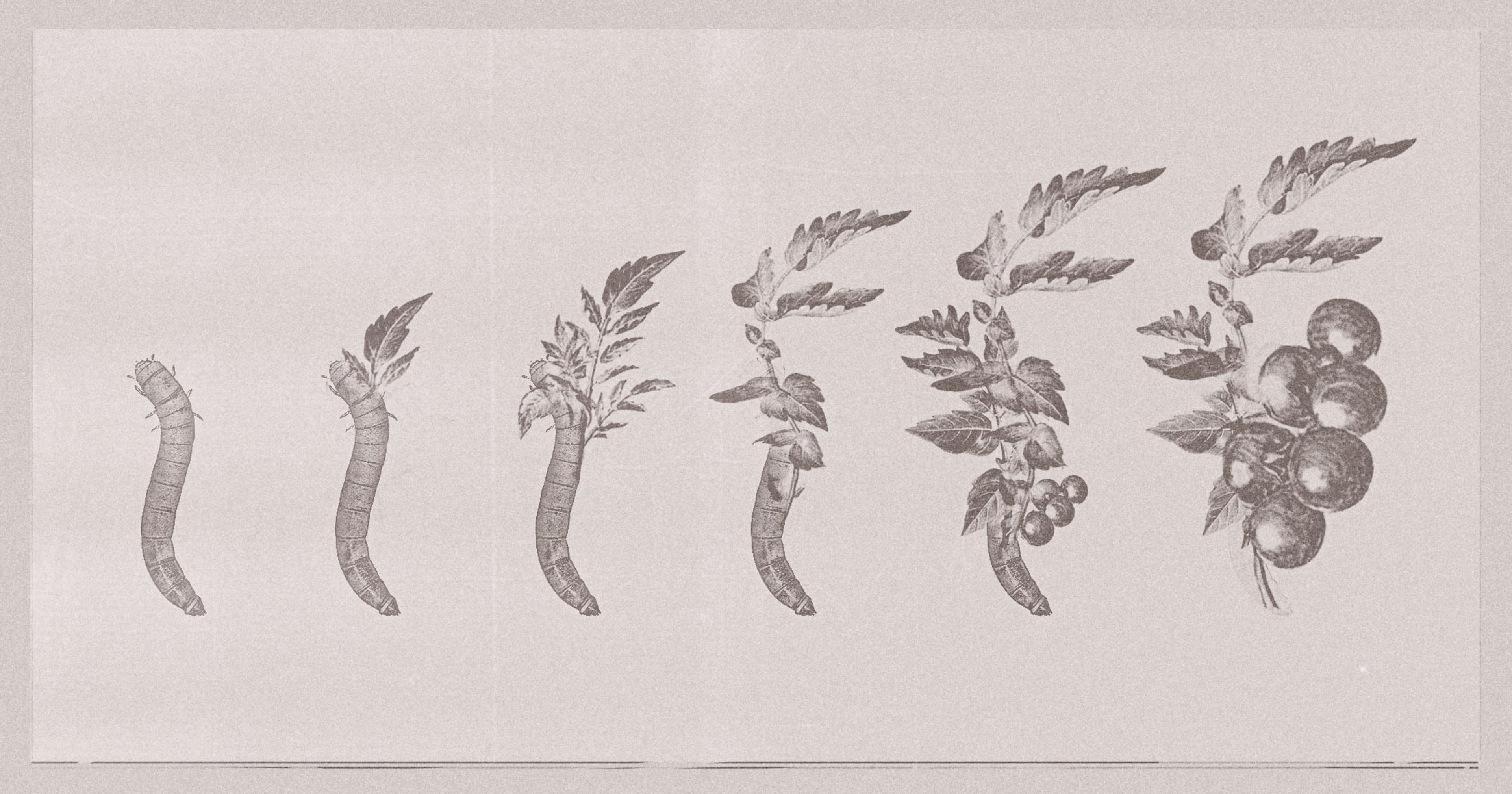

For codling moth caterpillars do not survive by munching on leaves. Instead, they head straight for the fruit. Once there, they burrow into the flesh, sealing the hole behind it. The burrowing takes less than an hour, but results in an unpleasant surprise: The apple now has a wormy guest, all but ruining its appeal for eaters.

Orchards can experience multiple generations of codling moth hatches in a season. And if farmers leave the pests uncontrolled, they can wipe out an entire crop.

Trying to control the moth takes a big investment of time and money. In apple orchards, it is estimated that 70% of insecticides are used to combat codling moths. But the pest is wiley — it’s been described as “plastic” in its adaptation to pesticides. Case in point: In the 1980s and 90s, orchards in Europe controlled the codling moth with broad-spectrum insecticides, only to be foiled as the moth developed a resistance to the chemicals.

Growers try a gamut of pest control measures, including insecticides, pheromone disruptors, putting nets on developing fruit, and introducing beneficial insects. But one management approach has shown particular promise tamping down the ubiquitous codling moth: bats.

The flying mammals are dynamic and voracious feeders, sometimes consuming thousands of insects in a single night. A lactating female bat can eat 150% of her body weight in insects per day, said Danilo Russo, an animal ecologist at Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II in Italy. Multiply the number of bats in a colony by the number of insects eaten, and you get an efficient insect assassin.

But while it is clear that bats provide important pest control services to the world, few have attempted to quantify their impact in cold, hard terms. So Russo and his colleagues headed to an organic apple orchard in Italy to test the efficiency of bats for pest control — including a calculation of the economic benefits of the flying predators. They published their findings in the Journal of Nature Conservation.

Within the orchard, they compared two neighboring areas — one where bats hunted freely and one where bats were excluded with night-time nets. The nets were closed before dusk and opened at dawn, to allow pollinators and other animals to behave as usual during the day. The scientists then collected the apples to compare the amount of damaged fruit in bat-hunted areas to those that were excluded from the flying insectivores.

Photo: Michela Ruberto

·Codling moth larvae burrow into an apple, creating an unappetizing snack for consumers

They found that in the area of the orchard where bats hunted, there was a 32% drop in trees affected by codling moths. In addition, the number of damaged apples was cut by roughly half. Russo said his academic collaborators added an economic layer of information to their findings. “The level of damage can be turned into money, which everyone will understand,” he explained. In total, the presence of bats resulted in an estimated savings of roughly $1,470/acre each year in preventing damaged apples.

The rub? Coaxing bats to set up house near orchards.

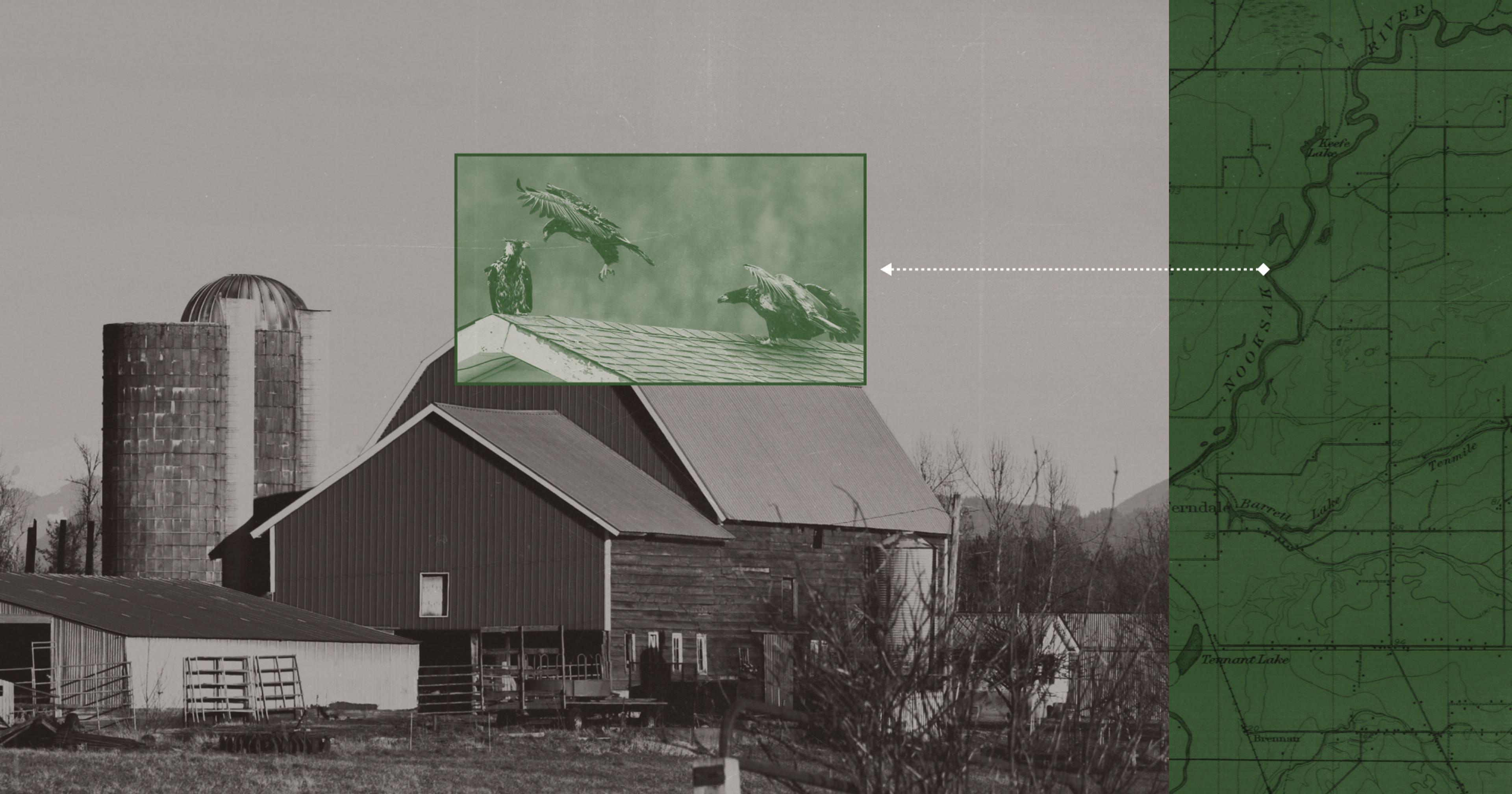

Jim Koan owns Almar Orchards, a 250-acre, multi-generational farm in Flushing, Michigan. A lazy river flows diagonally through the farm, moving through a 100-acre apple orchard, patches of woodlots, and meadows with native flowers and grasses. In the 1980s, Koan transitioned the orchards to organic management techniques, including silvopasture efforts consisting of pigs roaming through the apple trees.

As part of his commitment to eliminating pesticides, Koan looked to natural pest control. In particular, he wanted bats to tackle the codling and oriental fruit moths, which had proven to be difficult to control. “Bats would be perfect because [the moths] are up in the air flying around and mating — and they’re awkward fliers,” he said. “They would be easy targets for the bats.”

Koen believed that on his farm, the biodiversity, available water sources, and presence of an old barn would create a bat paradise. In a Field of Dreams moment, Koen built a couple of boxes — what he called “bat condos” — to attract bats to his farm. He planned to use bats in addition to his other pest control measures like pheromone mating disruptors (an expensive endeavor, both in terms of money and worker-hours).

He said he “did everything that science said you should be doing,” and yet, no bats settled in the condos. His hopes for the bats being an effective pest control method were dashed. Although there were some bats nearby, he couldn’t coax the populations to increase. He concluded that at his farm, “bats are not dependable predators to significantly control those two major apple orchard pests.”

“A lot of bats are just like, ‘This is not good, I’m not resting there — it’s too cold, it’s facing the wrong way, it’s too small.’”

In Italy, the bats seemed to have already set up house near the orchards and didn’t need any coaxing to settle into the neighborhood. “We didn’t find any roosts,” said Russo, but he suspected the bats were nearby. “We mostly found generalist species, such as pipistrelle,” he said, adding that these bats “are not very big fliers.”

Russo reflected on their findings on bat-driven pest control and what bats could mean for other farms and crops. “The kind of information you get from this study may be easily exported to many other situations,” he said. “Although, we worked on a situation which is sort of an ideal paradise with no pesticides, very biodynamically managed. If we tested the same kind of experiment in a more intensive setting, things might be different.”

Joy O’Keefe, a conservation biologist at the University of Illinois agreed, noting that the research was great, but on a small scale. “It was done in one apple orchard in one part of Italy, so it’s difficult to extrapolate out and say that that’s happening everywhere,” O’Keefe said. She added that she’s excited about the work that’s happening with bats and agriculture, and hopes to see more studies that use multiple methods like plant surveys, bat diet discoveries, and behavior of bats in different settings.

O’Keefe added that some bats will adapt to moving into bat boxes instead of natural places, but the conditions have to be just right.

“Not all bat boxes are created equal,” she noted. “A lot of bats are just like, ‘This is not good, I’m not resting there — it’s too cold, it’s facing the wrong way, it’s too small.’” Even old barns, like the one on Koen’s farm, may not be a suitable home for a wary bat. “Maybe the barn looks good, but it doesn’t have enough space or sun, or a snake is living in the barn.”

Photo courtesy of Joy O'Keefe

·Joy O’Keefe poses with a few bat boxes that she is helping install on a farm.

Although farmers can buy pest-controlling critters like ladybugs to eliminate harmful insects, the same cannot be said for bats. “It’s pretty tricky to breed bats in captivity,” explained O’Keefe. In addition, many bats are migratory, traveling long distances. “I don’t know what would happen if you brought bats from captivity and you’d like set them in an area — would they stay or would they naturally want to leave?”

While buying bats and putting up condos may not attract bats to an area, Russo and O’Keefe noted that a more holistic approach might help. “What you can do is try to make a place as bat-friendly as possible,” Russo said. He noted that farmers should integrate lots of diversity into their land, both in terms of crops and land use. “Hedgerows, small ponds, tree lines — all the things that too often are sacrificed [with] intensive agriculture, because in intensive agriculture, you want space, you have mechanization, you don’t want obstacles when you move your machines.”

Farmers have a unique opportunity to help bats thrive — and help control their pests in the process. “Farmers and producers have a lot of power to effect positive change for bats because they do have such vast areas that they control and manage,” O’Keefe said, adding that they have skills and expertise in a variety of land management activities. But as Koen’s struggles show, even skilled farmers might need guidance on how to make bats a regular resident.

Agroforestry practices of incorporating trees into agricultural landscapes can go a long way for farm biodiversity and bat support. Treelines or patches of trees can provide bats with alternate places to forage while different cycles of pests emerge throughout the season. She noted that having a variety of crops supports a more robust bat community, including an extended period of insect control.

Russo agreed, noting that farming could take a look at its history for creating biodiversity and healthy ecosystems. He said the small farms in Italy that existed a couple generations ago were a mosaic of patches of cultivation, forests, and wild spaces, mimicing natural systems rather than large monocultural deserts. “I think we should really spend more energy bringing nature back to agriculture, learning from nature to mimic this spatial and temporal pattern to emphasize the effect of natural lands.”

But even when conditions are great, like on Koan’s organic farm in Michigan, bats can be picky about moving in. “Maybe my situation is a little unique,” he mused. “I had this vision of having bats all over the place in just a few years, but that didn’t happen.”