Fresh produce was a crucial lifeline during my postpartum recovery. The connection between farmers, birth workers, and families can have lasting impact in addressing Black maternal health disparities.

A few years ago, the birth of my second child came hard and fast. Around two weeks postpartum, I experienced excruciating inner thigh pain which cascaded down to my ankle. I thought it was a bad muscle strain. However, doctors confirmed a postpartum blood clot.

With no preparation, and having to separate from my newborn, my six-year-old, and my husband, I was rushed into an emergency thrombectomy. The days, weeks, and months following the surgery were extremely challenging. I was tasked with regaining my strength to walk, and simple duties that many of us take for granted like using the restroom, cooking, or taking a shower were things I had to retrain my body to do — all during the throes of motherhood.

Financially, my family was in a bind, and at first, I hesitated to reach out for help. As a freelancer, I was in no shape to take on assignments and my husband only had two weeks of paid family leave. We drained our savings, utilized need-based grants, and started a GoFundMe for additional postpartum care and necessary medical interventions. All of this occurred during a busy holiday season and I carried the shame of not wanting to be a burden — these days, so many people are struggling.

There was little time to prepare meals and going to the grocery store seemed physically impossible. But I was in desperate need of nutrients to sustain a body still healing from childbirth, nursing and expressing milk, and recovering from surgery.

“The two weeks [postpartum] are critical because while adjusting to parenthood, there is a drastic change in hormones,” said Melan-Smith Francis of Roots Collaborative Care, a Nashville-based midwifery and holistic health organization. “With that, holistic nutritional support is key. Consuming fresh fruit, vegetables, and hydrating with coconut water has the power to heal wombs and give vital sustenance.”

To help ease our worries and aid in recovery, a good friend organized a meal train. Neighbors, friends, and my husband’s co-workers brought crockpot meals, casseroles, gift cards, and various pantry staples. In addition to setting up the train, my friend also delivered a generous yield of fresh fruits and vegetables — collard greens, okra, squashes, apples, corn, and tomatoes — from our nearby community garden.

During a tumultuous postpartum, those around me ensured that I was abundantly nourished. However, it was the fresh food (provided by a micro farmer) that truly made a difference in my recovery. Various studies link low-quality, ultra-processed diets during the postpartum period with adverse consequences.

“Black women in particular are at a higher risk for anemia and postpartum eclampsia,” said Danielle Crumble-Smith, a registered dietitian nutritionist and mother of three. “That’s why fresh, organic, and nutrient-dense produce that has been safely washed and prepared is recommended.”

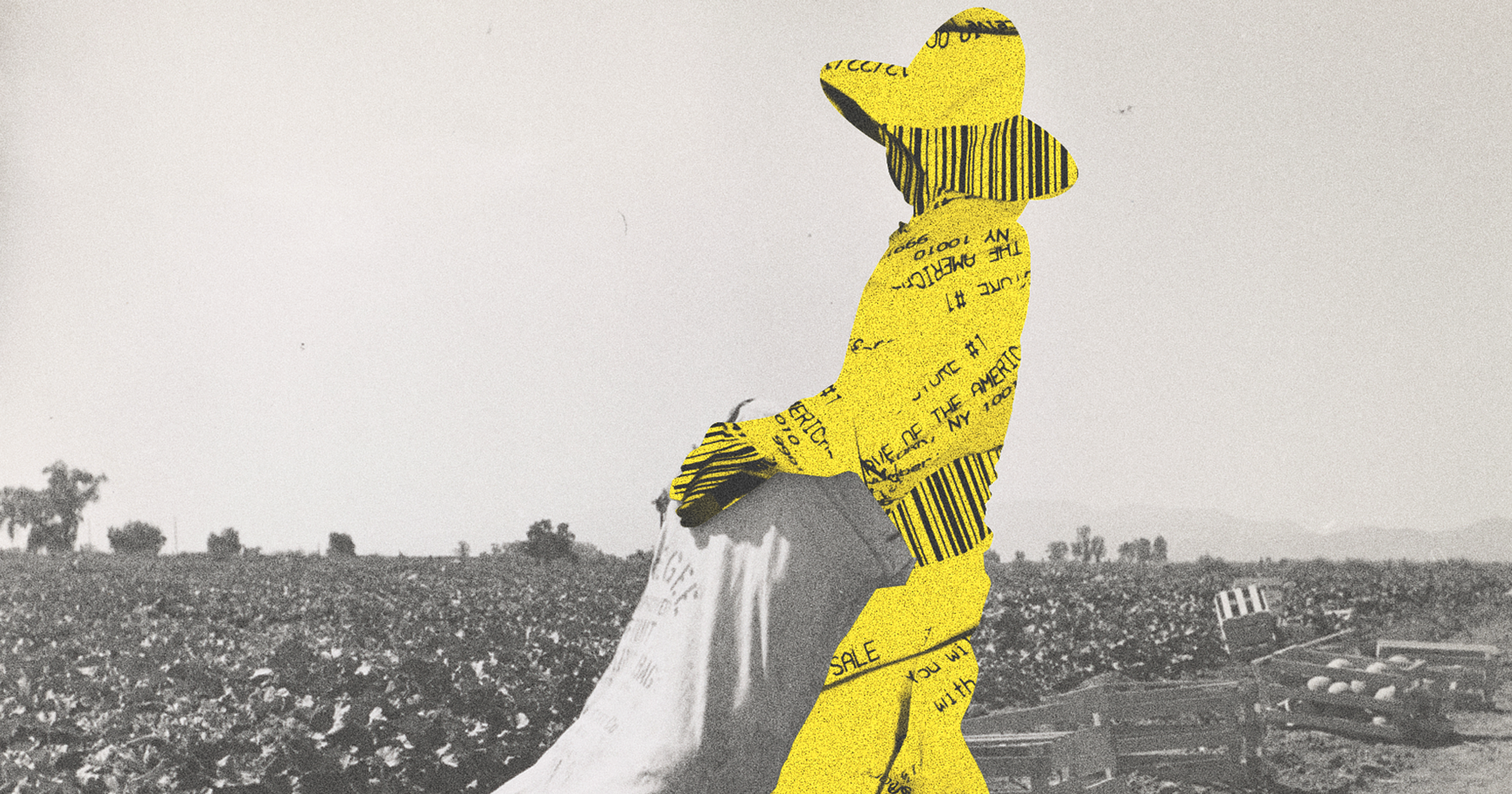

My postpartum story is not an anomaly, and it serves to highlight the subtle yet glaring interconnectedness between farming and maternal health. Uniting farmers, birth workers, and birthing families can provide great value for families — as well as fuel a resurgence of individuals interested in deeply connecting with the land. Moreover, as a Black birthing person, whose likelihood of experiencing postpartum complications is higher than any other demographic, these partnerships can certainly assist in lessening maternal health problems.

Why Fresh Produce Matters

One barrier that some Black birthing people and their families face is access to fresh fruits and vegetables. Food apartheid, inadequate support systems, housing insecurity, and economic hardship remain a systemic challenge.

In Oakland, California, the community group Mothers for Postpartum Justice aims to “share postpartum traditions, expose maternal health inequities, and uphold postpartum justice within the Black community.” Through their Nourish! initiative, postpartum mothers apply to receive healthy meals for up to six weeks for themselves and their families. According to recent activity on the Mothers for Postpartum Justice’s Instagram page, Café 15, a locally owned meal-preparation and catering business, partnered with both organizations to deliver nutritious meals to doorsteps.

While proper nutrition supports optimal health and recovery for birthing individuals, it also helps to honor rooted practices and cultural traditions across the diaspora. The diversity of postpartum foods across cultures supports families and agriculture workers in maintaining their cultural identity during the transition to parenthood.

“Black women, in particular, are at a higher risk for anemia and postpartum eclampsia.”

Across the country in Atlanta, Johane Filemon, nutrition consultant, mother of five, and founder of Wonderfully Nutritious Solutions, credited her own mother with introducing her to fresh, healing produce after the births of her children.

“She fed me fresh folate and vitamin-rich papaya juice in the morning. For lunch and dinner, it would be a plate of Haitian rice and various beans paired with legume, which is a mix of stewed vegetables, consisting of eggplant, tomatoes, bok choy, carrots, cabbage, bell peppers, onions, garlic, parsley, and many other herbs and spices rich in many anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that support my body in the postpartum healing process,” shared Filemon.

Katia Powell-Laurent, founder of Black Girls Nutrition, birth doula, holistic nutrition practitioner, MIT faculty member, and maternal health researcher, believes the community can be a crucial component in ensuring these nutritional needs are met. “Assisting families with connecting them to community resources that help with meal planning, preparation, or delivery can alleviate some of the stressors associated with the early postpartum period, allowing parents to focus more on recovery and bonding with their baby,” she said.

An Urgent Call to Action

If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.

— African proverb

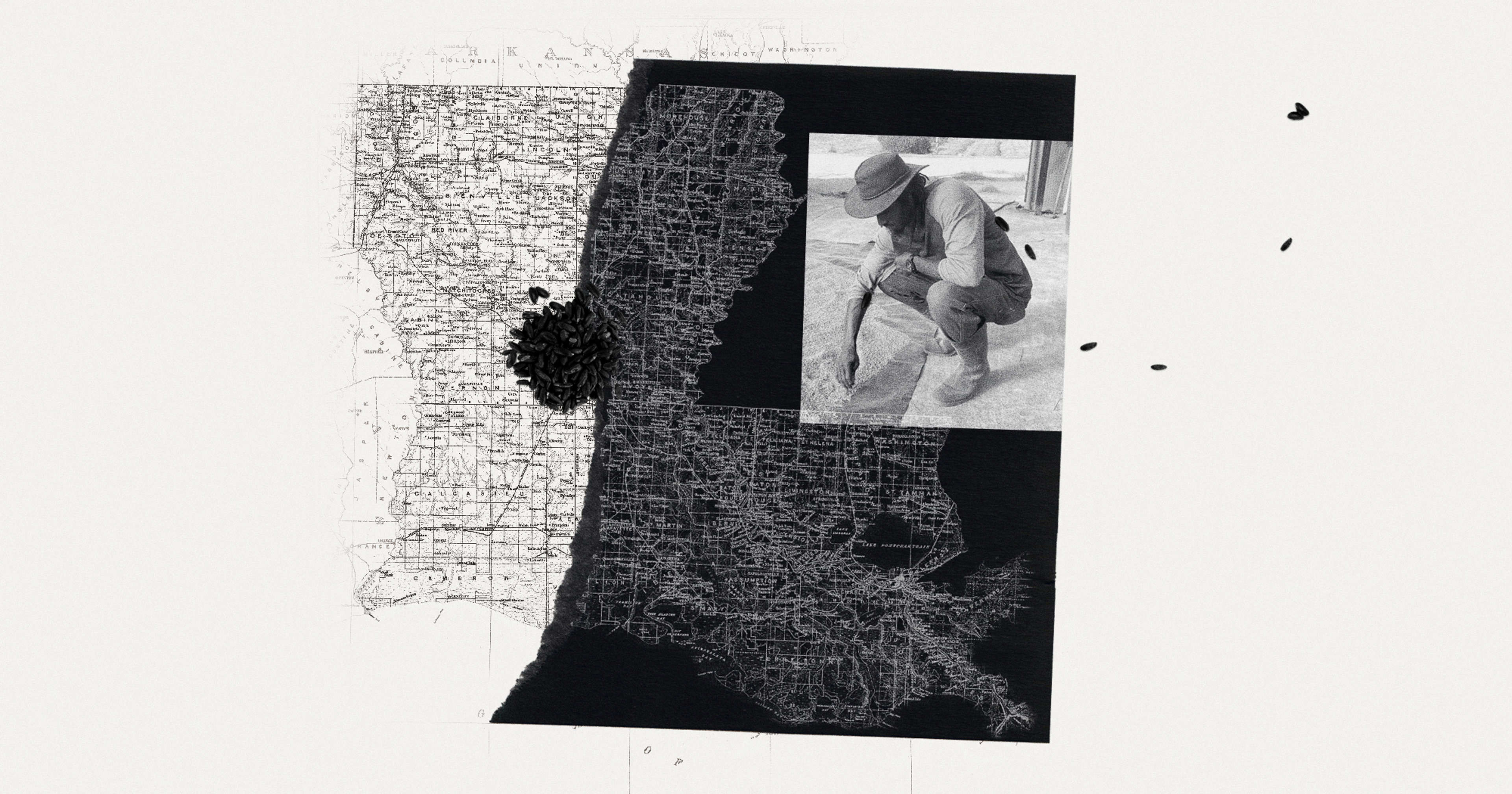

In 2022, Ashley Brailsford, nature educator, mother, and founder of Unearthing Joy, held an annual “Unconference” on her family’s land in Charleston, South Carolina. A gathering of Black women land stewards in the South, this space was instrumental in conjuring ideas in which farmers can help address the Black maternal and infant health crisis.

The women discussed how the development of federal nutritional guidelines, like the food pyramid, has often been influenced more by economic interests than by public health concerns. For example, the promotion of certain food groups has historically been tied to agricultural subsidies and industry lobbying rather than to unbiased health research.

This economic-driven approach can overlook the health needs of diverse populations, including Black Americans, whose traditional diets and nutritional requirements might not align with these generalized guidelines.

“We sat in a circle around a fire and began brainstorming … two major issues that Black and brown birthing people face in the lowcountry is food and housing insecurity,” said Adrienne Troy-Frazier, birth worker, educator, and co-founder of The Bee Collective, a birthing and healing justice organization in Charleston.

“Oftentimes, there’s no place to prepare food — and that’s if there’s enough financial support or transportation to even get fresh fruits and vegetables.”

“Oftentimes, there’s no place to prepare food — and that’s if there’s enough financial support or transportation to even get fresh fruits and vegetables,” Troy-Frazier continued.

Brailsford, who has a farming background, and Stephanie McFadden, childcare and community outreach manager at Fresh Future Farm, came up with a transformational idea at the conference: a two-year pilot program and partnership between The Bee Collective and Fresh Future Farm.

This partnership would allow a small group of birthing people and their families to receive free, daily “heat and eat” meals, along with fruits and vegetables from the farm, available for pickup or to be delivered to those who are physically unable to come to the farm’s grocery store.

Shifting Postpartum Mental Health Outcomes

The link between farmers and postpartum mental health may not be an obvious one, but it is remarkably significant. That’s because, according to the National Library of Medicine, nearly 44 percent of Black birthing people experience postpartum depressive symptoms up to a full year after giving birth — and one of the primary stressors is having access to fresh food.

While struggling with postpartum mental health, I was relieved knowing my six-year-old was fed and that my husband didn’t have to spend so much time out of the house. I grabbed healthy snacks as I made my way to and from doctor’s appointments and therapy sessions — avocados were a lifesaver!

“Trying to figure out what you are going to feed yourself and the rest of your family [if there are older kids], in addition to lack of sleep and not having enough support is a lot to carry,” said Filemon.

Assisting families with community resources that help with meal planning, preparation, or delivery can alleviate some of the stressors associated with the early postpartum period, allowing parents to focus on recovery and bonding with their baby. It also promotes a sense of belonging and collective care, vital for emotional well-being.

“Sharing meals can offer comfort and foster connections among family members and the community. Farmers and birth workers can then encourage practices that involve preparing and sharing meals as a form of emotional support,” said Powell-Laurent.

Since the launch of the pilot program with Fresh Future Farm, Adrienne Troy-Frazier has noticed a significant improvement in the mental health of postpartum mothers who received free meals and produce from the farm.

“We’re reconciling the truth that farmers and birth workers can take care of birthing people and their families so that they can show up as their best selves in this world.“

“With one of our postpartum clients, a call saying ‘I’m bringing food’ was a way to open a closed door without overstepping,” said Troy-Frazier. “[One] mom was not taking phone calls and resisting having postpartum visits. We were really worried about her mental health, and so our team agreed, let’s start with food. Let’s call her and tell her we’re bringing something hot for you to eat … ask her what kinds of fruits and vegetables she likes to eat … and that was the call that opened the door.”

Taking it one step further, “Fresh Future Farm prioritizes building relationships beyond the postpartum period, as many of pilot participants and their families continue to purchase food and farm-to-table meals from our grocery store, once they are financially able to do so,” said Tamazha North, co-director of food systems and projects at Fresh Future Farm.

North and Troy-Frazier, who are both optimistic about the future of the farm-to-postpartum-homes program, understand that there are specific obstacles that Black farmers, in particular, face. The ongoing fight for farmland, access to seed funding, and limited kitchen space to prepare meals and clean produce are challenges that directly impact how farmers are able to help families.

Nevertheless, partnerships with farmers, farm-to-table restaurants, and families like those in Charleston, Oakland, Atlanta — even community care systems like the family and friends who helped me in Nashville — are models that can positively affect necessary change not only in Black maternal health outcomes, but maternal health outcomes at large.

“We’re reconciling the truth that [farmers and birth workers] can take care of [birthing people and their families] so that they can show up as their best selves in this world. We tell our participants that they don’t have to pay us back. But seriously, not to be cliche, pay it forward. Help somebody else and tell them that they’re not alone,” said Troy-Frazier.