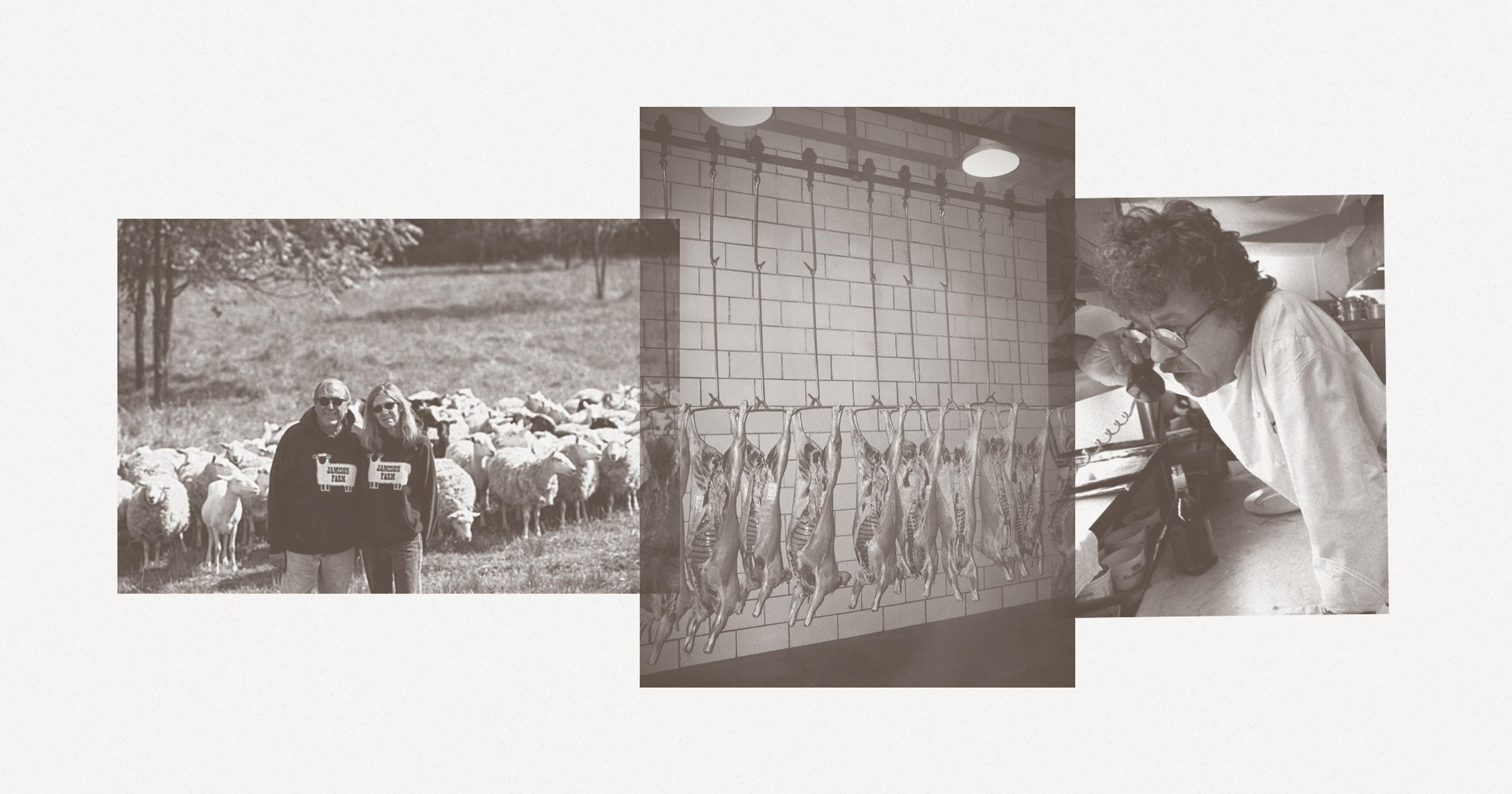

Sukey and John Jamison never intended to farm — never mind sell 5,000 lambs per year to some of New York’s finest restaurants.

Sukey and I did not come from a farming background. When we first bought our farm — by accident, really — we had roughly zero idea what to do with it. We had simply wanted to buy a beautiful old stone house, built in 1798, to restore over the years. The problem was that the seller would not sell us the house without the 65 acres of prime farmland that went with it.

Fortunately we found a neighbor who was happy to raise crops and keep purebred Ayrshire Heifers at our place. To keep the cows company, Sukey — a true “Earth Mother” in her heart — decided it would be fun to get a few sheep as a 4-H project for our kids. We bought one ram and a handful of ewes. We weren’t sure how it would go, but after some trial and error in the world of lambing, Sukey and the kids were learning to become very good shepherds.

Still, the idea to actually make money from our fuzzy new friends didn’t come right away. I was traveling around the country, selling coal, while Sukey had a local catering business. The sheep were still a hobby.

Things changed after one of Sukey’s customers, a high-powered Pittsburgh lawyer, wanted lamb for a dinner party. Sukey looked all over the area, but could not find any at local stores. On the verge of giving up, she realized the solution to that catering puzzle was right in our backyard. We brought some of our little brood to a local slaughterhouse; lamb was back on the menu! The lawyer loved our meat, and told all his friends. This was the beginning of something big, even if we couldn’t see it at the time.

Our launch into retail was still fairly modest. We started selling “freezer lamb” to some of our neighbors — whole lambs cut for storage. Over the next 10 years or so, we sold freezer lamb and purebred breeding stock on the side, but I didn’t quit my day job.

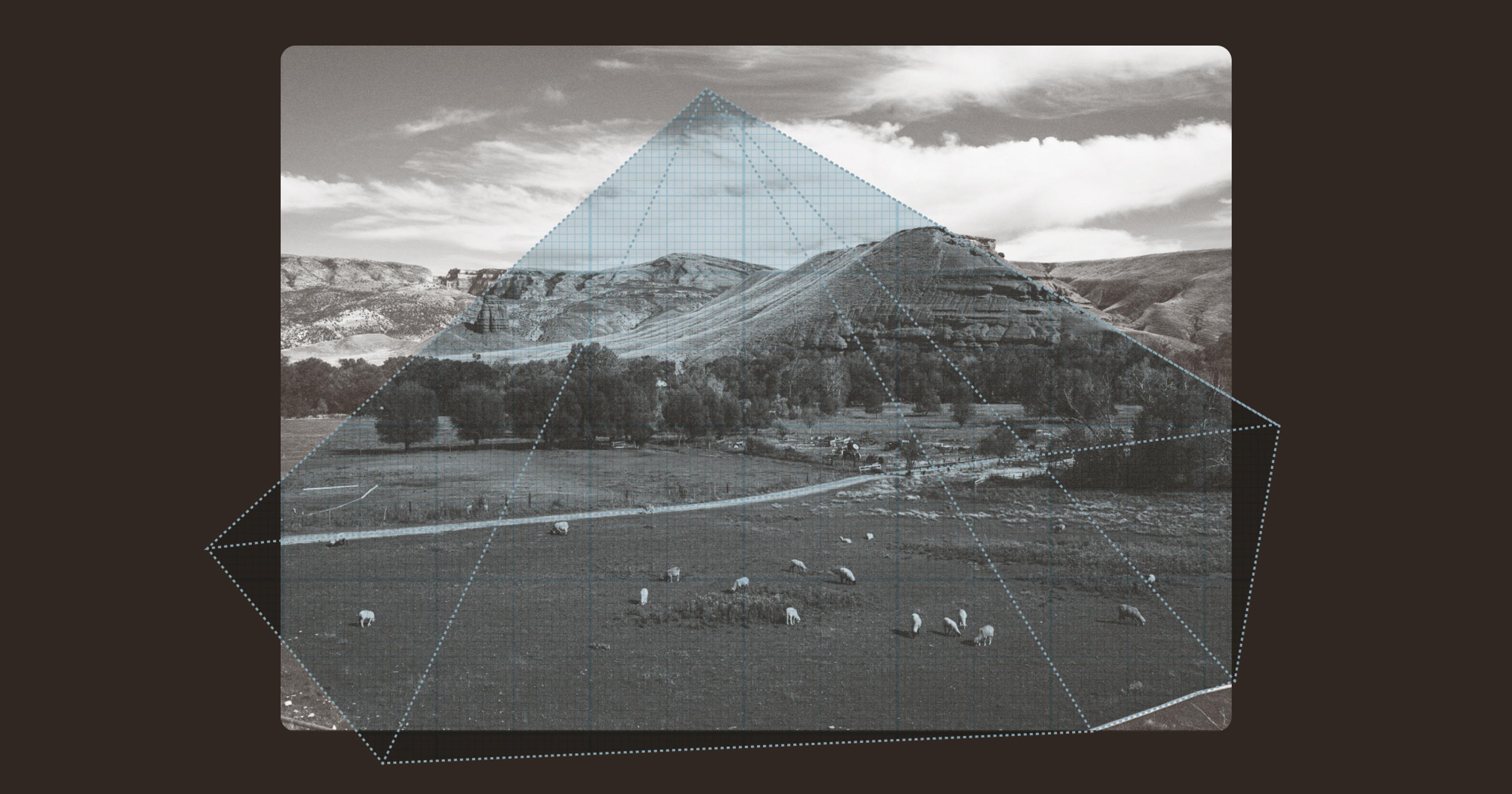

What kept me interested was the production advantage we had with our grass. Our area of Pennsylvania has some of the greatest grasslands in the country, which had supported large, highly profitable Merino flocks in the 1900s. As we say on this western ridge of the Appalachians, you can sit on the porch in May, drink a beer, and listen to the grass grow.

We were hoping that by fencing and utilizing these pastures, we could fatten our lambs without resorting to feeding them overpriced grain. Somehow utilizing these powerful grasses with hungry ruminants, our little 4-H project got out of hand.

We got into a discussion with Sukey’s father, a longtime television executive and a wary supporter of our dive into the sheep business. While he had initially supported purchasing an old stone house with 65 acres, he was not so keen on going into farming full-time. We were learning about sheep through trial and error, but we had not produced a true business plan.

Sukey — a true “Earth Mother” in her heart — decided it would be fun to get a few sheep as a 4-H project for our kids.

Her business-savvy father said that we needed to create a focus, centered on one product from the sheep. Wool was considered, but ultimately rejected — the profit margin seemed too thin. We went for the meat. We loved the meat! Lambs would be born in the spring, graze throughout the summer months, and be ready for market in the fall. Sounds easy enough, minus one tiny little issue: How would we sell it? Our rural corner of Pennsylvania was a wonderful place to raise animals, but a terrible place to sell them. There was simply not a big enough market.

Having wasted much of my youth reading comic books — or what the young folk now refer to as graphic novels — I was always a sucker for the ads on the back page. They always sold things like X-ray glasses, or 100 toy soldiers for a dollar. All these treasures could be sent directly to me; it was magic, the magic of mail order.

What if lamb could be sold in the same way as my childhood trifles? It seemed like a worthy experiment, to pay our mortgage and feed our ever-growing family. We started a mail-order business.

Like farming, we had no idea how we were going to ship frozen lamb through the mail. In 1985, the local UPS people, try as they might, could not figure out how to successfully and legally ship dry ice. We ended up taking our issue to the UPS Higher Ups; after some experiments in Styrofoam packing, we were in business.

Now that we had figured out how to ship it, we had to sell it. Knowing we had a superior product, naturally raised, coming from a small farm, my idea was that our market was full of customers on Park Avenue in New York. We’d reach them with little ads in the magazines they favored. As I imagined it, these fancy city shoppers were going to come home from work, pour a Martini, pick up their copy of Smithsonian or The New Yorker from the coffee table and peruse the ads.

Our rural corner of Pennsylvania was a wonderful place to raise animals, but a terrible place to sell them.

We established a small customer base from this technique, but our real break came from unpaid media exposure. A New York radio station and The New York Daily News both did features on us, with the novel angle of a couple of inexperienced yuppies breaking into the farm world. We’ll take it! This was free advertising, more effective than what you could pay for.

By the late ‘80s, we had developed a following of retail customers for a brisk Christmas and Easter mail-order business. Still, the rest of the year was tricky. We sold sheep fencing and catered events to fill the financial gap between mail-order seasons. After the Easter/Passover season, things were tough. We needed a new plan.

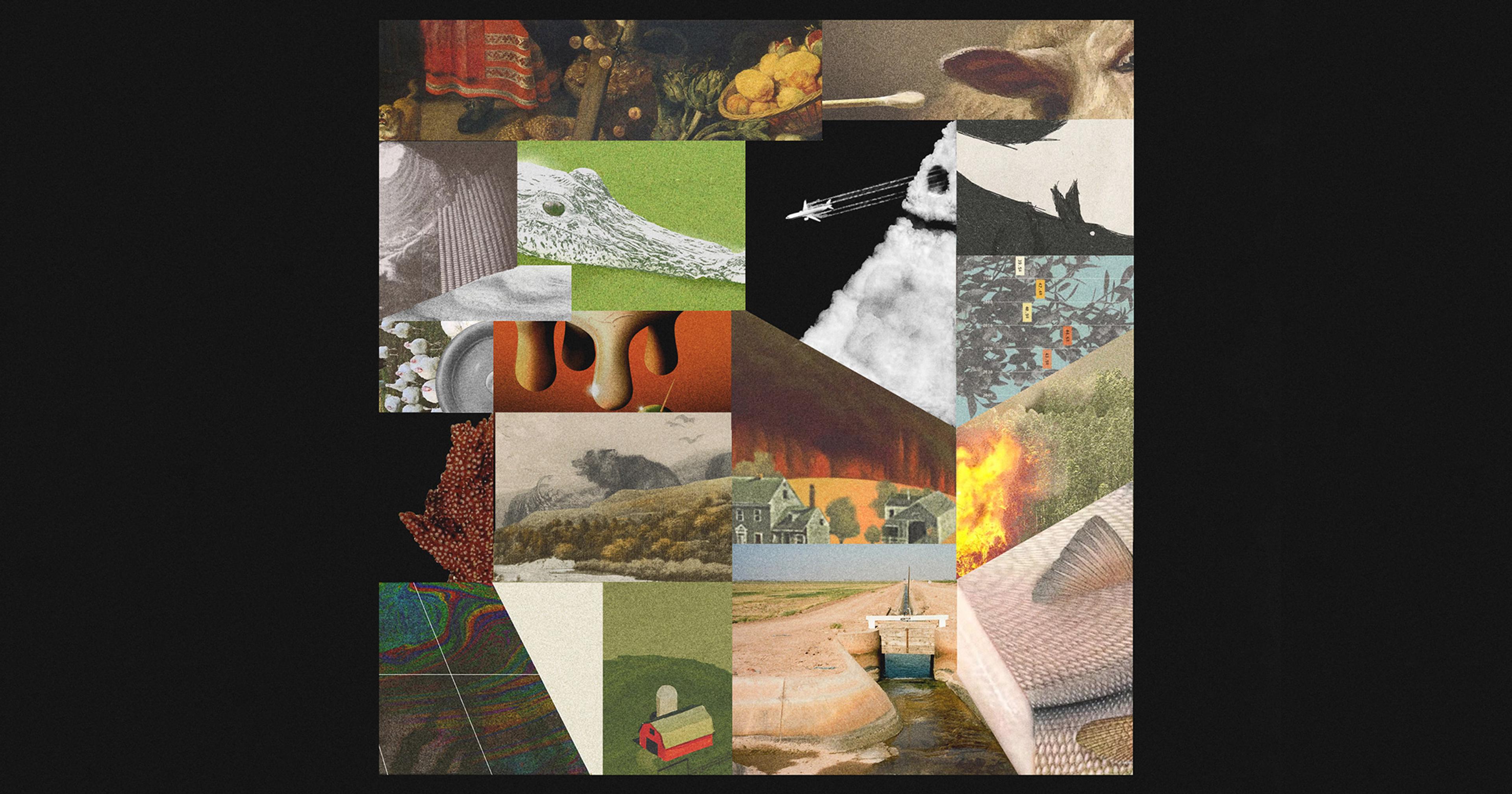

After an exhaustive review of our family connections, I was able to land a meeting with a big-time food authority in Pittsburgh, a chef by the name of Byron Bardy. Chef Bardy was the head of research and development at H.J. Heinz at that time, not to mention an experienced classical chef. If anyone could help, I figured it was him.

I launched into a rant about our lamb being a special product that nobody could appreciate because it was too expensive, too small, and too mild to be accepted by the mainstream; Chef Bardy listened politely. If I’m honest, I was meeting him because I saw no future in the lamb business; I wanted his negative opinion so I could find another career before I was too old.

I started to worry I would never be understood by a king of bottled ketchup, when Bardy said, “There will be a huge market for products like yours in restaurants.”

A New York radio station and The New York Daily News both did features on us, with the novel angle of a couple of inexperienced yuppies breaking into the farm world.

I disagreed. “You gotta be kidding me! I’ve been verbally and physically abused by every chef in Pittsburgh because it’s too small and too expensive. They told me, with raised voice: ‘This is Pittsburgh, kid. People want Flintstone-sized steaks. Plus, yinz price is outta line. Get owwt!‘”

But Bardy told me that restaurant food in this country was changing rapidly. There were chefs, he said, who were looking for special products from smaller producers. With Pittsburgh as my nearest culinary destination, a classic surf and turf (carp and kielbasa) town, it was very hard for me to see such a leap.

Chef Bardy went on, “Look, John. I am in charge of a fundraising dinner for the Children’s Hospital in October. The best chefs in the country will be there. It will be a perfect place to showcase your lamb.” I thought, here we go. We’re going down the tubes — let’s donate a bunch of lamb for a fundraiser, so we can go broke just in time to miss our mail-order season.

But Bardy kept going; he dropped exotic names such as Palladin, Prudhomme, and Puck, along with Ferdinand Metz, then-president of the Culinary Institute of America.

It was starting to sound intriguing, especially for Pittsburgh, but I still wasn’t convinced. At that point, the only restaurant I was selling to belonged to my childhood friend, who I suspected was trying to humor me.

We had gone from 14 ewes and 1 ram to selling almost 5,000 lambs a year.

I waited a week before I sent out PR letters to all the chefs on the list, stating we would be supplying lamb for the event. I asked them, “But in the meantime, would you like a sample order? Can I answer any questions?” Within two weeks, I had orders from Jean Banchet in Chicago and Larry Forgione in New York, not to mention Prudhomme and Puck! This restaurant business looked like it just might work. The phone started ringing; the business took off.

Within the next few years, we begged, borrowed, and stole in order to buy our own USDA slaughtering plant which enabled us to satisfy the demand created by weekly restaurant sales and seasonal retail sales. A few years after that, we were profitably producing value-added products which allowed us to utilize the whole carcass. Now we were truly vertically integrated, controlling quality throughout farming, processing, and sales. We also bought a bigger farm, nearly 212 acres. We had gone from 14 ewes and 1 ram to selling almost 5,000 lambs a year.

We were quite lucky, as I consider it. Sukey was a debutante from Cincinnati who now owned and operated her own slaughterhouse. I was a proper preppie who started business life as a banker, and was now slaughtering lambs myself. We had been destined for a corporate life with country club leisure, but things just didn’t work out that way.

Sukey was enamored with cooking, while I became fascinated with both grass production and animal processing. At first we listened to land grant professors tell us what and how we should feed the animals, then we followed our own path of grazing and listened to chefs suggestions for producing the best tasting lamb available. As our chef mentor Jean-Louis Palladin told me many times, “My only job in cooking your lamb is to not eff it up.” That’s quite a legacy to reflect on.