Why is this community farm nestled in Adirondack State Park giving away everything it grows?

It’s a sunny March afternoon and unseasonably warm in the High Peaks region of the Adirondacks. Farmer Adam Wilson is sipping tea at the wooden desk in his tiny house, and reading out loud from a book called Remembering Peasants: A Personal History of a Vanished World. A large window looks out across a soggy field and the bare vegetable garden to a grassy slope where a small herd of cows is sunning. It’s been three years since Wilson signed the deed to Sand River Community Farm – purchased in one lump sum of half a million dollars.

Farming isn’t the first thing that comes to mind when people think of the Adirondacks. Mountain wilderness, skiing and hiking, canoeing and camping, all draw millions of tourists to the area each year. But despite the harsh winters, up in the High Peaks region there’s a cluster of farms scattered across the mountain valleys and rocky alpine meadows. Right on the shore of Lake Champlain lies Essex Farm, one of the world’s only CSAs that feeds its members all year round, instead of only during certain seasons. Across Jay Mountain, tiny Sugar House Creamery milks twelve Jersey cows and makes award-winning cheese.

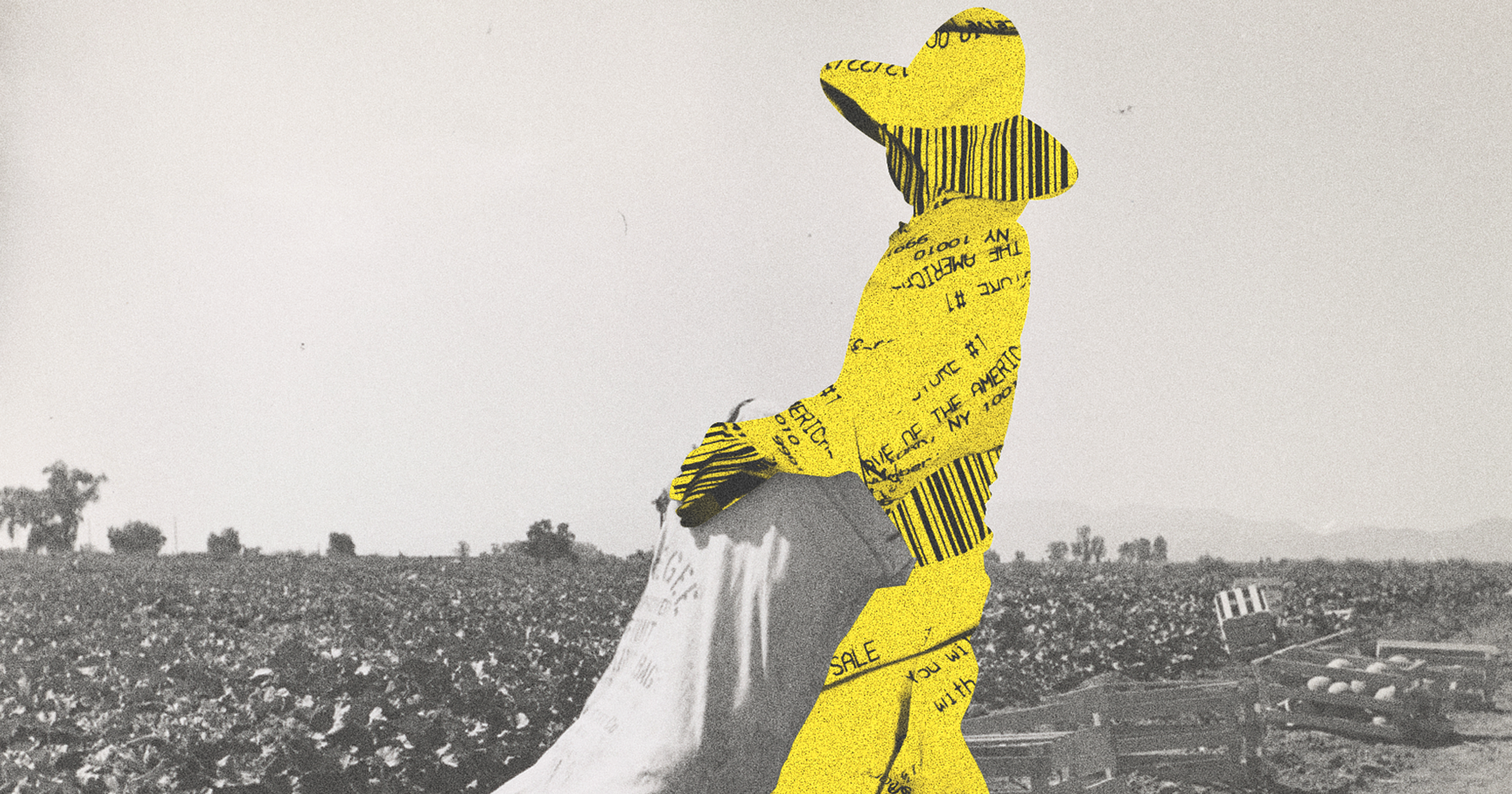

Yet local food remains beyond reach for many residents of Adirondack State Park. Those who spend time up in the North Country know there’s more to the Adirondacks than tourism: A hidden opioid epidemic accompanies an undercurrent of rural poverty in struggling towns and villages where logging and mining once paid the bills. Sand River is next to one of these towns – Keeseville – where lumber and iron processing in the 19th century made for a bustling hamlet, and local businesses produced everything from horseshoe nails to chairs.

Like many of America’s small industrial areas, circumstances changed over the course of the last century: lumber moved to the West coast, coal mines closed, factories went abroad. By the 1960s, the last big manufacturing operation in the area closed. In 2013, Keeseville residents voted – twice – to dissolve their village. One grocery store opened last December, but the owner admits that, since he’s been in Keeseville, three other stores have closed. For much of the last fifty years, this place – surrounded by some of the most fertile soils in the Adirondacks – has been a food desert. Some farmers have started taking food stamps or subsidizing CSA shares, but breaking down barriers to access remains a challenge.

The ‘Good Shake’

The farm Wilson runs is different from most others in the area. Nothing grown there is for sale at any of the regional markets. The farm isn’t on Google Maps; other than visiting its barebones website, the only way to find the location is a small wrought iron sign near the driveway that reads “Sand River Community Farm.”

Yet hundreds of people in the area have eaten food harvested from its soil. Just about anyone who stops by, whether on purpose or by stumbling upon it and getting curious, goes home with a frozen quart of soup. On the lid is a small sticker that reads: “This food is offered as a gift to anyone who is hungry for any reason.”

Sitting at the desk where he writes every morning, Wilson talks about his journey to Sand River Community Farm, which started around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Back then, he lived in Huntington, Vermont, and ran a bakery alongside a community farm. “I was footing all the bills with the bakery profit,” he says.

At the time, he’d read some books about the concept of a “gift economy” and was considering forming a nonprofit. The day before the pandemic was announced, he fell off his bed and broke his ribs. At that moment, lying on his back with no air in his lungs, he felt he’d reached a crossroads. He points at the corner of the desk, where a crack in the light wood reminds him of that day.

“I needed a good shake,” he smiles. “Now’s the time. Stop selling the bread. People are ready to consider things they wouldn’t have a week ago.” He decided he needed to commit to the idea he’d been ruminating on – that he needed to give everything away. So he opened a gift stand in Vermont in April, 2020: In those early days of the pandemic, neighbors in Huntington began exchanging gifts like sourdough bread and wine in a frenzy of exuberance.

Wilson’s stand was a rousing success, but there was no solid home base for the project. That is, until Ava, a member of the community, gave Wilson the most significant gift he’d ever received: half a million dollars from an inheritance to find the project a lasting place of its own. There was a farm for sale right across Lake Champlain. As Wilson explains, it was the last time that land would ever be sold.

“Now’s the time. People are ready to consider things they wouldn’t have a week ago.”

In his first months on what was to become Sand River, Wilson started to get to know his neighbors. Many were receptive to his ideas, especially some of the more seasoned farmers, who appreciated his emphasis on community and how he’d drop by with a package of ground beef from time to time. Younger folks showed up to volunteer on Sundays, and big crowds gathered for barn dances, singing, and community feasts all summer long.

The farm established itself as a local institution in less than two years, and Wilson incorporated the farm as a nonprofit. But he kept thinking about the neighbors who had never shown up – the ones hit hardest by life in a food desert. “How are we going to get the food to the people who need it most?” asks Wilson. “It’s been years trying to answer that question.”

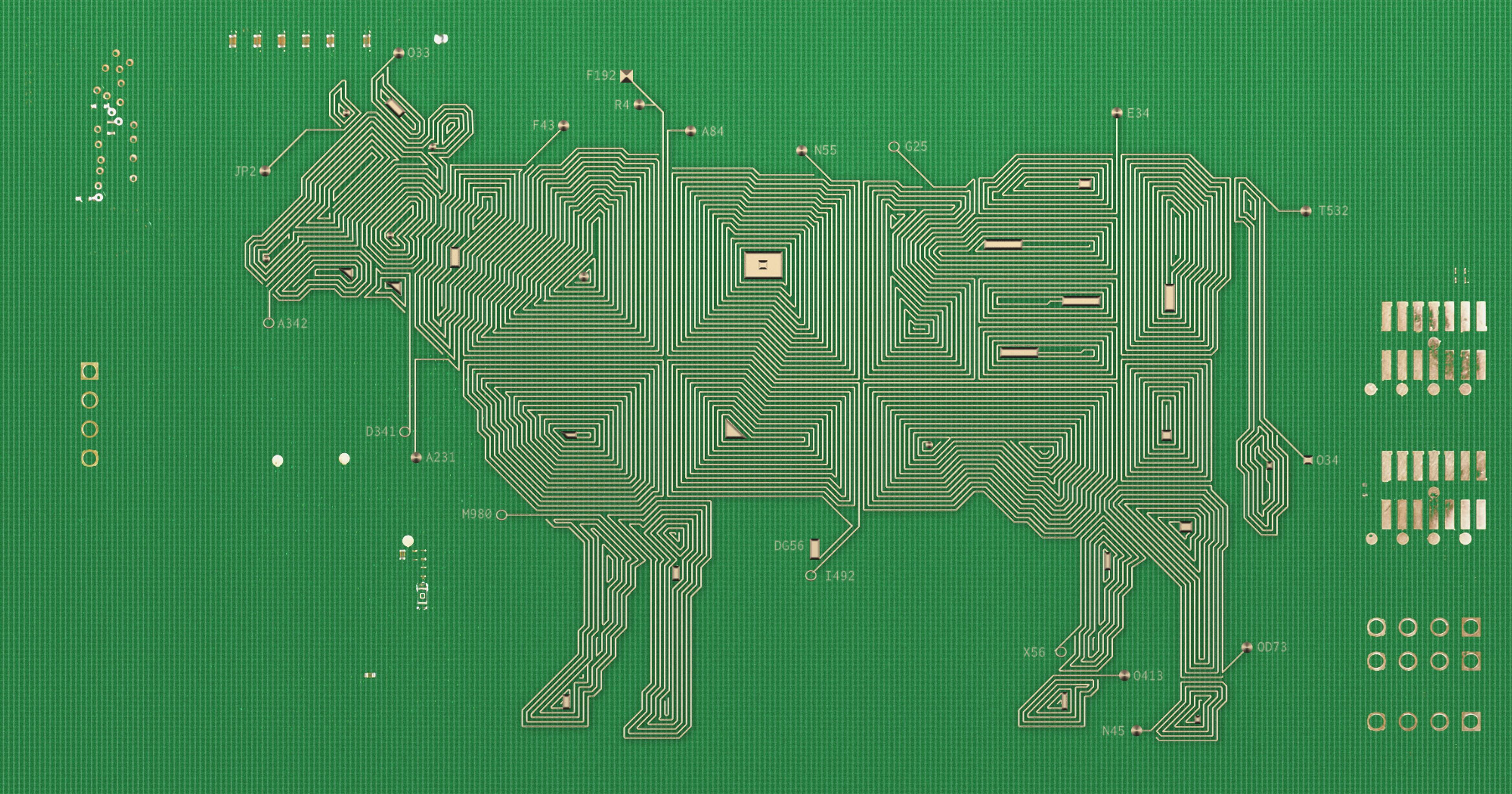

So far, the answer seems to come in the form of grass-fed lamb and beef and incredible vegetables that would be the pride of any farmer’s market. He doesn’t want to sell this food. But he believes his idea is much more than charity – it’s about building what he calls a “modern commons,” a place where nothing would be bought and sold, where the food would always be a gift, and where both the harvest and work could be shared by all the members of the community.

The Neighbors’ Gift

Saturdays, Wilson and a few others head down to Keeseville and open an informal “gift stand” on the place where one of the now-demolished grocery stores used to be. Anyone who stops by is offered a bowl of soup from a big five-gallon pot.

On a winter day last December, about a dozen people gathered around a brightly burning fire. One was an Ivy league graduate. Another, a dancing instructor. There was a social worker who stopped by with her daughter. Wilson started a conversation with her, asking for advice on how to reach some of the more vulnerable residents of the town.

“The gift offers me a way to meet my neighbors where I’m not selling anything,” says Wilson.

Not everyone is convinced. Last fall, Wilson and his friend Sam, who works with unhoused people in Burlington, gave a talk at a local Grange. At the end of the talk, an audience member challenged the privilege of being in a position to be able to give food away, without worrying about making ends meet.

Wilson acknowledges the discomfort. “The question about luxury is very important,” he says. He believes that food can be a way to bridge class divides. Every gift, no matter how small, is also an opportunity for an exchange, which means an opportunity to build community.

Not all of his neighbors think it will work. But the dozens who give up their Sunday afternoons to garden, make soup, and prepare the food to share, are practicing a neighborliness that they hope will revive their rural community – and one day, establish it as the modern commons Wilson has been dreaming of.