Recent enforcement actions have shined a light on tough workplace conditions and low wages for this $3 billion domestic industry.

While labor shortages in agriculture are a common refrain, the issue is particularly acute when it comes to growing mushrooms. Industry sources have said mushroom labor shortages are particularly bad, reaching up to 20 percent vacancy rates.

“Labor is still a challenge. I don’t think that’s changed much over the last 10 years,” said Lori Harrison, American Mushroom Institute’s director of communications.

Harrison added that finding “reliable” labor is the main difficulty, especially given the nature of mushrooms needing to be harvested around the clock with a short shelf life: “Reliable in the sense that people are here legally, and there are people who want to work. That’s what our industry advocates for.”

Meanwhile, labor advocates argue that it wouldn’t be hard to find workers if conditions were safe and compensation fair. On the heels of some high-profile regulatory actions this year, union organizers are trying to make inroads into the multi-billion dollar domestic industry, changing conditions they claim have become endemic.

“The working conditions in the mushroom barns are very hazardous. It’s dark. The air is rank. Many of the workers are forced to work non-stop 12-hour shifts with little or no time off to eat, rest or go to the bathroom,” UFCW’s Stan Raper said in a press release. “It’s like working in a 19th century coal mine.”

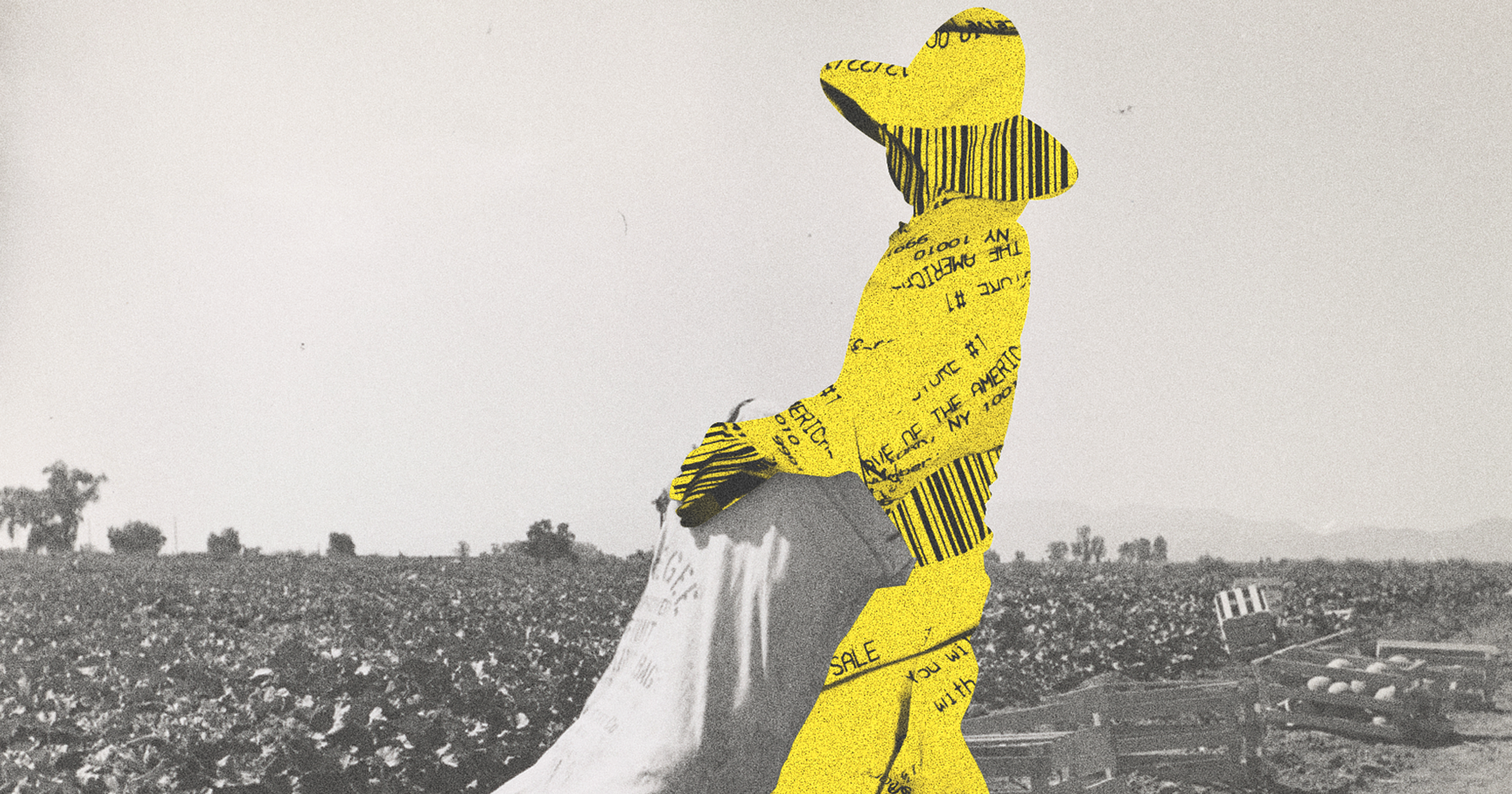

Rough Work

Mushroom harvesting often requires working long shifts in back-breaking positions, scaling high shelves, and 24-hour harvesting in dark rooms with poor air quality. Studies have shown workers are exposed to mold, bacteria, and mycotoxins, causing lung disease, allergies, and rashes, among other ailments.

This issue isn’t new. Way back in 1977, a report prepared by the Delaware and Pennsylvania Advisory Committees to the United States Commission on Civil Rights delved into horrible living and working conditions of mushroom workers including cramped conditions, exploitation, and “mushroom lung,” a type of occupational pneumonitis still observed in mushroom workers today.

“They are most of the time working in these very enclosed structures where there are very damp conditions … there are different molds and fungi that thrive in those conditions, and which are part of growing the mushrooms,” said Rebecca Young, director of programs at the advocacy group Farmworker Justice.

Young added that pesticides and residues tend to linger much longer than they would when applied in open air: “The conditions that are necessary in which to grow mushrooms aren’t always the healthiest conditions for workers to be in.”

“It was almost like this hidden industry that is slowly opening up and getting a bit more exposed.“

At two mushroom farms in Half Moon Bay, California, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) recently concluded workers were underpaid and living in unsafe housing conditions. Here, DOL found migrant workers living in “cramped cargo containers, garages and dilapidated trailers” at one site and in “moldy, makeshift rooms in a greenhouse infested with insects” at the other. DOL also recovered more than $450,000 in back wages and damages for 62 workers.

Also in the last year, Ostrom Mushroom Farm came under fire for mistreating workers in Sunnyside, Washington. In May 2023, the farm was found by the Washington Attorney General to be discriminating against female workers and Washington residents by intentionally replacing them with male guest workers from Mexico, and then retaliating against workers who made claims of discrimination or tried to engage with unions. The mushroom farm was ordered to pay $34 million to resolve a lawsuit asserting unfair, deceptive and discriminatory actions, alongside the egregious conditions.

“It’s over the last few years that we are starting to hear more … it was almost like this hidden industry that is slowly opening up and getting a bit more exposed to either the public eye or certainly the farmworker advocate,” Young said.

Who Can Fix This?

Raising wages and addressing these conditions — something union reps have been agitating for of late — would seem to be the simplest means to attract new workers. That said, the owners of mushroom operations have placed blame elsewhere, including post-pandemic industry recovery, lack of automation, and younger workers preferring office jobs. A common lament is that some percentage of each year’s mushroom harvest is being lost without enough workers to pick and process it.

“For a company our size, that’s maybe 10-20% of production not being harvested right now,” Shah Kazemi, owner of now-shuttered Monterey Mushrooms in Watsonville, California, told industry publication The Packer in late 2021. “Large or small, we’re all suffering from the same shortage. And mushroom consumption is on the rise.”

Industry insiders have also argued that the specialized nature of mushroom work limits the hiring market — mushroom harvesting is an extremely manual process that requires handpicking and delicate handling. As Sean Steller of Phillips Mushroom Farms, a leader in U.S. mushroom production, said, “There are countless factors impacting the labor market, but a few specific to mushrooms include intense competition and specialized skill requirements.”

“Large or small, we’re all suffering from the same shortage. And mushroom consumption is on the rise.”

Union reps point out how little of the mushroom industry is unionized, and is often built on low-cost foreign labor — the Watsonville companies were employing workers under H-2A visas, provided to temporary agricultural workers from outside the U.S. “In the union mushrooms, there is no labor shortage. Our workers are well-paid and stick at that job for decades, if you treat them fairly and you pay them well,” said UFW’s Antonio De Loera-Brust.

“This narrative of there being a labor shortage … that’s just completely untrue,” he added.

De Loera-Brust and his colleagues have faced steep pushback in their unionizing efforts, leading to the filing of multiple retaliation complaints. Additionally, existing U.S. law makes it extremely difficult for farmworkers to unionize. Harrison of the Philadelphia-based American Mushroom Institute said she has not heard of any unionizing efforts taking hold in her state, where more than 60% of the country’s mushrooms are grown.

Some progress is still being made, however. Migrant farmworkers in British Columbia made history this year when 390 new members unionized, representing the “largest group of farm workers in Canadian history to join a union” at Highline Mushrooms. And despite the challenges against farmworker collective bargaining outside New York and California, workers’ movements are taking hold in Washington as well.

The Path Ahead

Companies like Mycionics and 4AG Robotics say their robot mushroom-pickers can revolutionize the mushroom picking industry. In some cases, the machines can pick constantly for 24 hours, harvesting each mushroom at its ideal time instead of being restricted to human working hours and shifts.

Proponents also say automated harvesting and data analytics increase food safety and disease detection, but workers’ rights advocates are skeptical of how far this technology would go toward helping workers within the current system.

“If technology can make workers’ jobs less physically demanding [and] safer then we’re all for it. But if it’s going to just be used as a labor cost saving measure to eliminate jobs, and increase productivity without increasing wages, then obviously we’re going to be extremely against it,” De Loera-Brust said. “Technology is morally neutral; it’s the power dynamics of the workplace in which it is being introduced.”

Supporters of robotic mushroom picking claim it is highly scalable, too. Since mushroom farms around the world have common infrastructure, companies can develop systems for multiple farms without having to customize them to each operation.

“Technology is morally neutral; it’s the power dynamics of the workplace in which it is being introduced.”

But the technology is emergent; advocates say haven’t seen these solutions trickle into the workplace yet.

“We’ll believe it when we see it,” said De Loera-Brust. “At some point, presumably the technology will get there. I don’t know if it’s going to be the next 10 years or in the next 100 years, but when it does get there, we want workers to be in a position of strength, to be able to negotiate terms for how that technology is used.”

The American Mushroom Institute did not respond to detailed questions about the conditions in mushroom barns and overall treatment of migrant workers.