More than 90 percent of land-based wind turbines operate on private farmland. But when a wind company comes calling, the response from farmers and their neighbors can be hard to predict.

There is a mound of concrete shaped like a Hershey Kiss buried in the middle of Clayton Rosenberger’s corn and soybean fields in McClean County, Illinois.

Bolted to the tip of the Kiss, around ground level, is a wind turbine. After watching the construction of the turbine from his porch over eight months, Rosenberger was amazed by the efficiency of the process. The bottom of the concrete Kiss rested 12 feet below the ground’s surface. The dirt removed to make the hole for the Kiss is poured and packed up to its pointed top, at the junction with the turbine, so it appears sprouted from the ground when Rosenberger looks out over his fields.

The single turbine takes up about two-thirds of a football field of land, including the ground-covered concrete and surrounding gravel, or 0.1 percent of Rosenberger’s 1100-acre farm. With a blade position at 12 o’clock, the turbine stands at 499 feet tall, one foot shy of the county’s height limit.

The turbine began spinning four years ago, and with each rotation, Rosenberger makes money. “I’m a self-employed farmer. I don’t have a 401-K,“ Rosenberger said. ”I don’t have a retirement plan, but now I do.”

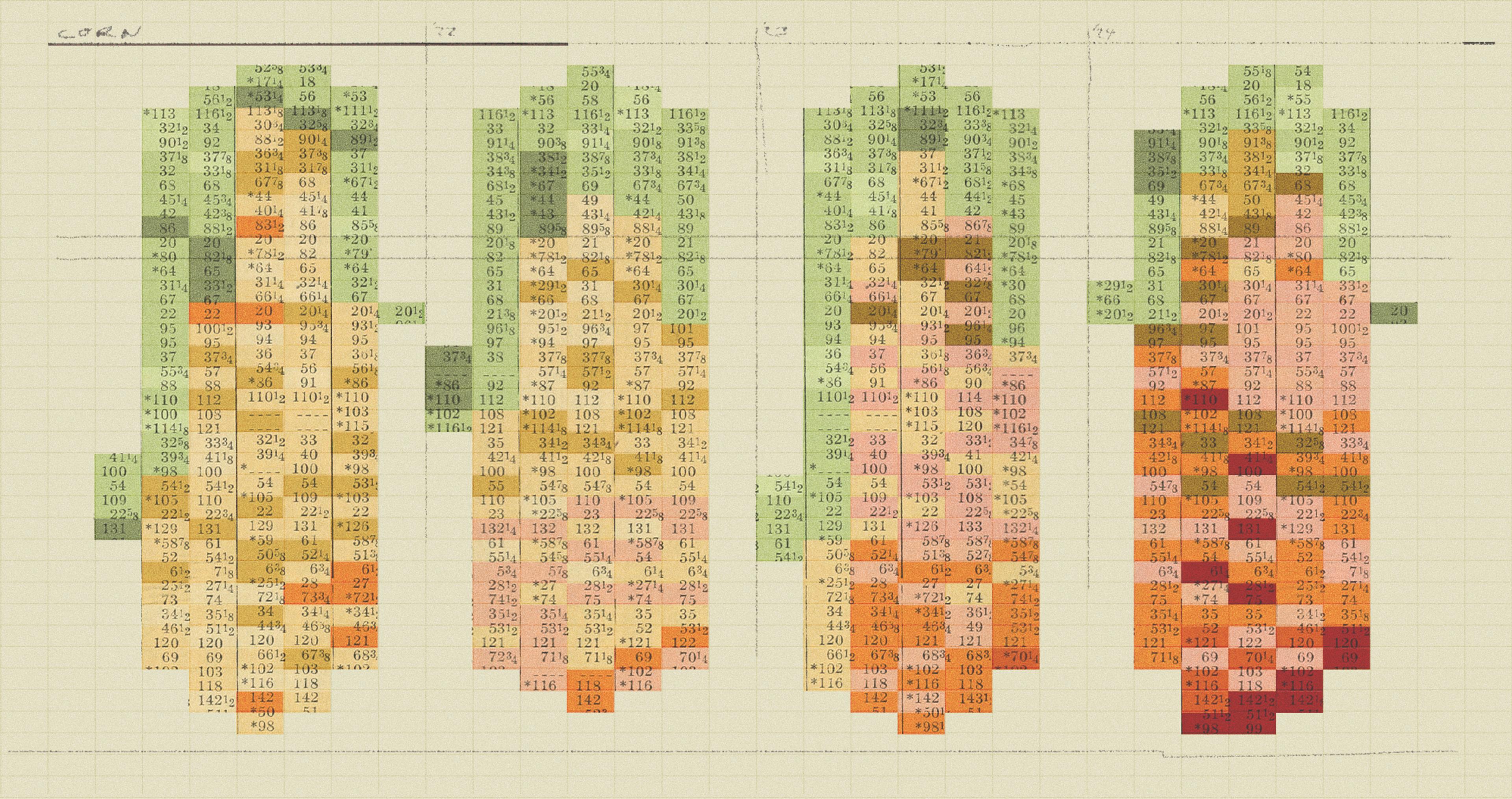

More than 90 percent of the land-based wind turbines tower over private agricultural land. In 2000, there were around 14,300 turbines operating across U.S., Guam, and Puerto Rico. In 2010, the number more than doubled to 36,000 turbines. By the end of 2024, 74,695 turbines dotted the country.

The energy generated by wind has grown at an even faster rate, now that turbines are taller with larger blades, with higher capacity for energy conversion. Between 2000 and 2023, annual capacity for wind energy jumped 65 times, from 0.1 gigawatts to 6.5 gigawatts. Over the last 25 years, the industry has generated a cumulative 150 gigawatts of energy across the U.S.

Money is clearly the main reason that farmers have leased land to wind companies in the last three decades, said Julia McPherson, community relations manager for wind company EDP Renewables, who owns the turbine on Rosenberger’s land. Contracts with wind companies provide a regular income “to help hedge against the ups and downs of agriculture,” McPherson said. “It really helps keep family farms in families.”

On average, farmers who add turbines to their land make between $8,000 and $33,000 per year, according to a report by the USDA that looked at wind energy costs between 2011 and 2020. In another study, the same USDA researchers found that between 2012 and 2017, 94 percent of farmland remained agricultural in its primary use after a turbine was placed on the property.

John Dollinger of Grundy County, Illinois, has 10 turbines spread across his family’s 800 acres of farmland. A wind company started paying him an annual $10,000 per turbine around a decade ago when the contracts were signed. The annual pay goes up with the consumer price index each year — now, each turbine brings in around $12,000 per year.

“I’m a self-employed farmer. I don’t have a 401-K. I don’t have a retirement plan, but now I do.”

But despite the money, and despite the ability to continue farming, not all farmers and their neighbors are on board with wind energy. Wind is a hyperlocal issue, popular in some communities, opposed in neighboring ones; championed by some farmers, but garnering indifference or distrust from others. While some like Rosenberger and Dollinger view it as a financial safety net, increasing the value of each acre of their farm, others see wind turbines as an imposition, a detraction from the hard work they’ve given to their land.

In Pershing County, Nevada, alfalfa farmer Randy Scilacci would be quick to turn down a wind company, should they approach him. “No, I’ve worked too hard to get to where I am at to let somebody do something like that.”

Over his three decades of farming, he’s watched wind and solar get “pretty big here, out West.” His area of Nevada is more prone to solar projects, but he turned down the only solar company that contacted him.

His main concern — what “scares me more than anything,” he said — is the trend of losing precious farmland. New construction in rural areas is partly to blame. But wind and solar, Scalacci said, are part of this problem.

Every access road, every cement base around a turbine, removes cropland, he said.

“You’ve only got so much farm ground, and there’s 1% of the population that feeds the rest of the country, and you go taking that stuff out, then you’re putting more pressure on the farmers that are farming to do more,” Scalacci said.

In addition, wind companies rely on federal subsidies, Scalacci said, and without the subsidies, he can’t imagine how the business of wind would be profitable.

What “scares me more than anything” is the trend of losing precious farmland.

The Inflation Reduction Act included tax incentives for wind projects, which ended in 2024. President-elect Trump has opposed wind energy, and has said recently that he would not subsidize new wind farms and does not “want even one built” during his time in office. His pick for the Department of Energy, Chris Wright, CEO of oil and gas company Liberty Energy, has denied the existence of climate change and stated that we are not in an energy transition in a video posted to his Linkedin page.

Farmers and rural landowners who don’t like wind turbines are often concerned about noise and shadows, McPherson said. Others find that turbines interrupt the idyllic view. The increasing height of turbines also gets brought up, she added. In the Midwest, farmers worry about construction damaging their drain tiles or compacting soil.

There has always been opposition to wind, sometimes in an organized fashion, other times just a general negative sentiment or reticence, said McPherson of EDPR. Those concerns are not new.

But “with the way that political tides have shifted, it’s become much more of a partisan issue” in the last decade or so, McPherson said, even though the company experienced record growth under President Trump’s first term in office.

Over a dozen House Republicans asked Speaker Mike Johnson to not gut the Inflation Reduction Act in a letter sent in August 2024, pointing out how much economic investment by clean energy manufacturers helped their rural districts.

“With the way that political tides have shifted, [wind energy has] become much more of a partisan issue.”

McPherson said wind energy injects millions of tax dollars into a local government with a “lighter touch” with “way lower intensity” than, say, an Amazon distribution center or a factory, which take up more land and changes the community.

One state to the east of Rosenberger’s turbine, in Rush County, Indiana, Michael Dora’s farm sports no wind turbines. This, despite Dora signing a lease with a wind company nearly seven years ago.

Dora, now Indiana director of the non-profit renewable energy advocacy group Farm-to-Power, still gets worked up when explaining why the lease never led to a turbine standing tall above his grain fields and herds of livestock.

The opposition to wind energy was fierce in his county. Neighbors who lived tens of miles away from his farm expressed concern at public hearings about wind companies moving into their county. They brought up how the turbines would change the landscape or could mess up drainage on neighboring farms. Leaders waffled under the pressure, Dora said. The wind company eventually abandoned the project, voiding existing contracts with Dora and countless other landowners. Afterwards, the county imposed a moratorium on future wind projects.

Wind turbines tend to generate fear and misinformation in communities, said Insurance Commissioner Glen Mulready of Oklahoma.

“There may be reasons you want to oppose a wind farm here in your county or in your area, but insurance isn’t one of them.”

A misconception that Mulready often hears from Oklahoma farmers and rural neighbors is that a turbine would prevent them from obtaining homeowner insurance. This is untrue, Mulready said at a meeting in Lincoln County, Oklahoma in June, and later repeated to this reporter.

In fact, in 2011, Mulready pointed out that Oklahoma passed a law requiring wind companies to add the landowners to the company’s insurance policy. This provides another layer of protection to the farmer, he said. “So they get more coverage than your regular homeowner,” Mulready added.

After a turbine failure or fire, which happens to between 1 in 2,000 and 1 in 7,000 turbines but is thought to be underreported, insurers might pass off the cleanup costs to the wind company as a liability claim, Mulready said. But the farmer wouldn’t see any of that behind-the-scenes accounting.

“Look, there may be reasons you want to oppose a wind farm here in your county or in your area, but insurance isn’t one of them.” he said.

Disruptions to farming operations is a top concern for farmers about wind turbines, said Sarah Mills, associate professor of practice in urban and regional planning at the University of Michigan. Mills conducted a survey of farmers in Michigan regarding wind energy between 2013 and 2014, back when the average wind turbine stood around 400 feet tall. (Now, turbines average 550 feet from the base to the tip of the top blade.)

Soil could get compacted, and drain tiles might get broken, when the large cranes walk turbine pieces across the land, the farmers said. Fires or lightning strikes to the turbines might damage a batch of crops, such as the fire at the Eight Point Wind farm that littered fiberglass across hayfields in West Union, New York. Older turbines might need to be removed after decommissioning. That said, all of these should — and often are — covered in a wind contract, so farmers are compensated for farming disruptions and lost crops.

“I think part of it is they were just a little jealous that they don’t have one.”

Neighborliness is another concern, Mills found. Some farmers worried about becoming unpopular with neighbors if they sign on to a wind farm. Wind energy is more contentious in areas where aesthetics are valued higher than land productivity, such as in Michigan, where one is always within six miles of a body of water, Mills found.

Payment models can help smooth — or exacerbate — tensions.

Farmers are paid in two ways, Mills explained: a fixed rate for having the turbine on their property, or a percentage of the money made by selling the electricity to the grid. Some leases are a combination of the two payment types.

But other payments may be made to landowners near the turbines, a “participatory payment” as a thank you for the eyesore that turbines are sometimes considered to be. Other neighbors might also receive a one-time construction payment during the months of digging, pouring of cement, and trucking of equipment to and from the turbine site.

Another factor is the decreasing number of newer, larger turbines needed for each wind farm. Fewer people get big payments, Mills noted, but more people are affected by the taller towers. Even with neighborhood payments included in the leases, Mills does not think that leases are adapting to the trend of larger but fewer turbines.

“I think this kind of [lease] model not evolving, is creating more haves versus have nots,” Mills said.

So, it’s often the case that farmers who stand to gain financially from a wind project tend to be quiet about their decision, Mills noted in her research study.

Jealousy may play a role. In central Illinois, Rosenberger heard notes of disappointment masquerading as opposition from neighbors whose farms were not considered for the wind farm. Some had land too close to the town, while others just were not located in the windy plains of the region. “I think part of it is they were just a little jealous that they don’t have one,” Rosenberger said.

“It’s a good thing all the way around. I know some people probably don’t like it, but they’ve gotten used to it.“

Wind turbines also do not uniformly benefit farms, Mills found in her research. Typically, larger agricultural farms benefit more than smaller enterprises — a common outcome in the farming world.

Companies need around 80 to 100 acres around each turbine to catch enough wind to be profitable. But it’s best to align wind turbines across many hundreds of acres in order to catch the best wind dynamics, so having access to more land is better for the companies.

In one rare example, small farms in northern Michigan banded together to craft a revenue-sharing wind contract that suited their community. Every acre involved in the community wind farm — regardless if the landowner hosted a turbine — got paid the same per acre rate, according to reporting by Reimagine Rural. The farmers would also get a share of the profits should the wind farm turn out to be more profitable than anticipated. They shopped the contract out to wind companies. The Isabella Wind Farm started operating in 2021.

Rosenberger’s farm on the prairies of central Illinois had the three ingredients necessary for a wind turbine: access to wind, a nearby connection to the grid, and no environmental restrictions. That is why EDPR approached him.

At first, Rosenberger and his wife did not want a wind turbine on their land. They did not like the look of them. And what would it sound like, they wondered? They took a trip down to a wind farm 25 miles or so south and parked their car beneath a turbine close to the road. The faint whooshing with each rotation was much quieter than they thought it would be. “Well that ain’t that annoying,” Rosenberger said he thought at the time.

Then Rosenberger learned that the neighboring farms on which he worked and plowed, but did not own, would be getting turbines. If his daily life was going to include the four turbines for him to plow around on these other farms, why not a fifth on his own land?

The finances sealed the deal for Rosenberger. He would lose roughly an acre and a tenth from his 1100 acres of farmland, but the turbine would make up that money and more. He was the last landowner to sign the lease for his area’s wind farm.

Four years later, Rosenberger doesn’t even notice the turbine any more. If he’s sitting on the patio in the evening, he can hear a faint whoosh sound of it spinning, which increases to a small aircraft taking off on the windiest of days. The blades throw shadows over the yard during certain times of the year, but he lives too close to the tower to notice the red light flashing.

He can square up his plowing around the turbine base. And he doesn’t worry about lightning strikes, even though three nearby turbines have been struck over the years. EDPR, which leases Rosenberger’s land, would compensate him for the damage.

The township of just six square miles and 300 residents is benefiting from the taxes as well, Rosenberger said. When he was a township official, prior to the wind farm coming into the area, they could barely make ends meet. Now, new fire trucks drive on repaved roads.

“It’s a good thing all the way around. I know some people probably don’t like it, but they’ve gotten used to it. I think because you just don’t hear any rumblings in the neighborhood about them.”