Yaupon holly, a once-forgotten caffeinated plant native to this continent, is one of this year’s hottest food trends.

The big-city dwellers drink it black, in ceramic mugs with intricate decorative patterns. Sure, it’s a luxury that has to be imported from faraway growers, but no big meeting gets started without the caffeinated buzz it provides.

Is this New York City’s coffee habit? Perhaps. Yet the same language would have worked nearly a millennium ago to talk about the residents of Cahokia — then the largest known Indigenous settlement in the present-day United States — and their appetite for yaupon holly.

Chemical traces on excavated pottery suggest that Cahokians shipped yaupon, one of only two caffeinated plants native to North America, hundreds of miles from the Gulf and South Atlantic coasts to what’s now the St. Louis metro area. There the leaves were brewed into a “black drink” downed before important religious or political events. Early European colonists also took to the beverage, even sending it back to the homeland as “Carolina tea,” and American revolutionaries drank yaupon in protest of British tea taxes.

Yet as competition from imported tea and coffee intensified, white settlers started to associate drinking yaupon with negative racial stereotypes. In 1789, a British scientist gave the plant the unflattering scientific name Ilex vomitoria based on reports of Indigenous rituals involving the drink. Abianne Falla, co-founder and CEO of CatSpring Yaupon in Texas and a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation, said “yauponer” eventually became a derogatory term of poverty and backwardness.

“In the South, most of the people who drank it were Indigenous — who were then forced to relocate and largely eradicated — or slaves, because they couldn’t afford imported caffeine,” Falla explained. “Historically, it’s just been a drink of the marginalized.”

But Falla and a growing number of other producers now believe the plant can reclaim a place in America’s broader caffeine culture, especially as climate change threatens its more popular replacements. Bryon White, co-founder and CEO of Yaupon Brothers American Tea Co., is one of yaupon’s biggest boosters.

Although he grew up surrounded by the shrubby evergreen’s dark leaves and bright red berries in coastal Florida, White didn’t know its beverage potential until he came across Black Drink, an ethnobotanical history of yaupon compiled in 1979. “This must taste like shit, or else somebody else would be doing something with it,” he recalled thinking.

To White’s surprise, his experiments with brewing yaupon leaves like black tea yielded an agreeably earthy flavor, similar to that of South American yerba mate (a close botanical relative). And with caffeine levels per weight about a third less than coffee, the resulting buzz was pleasantly mild.

“This must taste like shit, or else somebody else would be doing something with it.”

“There really was and is no salient reason why yaupon is not popular, not part of the mainstream culture. The main contributing factor is that it’s a consequence of the erasure of Indigenous people,” he said. “Upon learning that, it felt like maybe an obligation to bring this thing back.”

(White is not Indigenous, and he is aware of the plant’s complicated narrative. “Yaupon has been used as an important food, medicine, and ceremonial item by Indigenous people for thousands of years. We want to tell that story in a way that pays respect to native people, and we believe firmly in the native food rematriation movement,” reads the company’s website, noting that 5% of online sales are donated to an Indigenous food systems nonprofit.)

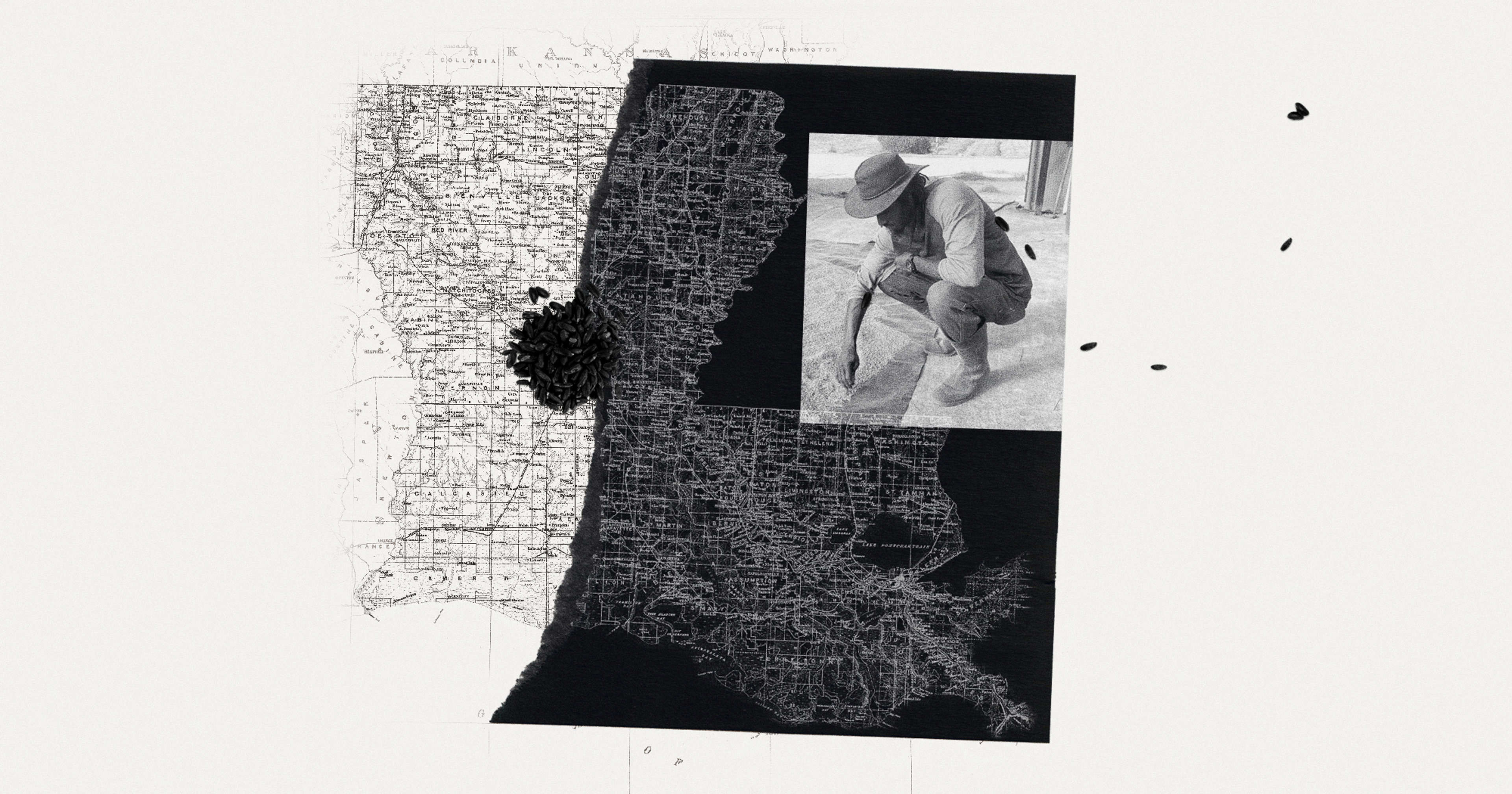

Bryon and his brother Kyle became some of the country’s first modern yaupon entrepreneurs upon starting their company in 2012. Until 2023, the business relied entirely on wild yaupon; the plant is relatively common across its range, and it springs back quickly after pruning. Even today, Yaupon Brothers maintains access to roughly 80,000 acres across Florida with naturally occurring yaupon, and Bryon White said wild harvesting still represents about 90% of the company’s supply chain.

Most other yaupon businesses continue to use entirely uncultivated material. Falla said she sources 50-60 tons of wild yaupon leaves per year for CatSpring, from about 1,100 leased acres of certified regenerative organic ranchland, enough to provide wholesale amounts for national brands like Sweetgreen and True Food Kitchen. “To be totally candid, our long-term sustainability plan is to be clearing yaupon and reintroducing native grasses as we go,” Falla said, noting that many cattle farmers see the plant as a nuisance on their pastures (it’s not great for grazing).

But the labor-intensive harvest process and seasonal variations of wild yaupon led the Whites to explore farming the species. Because yaupon seeds can take 18 months or more to germinate, they partnered with a tissue culture laboratory called Agri-Starts in 2017 to mass-produce clones of two yaupon plants selected from the wild for their particularly robust production and large leaves. The firm can now generate about 40,000 starts every month, enough to plant roughly 13-20 acres.

“Historically, it’s just been a drink of the marginalized.”

Since 2021, Bryon White said, about a dozen farmers across Florida, Mississippi, and Alabama have together put nearly 250,000 yaupon trees in the ground, with the first harvests taking place last year. Each acre of cultivated plants yields about 1,700 pounds per harvest, up from about 700 pounds for a good wild plot, and he anticipates reaching 2,500 pounds per acre from mature cultivated trees.

Yaupon Brothers plans to establish its own farm with 25,000 plants at its new headquarters, a defunct citrus grove in Crescent City, Florida. The company’s long-term goal is to capture 1 percent of the American tea market, worth about $130 million, which will require about 20 to 40 million trees under cultivation.

While White, who is also vice chair of the American Yaupon Association, said yaupon holly has no major disease problems and is remarkably resilient to environmental stressors like drought, he admits there’s much the industry doesn’t know about the crop. The yaupon genome hasn’t been sequenced, and there’s little formal guidance around agronomic practices like fertilization or pest management.

Yaupon Brothers is partnering with the University of Florida to help answer some of those questions. Wendy Mussoline, an extension agent with the university’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, said that work is still in preliminary stages but that she and her colleagues are particularly interested in how fertilization impacts yaupon’s caffeine levels.

Scientists do know that yaupon’s global competitors are in trouble. A paper published by a team of Brazilian researchers earlier this year, for example, found that up to 75% of that country’s coffee-growing regions could become unsuitable for the crop by 2100 if current warming trends continue. Tea production in major exporter nations like Kenya and China is also coming under stress as humanity’s carbon emissions make temperatures hotter and rainfall less predictable.

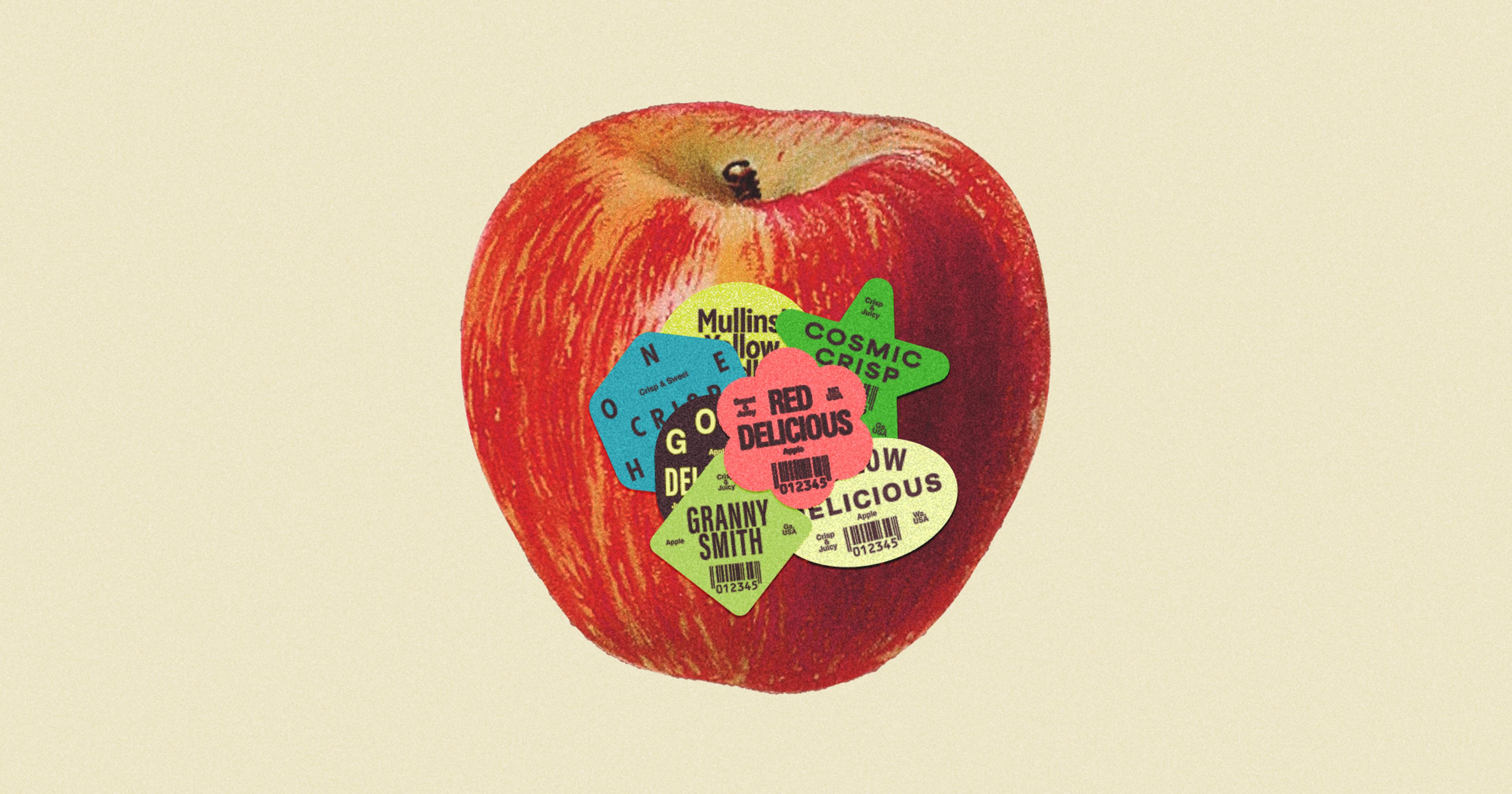

Whole Foods named the plant its top food trend of 2023.

And the very act of importing tea or coffee thousands of miles using fossil fuels, instead of relying on America’s own caffeine source, looks ever less defensible in the face of climate change, argued White. “When it gets here, we’re dunking it in hot water for five minutes before dumping it in the trash,” he said. “It’s kind of an extreme example of wasteful consumerism.”

Yaupon appeals to many beverage makers as a domestic option; Whole Foods named the plant its top food trend of 2023. While coffee remains the country’s dominant caffeine source, drunk on a weekly basis by 75% of American adults, many customers show an increasing willingness to explore alternatives like yerba mate and matcha tea.

Infruition Tea in Asheville, North Carolina, also launched a yaupon product last year. Infruition founder Brad Smith said yaupon’s American-grown origins meshed well with his company’s organic, locally sourced focus.

Yaupon is one of Infruition’s most expensive ingredients — Smith buys yaupon from Savannah, Georgia’s, Yaupon Teahouse at about $15 per pound wholesale, compared to about $5 per pound for black tea — but he thinks gaining a toehold in the rapidly expanding market is worth the investment. “I don’t think it would have seemed like a viable option if it wasn’t growing in popularity,” he said.

Infruition’s canned sparkling yaupon blends the plant with strawberry, mint, and keemun black tea. Cahokians might not recognize the effervescent, lightly sweet beverage as a relative of their cherished black drink, but Smith said it has been very popular.

“I have found that most people have not heard of yaupon, but they are very receptive to it due to its sustainability,” Smith said. “If I had to answer how customer response has been in one word, I’d say ‘outstanding.’”