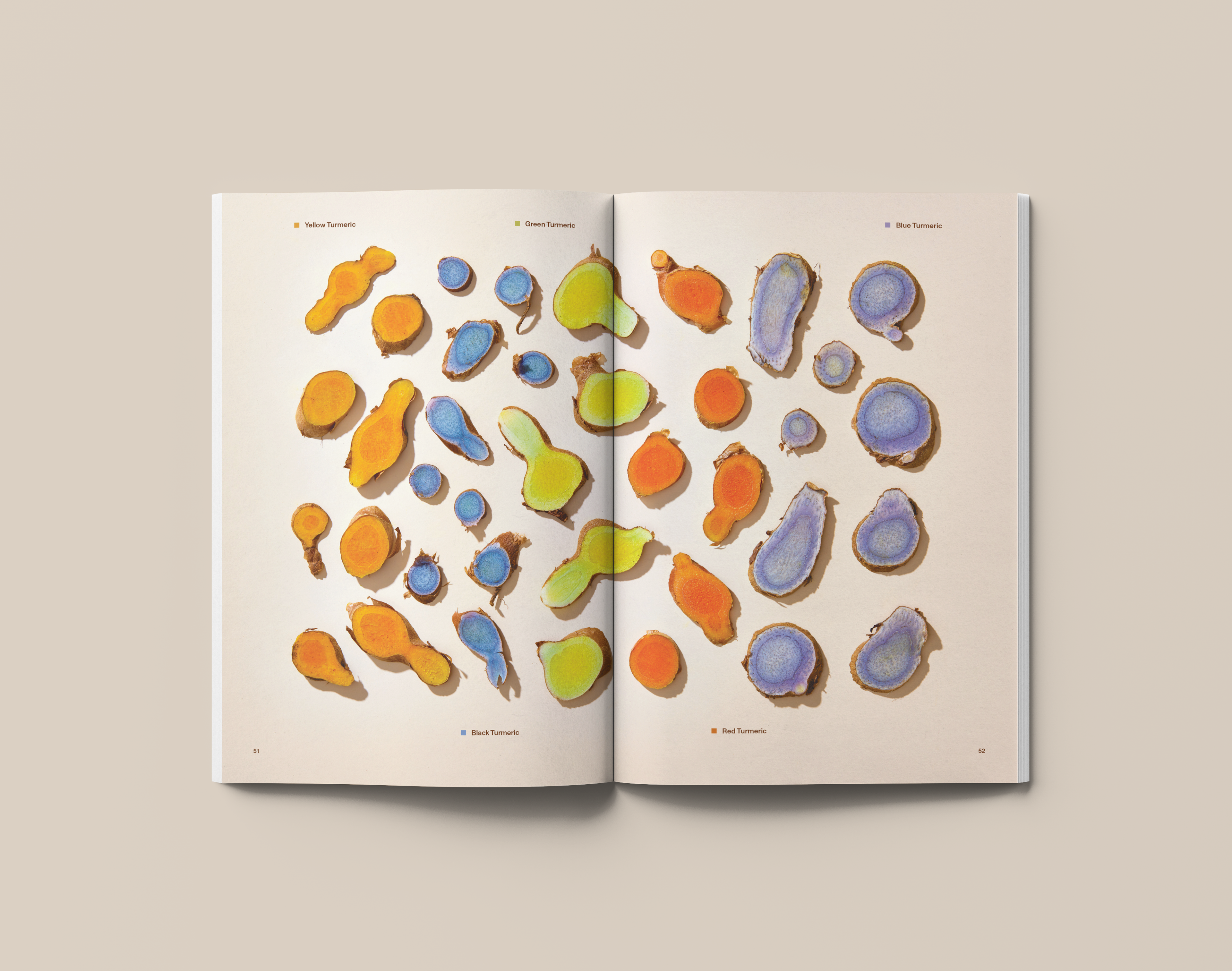

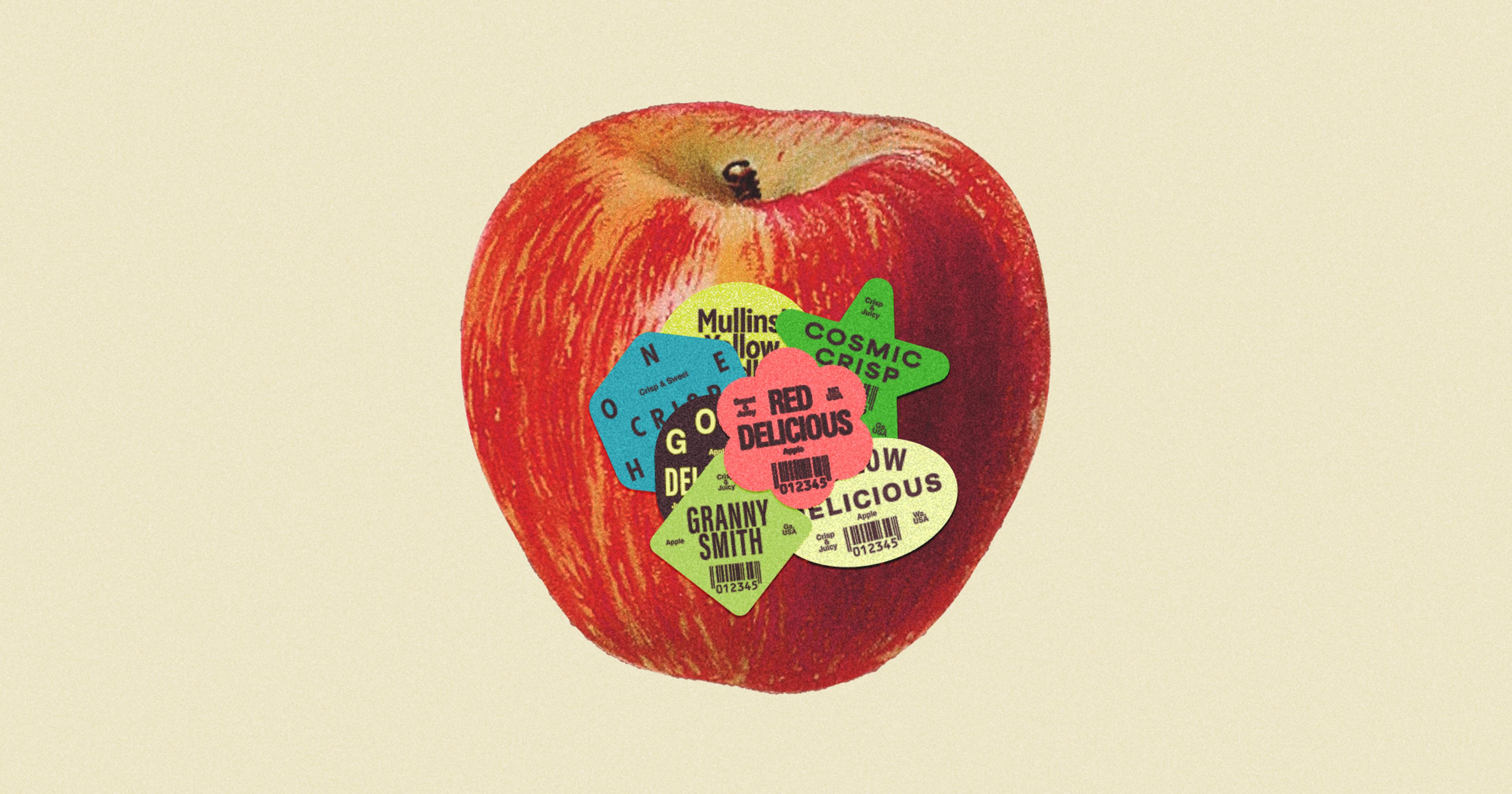

American consumers have gotten short shrift, only exposed to one flavor and color of the popular spice. The true array is dazzling.

Turmeric, such as we know it, has been reduced to powder. Whether for cultural celebrations, cosmetics, cooking, or homeopathic remedies, most people have grown accustomed to this humble rhizome in its dusty, mustard-hued form. But for the fortunate few who venture to cultivate turmeric in its natural state, a dazzling array of variety and color exists.

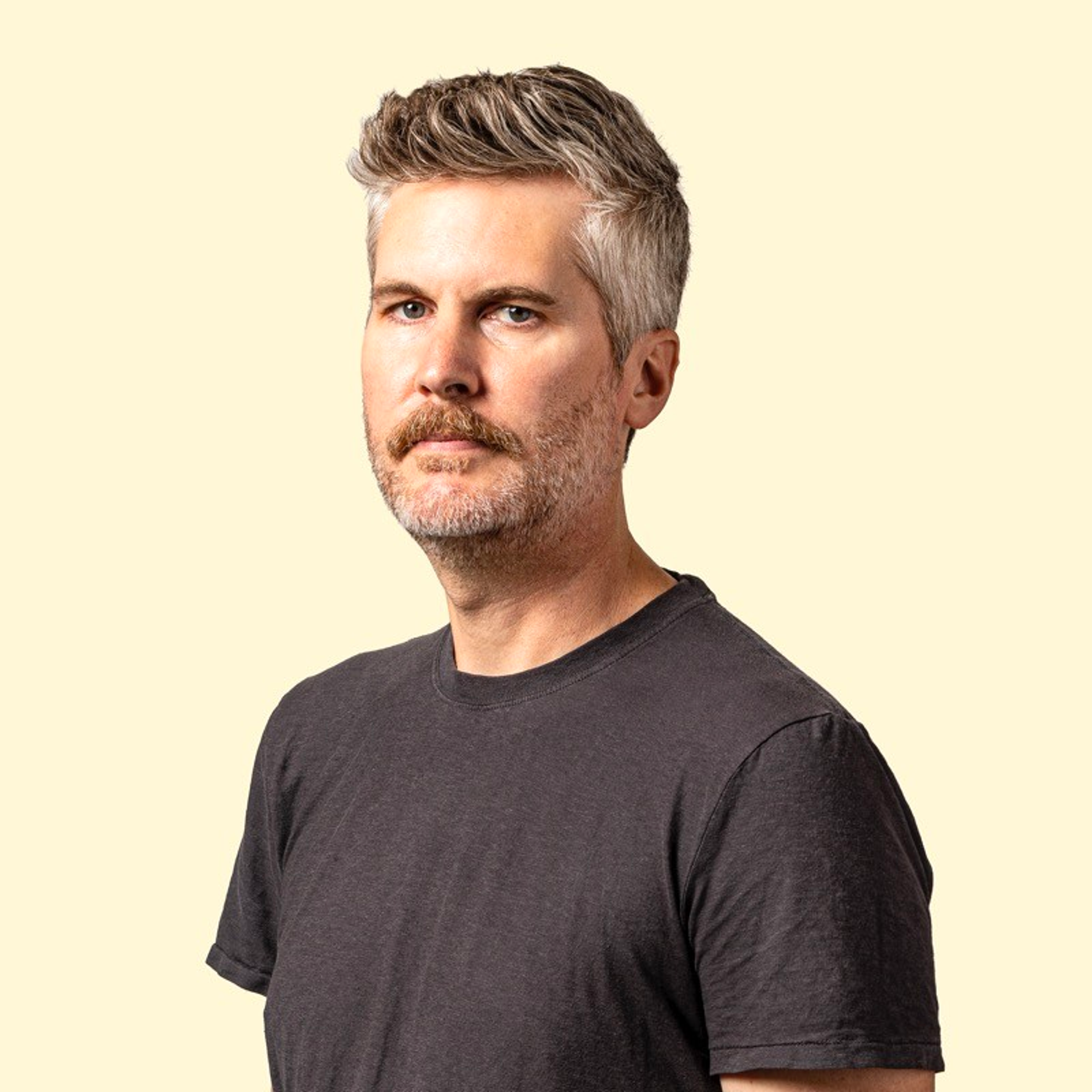

The Utopian Seed Project, a non-profit tackling climate change through crop diversification and plant migration, is unearthing the origins — and diversity — of the spice enriching your Golden Milk Latte. On a modest plot of land in North Carolina, they grow five varieties of turmeric, each with their own use, flavor profile, and color. According to director Chris Smith, the simplification of turmeric is indicative of our entire food system.

“Most crops, despite their diversity, are only represented by one or a small number of varieties or cultivars. That’s really worrying because that makes them prone to disease and collapse. But it’s also super-sad, because there’s so much diversity that exists and we, as consumers, only get to experience one of them.”

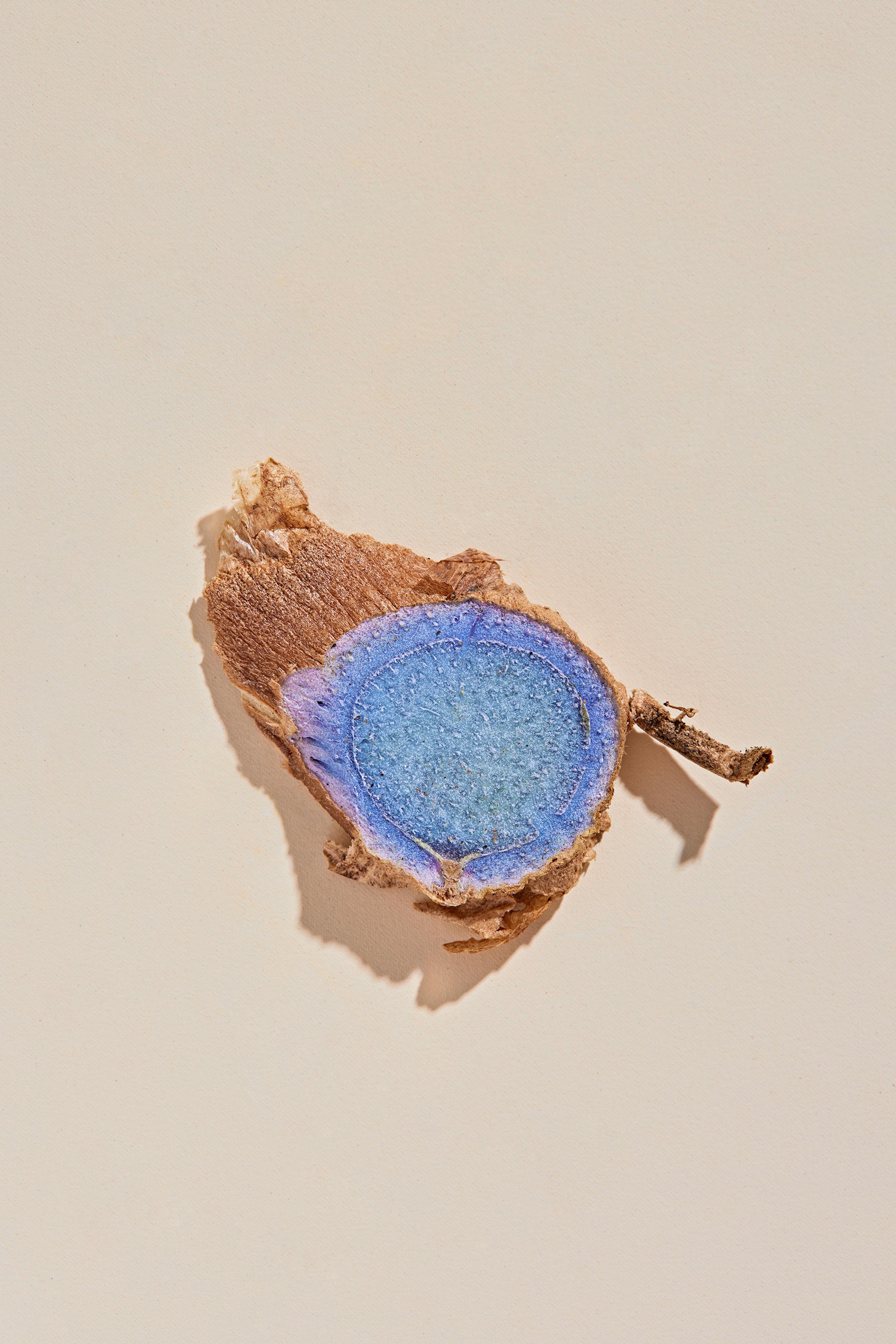

And turmeric is an experience. It comes out of the ground as a quirky, dirt-laden stem that resembles a rock with arms, but when sliced open, a mesmerizing, geode-like interior is revealed. The flesh of the red and yellow varieties bear a squash-like hue, while the more exotic black and blues evoke a watercolor of the night sky. And the green turmeric appears downright radioactive.

We sat down with Smith for some background on this dazzling visual feast.

Ambrook Research: Why aren’t people aware of how much turmeric diversity there is?

Chris Smith: Most folks only knowing and being acquainted with this one golden powder is pretty indicative of what we see across the whole global food supply. Bananas are a great example, where pretty much every banana that is eaten outside of the tropics is just one single cultivar. The same is true of turmeric. And so when we share that picture of all the different colored turmerics, it’s the same reaction as you had, Ali. It’s like, “Oh, I didn’t even know that all this existed, let alone that I was missing out on all of these things.“

AR: What are the flavor profiles for the different colors of turmeric you grow?

CS: I wish you could smell it or even taste it. The blue and the black turmeric, I describe it as a menthol type overtone. It smells and tastes way more medicinal in that regard than the yellow and the red. The green turmeric is somewhere in the middle. It’s almost got a fruitiness to it. But I’m not sure if that’s just my brain convincing me that because it’s luminescent green then it must taste something like that. And then the white mango one is interesting because that’s quite mild. I would chew on that in the field — it has kind of a citrusy light, fruity overtone to it, which is why I assume it’s called the mango turmeric.

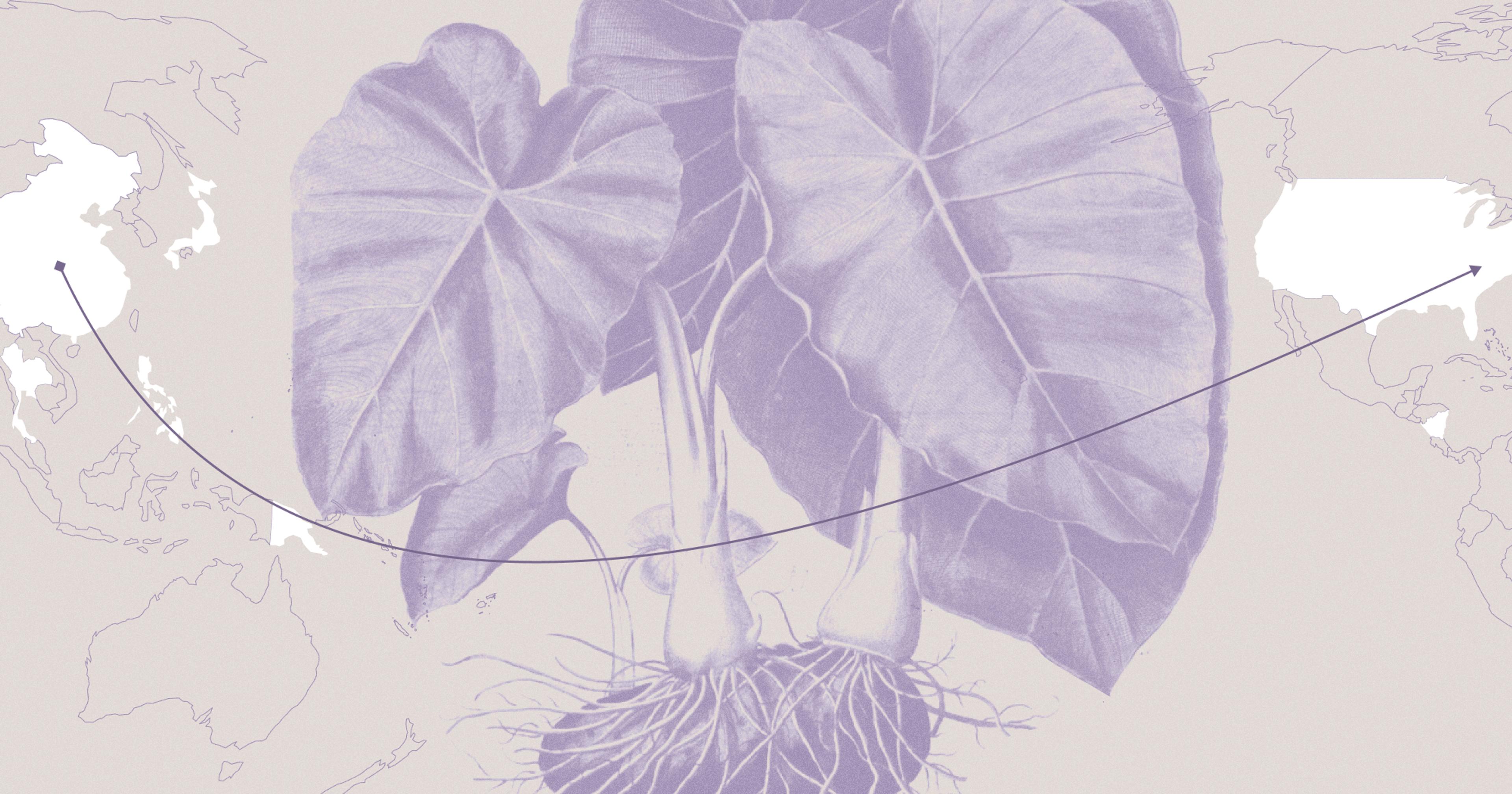

AR: What do you think has driven people to grow turmeric in North Carolina? What’s the particular appeal there?

CS: Ah, that’s a good question. I don’t know the initial personal reason why somebody was like, “I wonder if we can grow turmeric here,” but I know there were already people doing it when I first moved here 10 years ago. I think the appeal is, you know, it’s a high-value winter storage crop that’s fairly easy to grow.

There’s still a little bit of a myth that you need to grow it in a high tunnel to be successful, but we’ve been growing it in open field cultivation for years and it’s totally fine. It definitely carries a high value. And that’s certainly part of the reason people are motivated to grow it. We’ve got a pretty big herbal community and a fairly progressive food scene and I think that attracts farmers who are willing to take risks on alternative crops.

AR: It seems like turmeric cultivation already has a strong path for growth, because people are already using it for a variety of things.

CS: It’s definitely a known quantity in a way that some of the other crops have been earlier in time. Like sweet potatoes. I think they are a great example of a tropical perennial that is so adapted to our region now — it gets to a point where people don’t even think of the origins. Now it’s just like, of course we grow sweet potatoes in the South. I do think turmeric is still a little, I don’t know if exotic is the right word? It’s still got that feeling in the food system that’s like, “Ooh, you grow your own turmeric” but at some point people will just assume it’s a natural part of our food system. Everything’s on a different part of the spectrum, right?

AR: Absolutely. Thanks so much for speaking with us, Chris.

This article first appeared in the Ambrook Research Journal V. 01, a limited-edition print publication.