Forest farming opens new opportunities beneath the canopy.

“It’s not that I talk to plants. I listen to plants. It’s a difference,” said Lorri Bura. And those voices have been drawing her into the woods.

Bura’s long, white braided ponytail bobs as her feet, shod in pink Crocs, walk under the trees just steps behind her home west of Asheville, North Carolina. The house sits on about 20 acres in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains; she manages the property as Green Heart Gardens, raising medicinal plants for the tinctures and salves she sells under the Herb Mamma brand.

She still grows many herbs in the gardens’ rich flatland along Hominy Creek. But over the past decade or so, Bura has moved much of her work onto the slopes, cultivating high-value medicinals beneath the forest’s canopy.

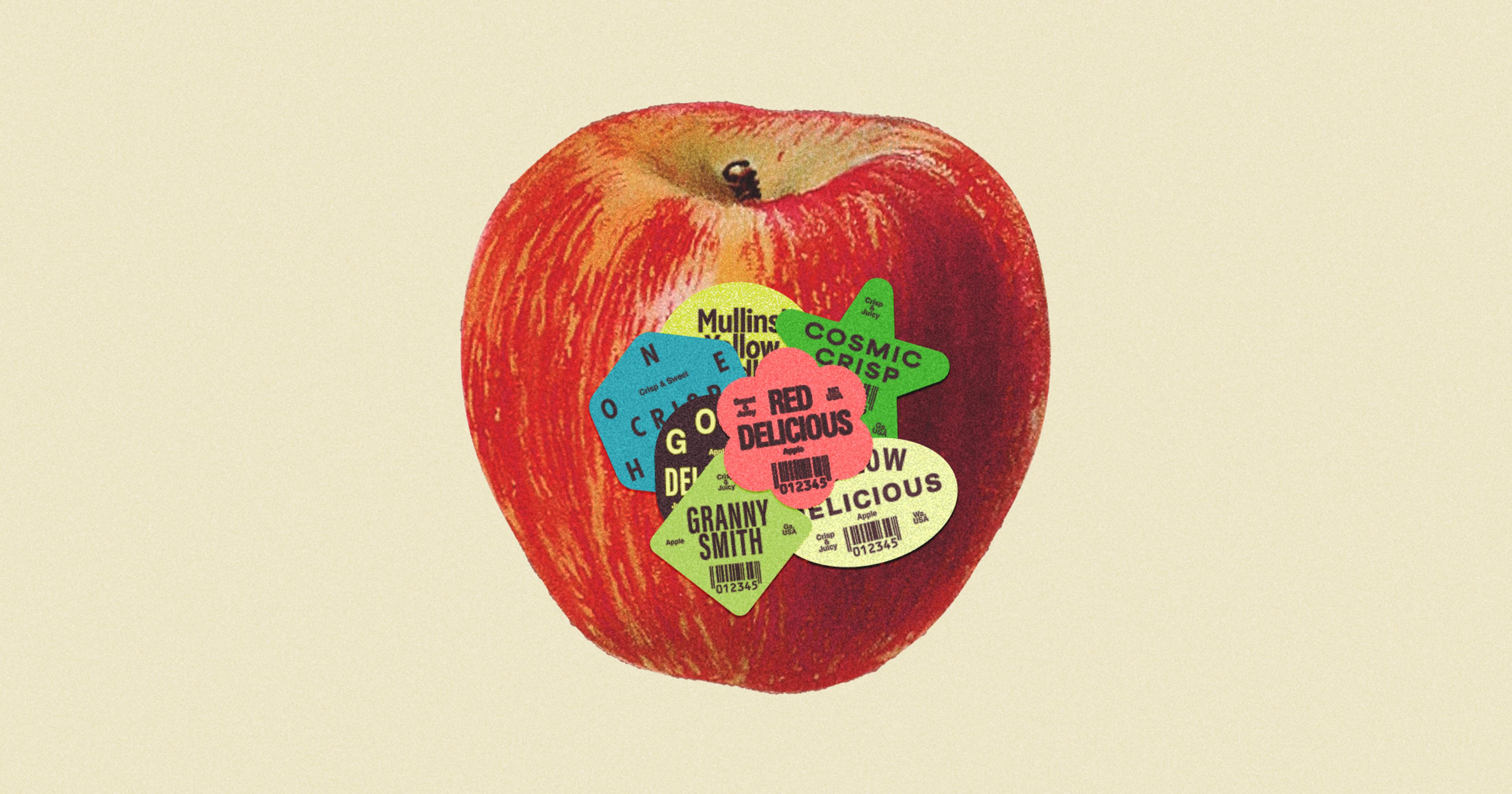

There’s Solomon’s seal, an ingredient in Bura’s popular pain-relieving salve, which she says benefits the body’s bones and connective tissues. There’s goldenseal, widely used as an immune-system booster, and wild yam, often employed to treat the symptoms of menopause. And there are dozens of seedlings of ginseng, one of Appalachia’s most highly prized herbal medicines, sold to Asian markets for hundreds of dollars per pound.

Although those plants are regularly harvested from the wild, Bura said, the approach of planting and tending them intentionally together with tree cover — forest farming — has only recently started to gain traction. She’s been leading classes and workshops as a member of the Appalachian Beginning Forest Farmer Coalition (ABFFC), a more than thousand-strong network of growers, landowners, academics, and nonprofit advocates.

Forest farming itself isn’t new, said Margaret Bloomquist, associate director at ABFFC and a horticultural researcher at North Carolina State University. Indigenous people throughout Appalachia have long tended plants under the canopy for food and medicine. Those descended from European settlers, she added, have their own tradition of growing lucrative patches of ginseng as a kind of savings account for big expenses.

As an object of study, however, forest farming hasn’t easily fit into established fields like horticulture or forestry. The ABFFC, founded in 2016 through a grant from the U.S Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, was among the first formal efforts to advise and support new growers.

“It’s kind of been at the periphery of a lot of folks’ mandates for a long time,” Bloomquist explained. “It encompasses so many people and communities and angles that it’s taken some consistent, central administrative support to bring those conversations together.”

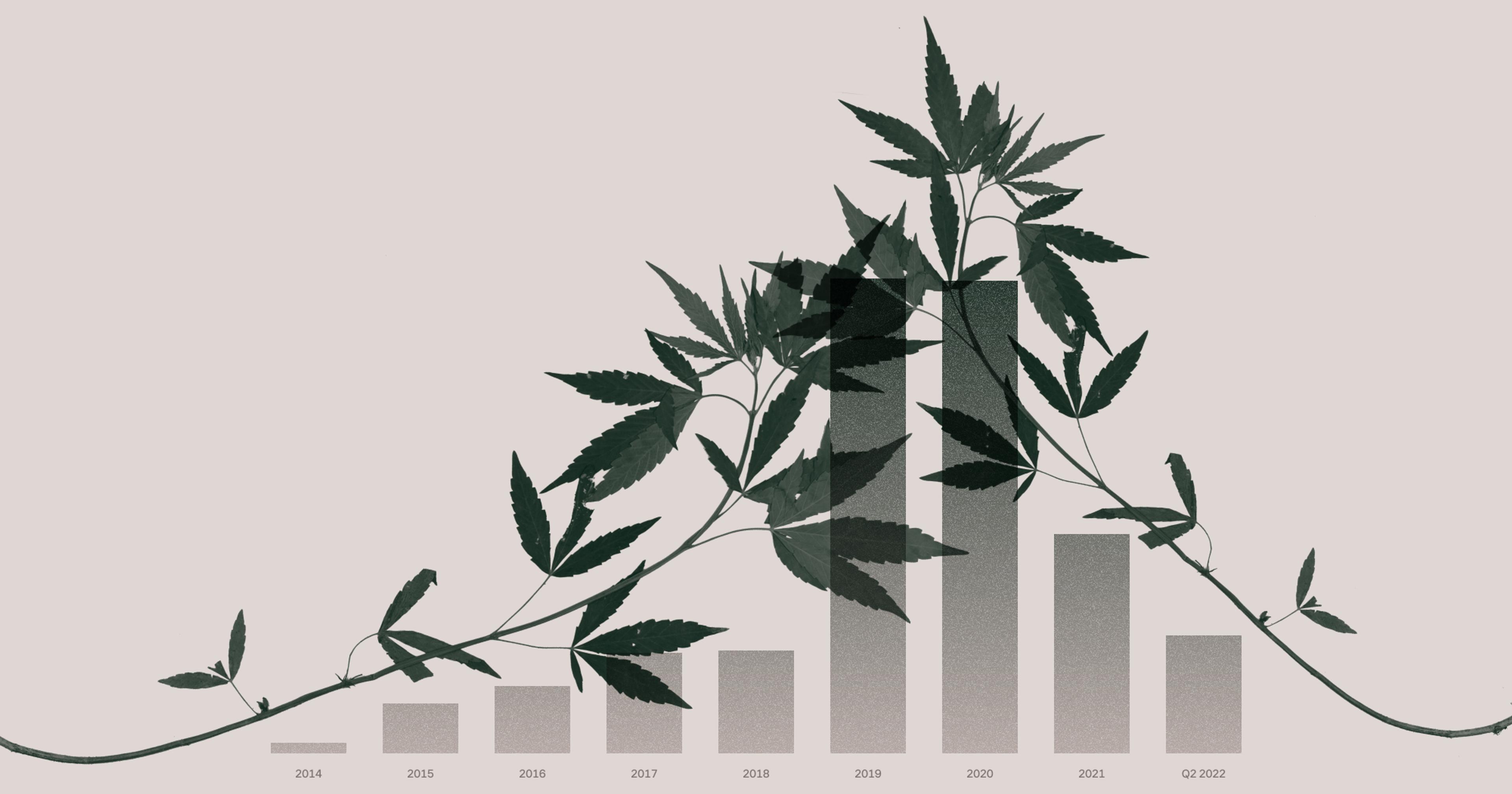

Yet with forest farming’s multidisciplinary nature comes multifaceted benefits. On the purely economic side, growers can tap into a domestic market for forest-based medicinal plant products estimated by the U.S. Forest Service in 2017 at over $1 billion annually. Bloomquist’s colleague at N.C. State, Jeanine Davis, has estimated net profits for forest-farmed ginseng and goldenseal to be as much as $40,000 and $25,000 per acre (after nine and four years of growth, respectively).

“There’s this holistic human connection to each other, to the planet, and the ability to really steward the earth in a meaningful way.”

For farmers used to annual crop cycles, the practice can provide a less stressful change of pace. Setting up growing areas in the woods can be labor-intensive, said Bura, and planting seasons tend to be very short in the early spring or fall. But once established, most forest-farmed medicinals need little maintenance beyond the occasional light weeding and scouting for disease.

And from an ecological standpoint, forest farming can help keep existing woods standing by giving landowners an income option besides timber harvest or property development. With medicinal plants in particular, Bloomquist said, there’s the potential for “conservation through cultivation.”

Wild populations of ginseng, for example, are dropping due to widespread overharvesting and are listed as endangered or vulnerable in several states. If more of the plant were grown in managed environments, those wild plants would face less pressure.

The effort to promote forest farming, Bloomquist said, is at a major turning point. The ABFFC and partners from across the country are hosting a conference next spring in Roanoke, Virginia, where they will propose a charter for an American Forest Farming Association. She said the new group will serve as a broad professional organization, with resources for marketing and economic development to help growers implement the practice.

Karam Sheban is part of the ad hoc advisory committee helping to shape the AFFA. The Yale University doctoral student leads the Northeast Forest Farmers Coalition; he said institutions outside of Appalachia have been slower to explore forest farming. When he arrived in 2018 at Yale’s forestry graduate program, the country’s oldest, the school had just begun to offer its first agroforestry class.

“There were things happening in Appalachia that were totally off the radar of institutions like Yale,” Sheban said. “And I felt like that was something that should probably be changed.”

A national effort like the AFFA, Sheban continues, could help build a community for forest farming in regions like the Pacific Northwest and Southeast that have historically had even less formal support. He believes the practice is ripe for takeoff, citing growing interest in his coalition’s mentorship program — particularly among groups that are often underrepresented in agriculture, such as younger people, women, and growers of color.

“I’ve done lots of reading and research online, but nothing beats being able to go out into the woods and actually touch and work with the plants themselves.”

Those groups also tend to have less access to land, Sheban noted; only about a third of his mentees are currently landowners. While he’d like to see more support for aspiring forest farmers to put down roots, he said many mentees are eager to apply the practice even on shared spaces like community gardens.

“In the face of climate change or economic uncertainty, I think forest farming is very empowering,” said Sheban. “It’s not that difficult to start, and it’s a way to make a positive impact on a little piece of forest land that you control, that you can feel and see.”

One obstacle to forest farming’s broader adoption, noted Lincoln University’s Raelin Kronenberg, is a lack of familiarity among those who might teach the practice. She found forest farming to be the least well-known agroforestry technique among natural resource professionals in her state of Missouri, even though it was ranked the most desirable type of land use in a survey she conducted of Missouri landowners.

To help address that issue, Kronenberg is gearing up to plant a demonstration site at Lincoln this fall, where farmers and extension agents can see how forest farming works firsthand. “I’ve done lots of reading and research online, but nothing beats being able to go out into the woods and actually touch and work with the plants themselves,” she said.

As forest farming becomes more popular, Kronenberg added, she hopes it can serve as an alternative in more ways than just producing economic value. Growing under the canopy can conserve wild plants that are rare or endangered; it can provide the raw materials for herbalists and others who practice traditional methods of healing; it can encourage a slower, smaller-scale approach to life.

“There’s this holistic human connection to each other, to the planet, and the ability to really steward the earth in a meaningful way,” Kronenberg said of forest farming. “That’s what draws me in, and I hope people can keep sight of it as it grows.”