For coastal farmers, salt hay crops offer a potential upside to seawater intrusion.

On the coast of Normandy, in Northern France, in the shadow of the ancient abbey atop Mont Saint-Michel, farmers produce a true delicacy. Flocks of sheep grazing on wide green meadows are destined to be sold as agneau de pré-salé, or “pre-salted” lamb. Thanks to the high salinity content of the coastal grasses, the meat takes on a delicate tang, impressing diners in the highest-end Parisian restaurants and fetching farmers a premium price.

Across the Atlantic, farms at the low, marshy edges of the East Coast are rapidly losing ground as rising sea levels push salty water further into the fields. American growers are beginning to see their own opportunities in reviving a historic salt hay industry.

“I have documentation of salt hay harvests on our farm dating back to the 1600s,” said John Zander, whose Cohansey Meadows Farms is perched on the Delaware Bay in Southern New Jersey. In fact, salt hay was a bustling business in South Jersey and the shores of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia from colonial times through much of the 20th century.

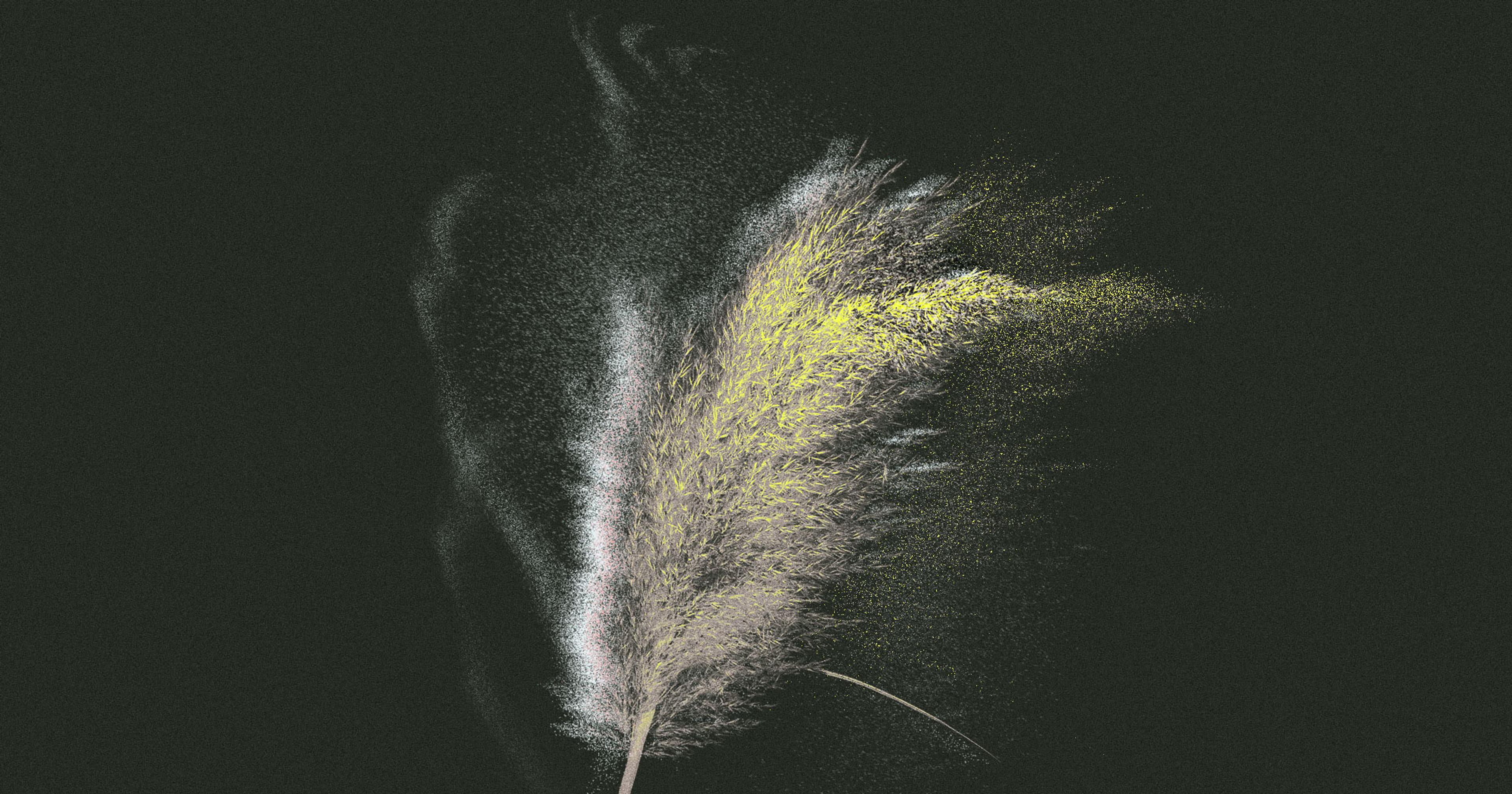

The native perennial salt meadow cordgrass — primarily a variety called Spartina patens — has historically been used not only as animal fodder, but as a building insulator and a packing material, and turned into paper and textiles. Because it’s naturally free of weed seeds, it makes an ideal mulch for berry and flower growers. Once established, it’s prolific and self-seeding, can be cut up to twice each growing season, and is essentially impervious to rot.

But by the end of the 20th century, most commercial salt hay production had ceased. It grows primarily on the muddy, marshy edges of farms, in places tough to take a tractor. For many modern landowners, that made the harvest more trouble than the crop was worth. But now, rising seas mean salt is creeping further inland, creating unfavorable conditions for most vegetables, fruits, and grains. Zander sees an opportunity: If farmers re-seed those accessible-if-salty fields with coastal grasses, they can plant and harvest the hay with modern methods, restoring the profitability and rebuilding the industry.

A 1975 New York Times article about salt hay farming “dying out” noted that the industry’s biggest boom came after World War I, when large quantities were needed to help cure concrete during federal road expansion. In World War II, it was used in the construction of runways and military structures.

“If you search enough, you can find all these weird little uses for it,” said Scott Snell, an agronomist at the Cape May Plant Materials Center. “One of the stranger ones I’ve heard is insulation for ice houses. I’ve found that there were about 30 producers in southern New Jersey, harvesting 14,000 acres annually, in the mid-1970s. We’re not anywhere near those numbers today.”

By the latter half of the 20th century, salt hay farming was virtually disappearing because of one major drawback: It’s incredibly easy to grow, but equally difficult to harvest. It performs best in marshy areas close to the water, which meant farmers had to cut it by hand, using horses and oxen to haul it out, or loading it onto rafts. By 1945, tractors had officially overtaken horsepower on American farms, and marshes and machinery don’t mix.

Once established, salt hay is prolific and self-seeding, can be cut up to twice each growing season, and is essentially impervious to rot.

“The problem is getting to it,” said Zander. “Years ago, you didn’t have to worry about sinking a tractor in the mud. But once tractors came about, the best time to cut it was when you got a hard freeze over the wintertime. That really doesn’t happen as often anymore: The last time I can remember a good solid freeze was 2018. When you get weeks of single digit temperatures, you can get out there and run a tractor and cut the salt hay really easily. In the spring, summer and fall, it’s kind of like just forget about it.”

But things are changing as saltwater intrusion renders more fields unsuitable for crops like corn and soy. High soil salinity can decrease yields, dehydrate plants, and create nutrient imbalances. A study published last year found that on the Delmarva Peninsula, just across the Delaware Bay from Zander’s Cohansey Meadows, visible salt patches almost doubled between 2011 and 2017. In Maryland, the researchers noted that by the end of that period, 93 percent more farmland was located within 200 meters of a salt patch. And though their observations were limited to the peninsula, the researchers wrote, “Our method is transferable to other regions across and beyond the mid-Atlantic with similar saltwater intrusion issues, such as Georgia and the Carolinas.”

The result on the ground in New Jersey, explained Snell, is that farmers are finding themselves with fields further from the shore, on land firm enough to drive over, but with soil now too salty to grow most things well. “It’s still farmable land,” he said. “They can still get their equipment out there and do all the work. But the traditional crops have too high a mortality rate, or production is just so far down due to the salt, it makes it not worthwhile. That’s where the opportunity lies to produce a salt-tolerant crop.”

Like, for instance, salt hay.

For the last few years, Zander has been experimenting with different planting, propagation, and harvesting methods for salt hay. His fields, planted just a bit further inland than the grasses might typically grow, are producing prolifically. He’s recently been able to expand the operation, thanks to a USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service grant. He cuts, bales, and sells some for mulch, bedding, and fodder, and he hopes increased supply will help reinvigorate the various markets for salt hay. But his main goal is to sell transplants to other coastal farmers.

“We’re cutting it out now like basically rolls of sod,” he said. “We either cut it into plugs or leave it in bigger mats, and it can be transplanted that way.”

The objective is twofold: to provide farmers with a way to maintain profitability in their newly salty fields, and to improve coastal vegetative barriers that could help mitigate worsening seawater intrusion.

“Salt hay helps to prevent runoff and erosion, so you’re capturing nutrients and reducing soil loss from wind and water erosion.”

“These salt meadow cordgrasses are natural buffers,” said Snell. “They help to prevent runoff and erosion, so you’re capturing nutrients and reducing soil loss from wind and water erosion.”

Indeed, added Zander, few things work better to hold a coastline in place. “The root mass is just so dense and thick,” he said. “It just really grips on. I think if we can get some of that into places where we’re having erosion problems, it might be pretty beneficial to some of these coastal farms and towns.”

At the Plant Materials Center, Snell said, the scientists are nearing the end of a three-year study of different varieties of salt meadow cordgrass, looking at biomass production potential and forage quality. The preliminary results, said Snell, lend quite a bit of credence to the idea that salt hay could become a thriving industry again, and offer a significant solution to farmers whose bottom lines have already been affected by sea level rise and salt intrusion.

On his quiet farm on the bay, Zander is working to build up enough salt hay acreage to satisfy what he considers to be inevitable future demand from farms all along the eastern seaboard. Salt hay may be part of his farm’s past, but it’s also, as he sees it, the only way to sustain it in a saltier future.

While his immediate goal is to get other coastal farmers growing cordgrass, part of Zander’s longer-term plan is to re-establish local salt hay fodder markets. Historically, livestock owners in the mid-Atlantic grazed their cattle in the marshes, and “pre-salted” beef — à la France’s distinctively flavored lamb — could just become the next big regional delicacy.

“For me to be able to both restore some economic production at my farm, and also be able to make an impact elsewhere, it was a real light bulb and a very rewarding moment for me,” he said. “I was recently at the New Jersey Agriculture and Climate Summit, and one of the speakers was talking about sea level rise with a projected map along the Delaware Bay. He said, kind of in jest, ‘What are these farmers going to do? Switch over to salt hay like they did in colonial times?’ I felt like standing up on my chair and yelling, ‘Yes! That’s exactly what we’re going to do.‘”