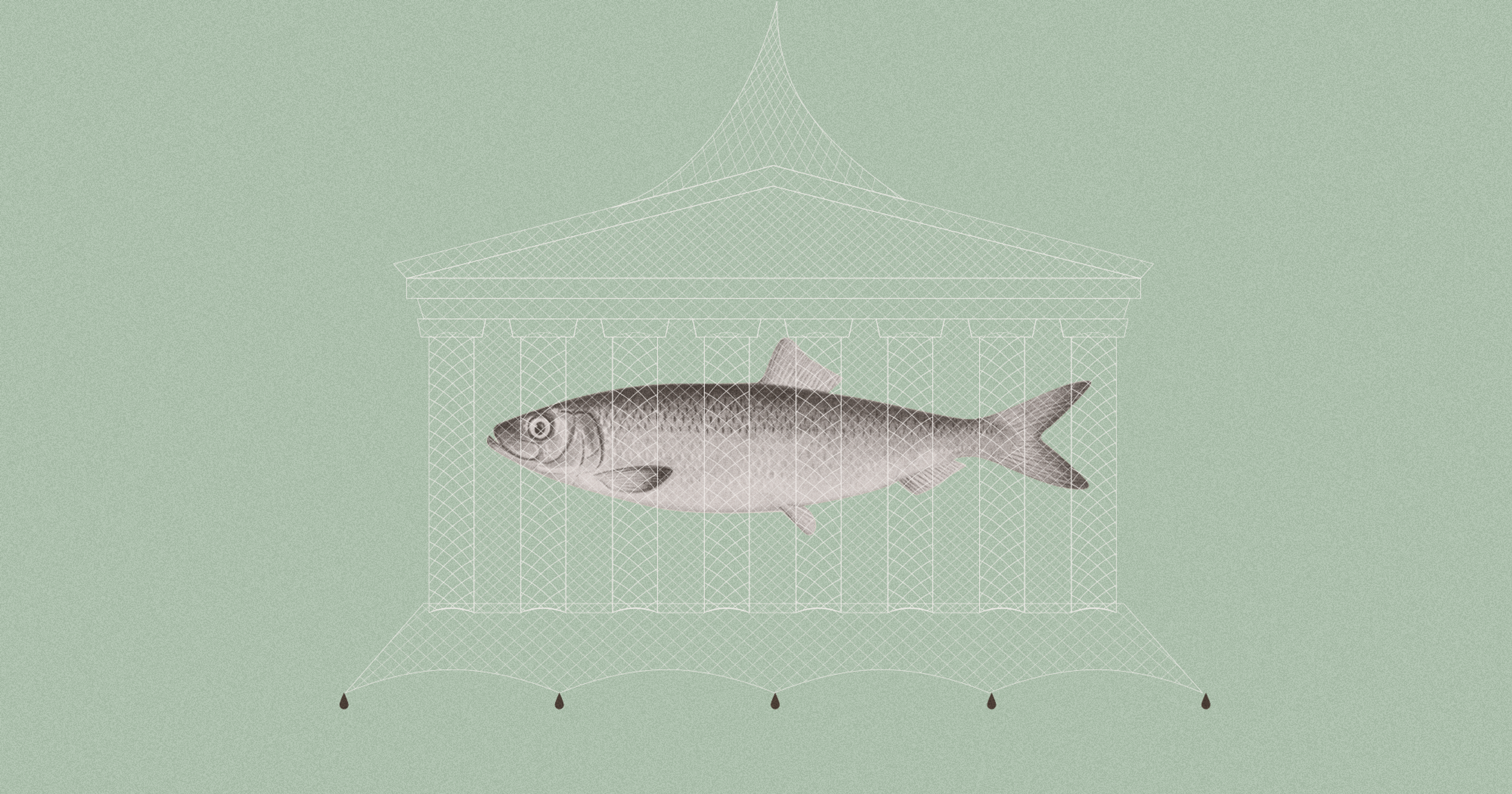

One of the most destructive forces in Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay also happens to be delicious. Why can’t we simply eat our way through the crisis?

If Holly Buckler, a commercial waterwoman based in Maryland’s Patuxent River wanted to, she could go out on the water right now and catch hundreds of pounds of blue catfish. In fact, she’s confident she could catch 2,000 to 3,000 pounds each and every day and not even make a dent in Chesapeake Bay’s population.

The problem is that blue catfish are so pervasive, their supply often eclipses their demand. She could catch all of those fish, but be stuck with nowhere to sell them, or nowhere to sell them at a fair price. When Buckler’s commercial processor becomes flooded with product, for example, the price per pound of blue catfish sags until the fishery shuts down completely to process the stock.

One day when Buckler was stuck with catfish to offload and nowhere to sell them, local restaurants reached out and said that they were happy to buy them directly so long as she could process them herself — no one wanted to puncture the pesky, ill-tasting mud vein.

While fileting fish one by one, Butler decided to slice open the bellies of a few just to see what they happened to be eating. In their guts she found American eels, broken oyster shells, and crabs.

“Blue catfish are generalists, they feed on just about anything they can get their mouths around,” said Bruce Vogt, the Ecosystem Science and Synthesis Manager in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Chesapeake Bay Office and a member of the Invasive Catfish Workgroup.

That means that clams, mussels, American shad, blueback herring, and other species that NOAA are actively trying to recover from population decline, according to Vogt, are also threatened by voracious blue catfish. Furthermore, there’s evidence that blue catfish are preying or occupying the core habitats of eel, as Buckler saw in her dissection, and Atlantic sturgeon.

The problem isn’t that the fish are eating any one species — it’s that they are threatening the entire balance of the ecosystem.

Blue catfish were introduced into the James, York, and Rappahannock Rivers in Virginia by recreational fishermen in the 1970s. Since then, their population has exploded across the Chesapeake Bay with profound effects — they’re large, apex predators with robust appetites and a knack for rapid reproduction. Between 2012 and 2022, the harvest rates for blue catfish rose 287 percent. Meanwhile, the harvest yield for more profitable fish like yellow perch, striped bass, and American eel are on the decline.

The problem isn’t that the fish are eating any one species — it’s that they are threatening the entire balance of the ecosystem.

The blue catfish invasion has gotten so bad that in 2023 politicians in Maryland sent a letter requesting federal funding to incentivize fishermen to solely hunt blue catfish, along with marketing dollars to sell the catch to consumers.

“In areas where blue catfish have been established in the Bay, they comprise up to 75 percent of the total fish weight in that tributary … As this situation continues to evolve, it is becoming more clear that economic relief for our fishing communities is needed as they work to transition from fishing on native species to targeting invasive animals,” wrote Maryland Governor Wes Moore in his plea to the U.S. Department of Commerce.

But with a seemingly endless stock of low-cost, delicious fish swimming throughout the Chesapeake Bay for commercial and recreational anglers alike to catch, a pesky question emerges: Why can’t Marylanders and Virginians eat their way back into a balanced Chesapeake Bay? What’s stopping people from eating more catfish?

Buckler has been fishing blue catfish with her husband for the past six years, though they originally focused on catching striped bass and white perch. That changed when they noticed massive blue catfish had started tearing apart their $300 to $400 specialty nets. The writing was on the wall, and Buckler figured if she couldn’t beat the blue catfish, she would shift her business and harvest them instead. She started employing trotlines and gillnets to zero in on the largest catfish.

Buckler said that she can typically get between 80 to 90 cents per pound on blue catfish, so a 20-pound fish will net her about $17. But when the market is nearing a shutdown, the price plummets to 55 cents per pound and that same fish will bring in only $11. When the price gets too low, it’s simply not worth the effort for commercial fishers like Buckler to go out on the water.

“Right now blue catfish are cheaper than other protein options … We need to communicate its value as a food source.”

As a recent example, a few weeks back a wholesaler came to Buckler’s residence to pick up fish. After they were sized and scored, she received her check for the catch. For 1,298 pounds of blue catfish, she received $693. After paying for gas to run both her boat and to power her truck to haul them, she had netted less than $300 for more than half a ton of product.

“It’s not fair. Grocery stores are selling filets at $12.99 a lb, and [you can get] four to five pounds of filets off a 25 to 30 pound fish. The grocery stores and wholesalers are making out and us as the little guys, we’re getting screwed,” she said.

Buckler said grocers should consider stocking only wild catfish instead of farm-raised. But according to butchers she’s spoken with, visual appeal is the issue . Farm-raised catfish is pinkish, while wild-caught is pale and white.

Beyond getting more wild blue catfish into grocery stores, people simply need to be eating more of it. The challenge, both Buckler and Vogt say, is that catfish have a mixed reputation due to their mud vein, also called a mud line.

If someone cuts the mud vein while butchering filets, the fish will taste, well, muddy. But if they don’t, the flavor is light, crisp, and extremely versatile. Vogt points to local initiatives, like schools making fried fish cakes and feeding them to students, as a means to introduce the fish at an early age. Plus, there are clear economic benefits to blue catfish as a protein source in the face of sticky inflation.

“We will not get rid of every catfish. They’re here, we’re not going to eradicate them, and there will always be negative consequences.“

“Right now [blue catfish] are cheaper than other [protein] options … We need to communicate its value as a food source,” said Vogt. “Chefs have picked up on it [and we] see it more in restaurants, but still there is work to do.”

But even with more fishermen on the water hunting catfish, Vogt isn’t confident that that there are enough people — or processors — to target the rampant population. If the population were to reach crisis levels without a market for human consumption, the next steps would be to process the fish for pet food, compost it, export it to China and elsewhere, or simply throw it away, which is clearly not ideal.

“The focus has been making sure a product comes out of removal,” Vogt said.

Even so, the casual introduction of a blue catfish by an angler half a century ago will more than likely have repercussions for decades to come.

“We will not get rid of every catfish,” said Vogt. “They’re here, we’re not going to eradicate them, and there will always be negative consequences, but we’re moving in the right [direction] to make [it] positive.”