In Montana, hunters and other sportsmen are starting to learn the benefits of regenerative agriculture, well outside the farm.

The late summer grass crunched under my feet as I tried to keep up with my dad’s 6-foot-tall strides. Dressed in camouflage, we carried our weapons of choice — my dad, his bow, and me, my plastic tea party set (which conveniently came with a backpack).

At 4 years old, the excitement for my first hunting trip was built around the promise of a tea party with my dad. Little did I know, those trips — and the stewardship he instilled in me — would deeply shape my views of the world and the career path I would ultimately take.

Growing up a fourth-generation Montanan in a family of hunters and fishermen, it’s a no-brainer that hunting and conservation are inextricably linked — if we want wildlife to be around for future generations, we have to treat it sustainably today. We didn’t used to see agriculture as part of that equation, but over the past few years, the intersection of hunting, sustainability, and farming has come into focus for both my dad and me.

For him, it was using regenerative agriculture to transform our property into a plentiful wildlife habitat. For me, it was working at a company that’s trying to help farmers build sustainable businesses. But while I had heard about regenerative ag, it wasn’t until my dad dove in that I started hearing about it in the context of wildlife management.

In a world where most media doesn’t highlight hunters and sustainability in the same story, my dad’s path is a tangible reminder of the many ways outdoorsmen and landowners can have a real impact in enriching our natural resources and being stewards for generations to come.

How It Began

My dad’s dream was always to own a piece of land he could restore into a habitat for wild game. When he finally bought a few-hundred acre ranch in 2015, it wasn’t exactly brimming with life. Years of mismanaged grazing had decimated the plants, and the spring creeks were clogged with silt, making them essentially sterile. But my parents saw the potential.

Over the next six years, they rebuilt the creeks, created wetlands, and planted fields to provide habitat for pheasants and deer. Without a background in farming, my dad sought advice from neighbors on agriculture’s many challenges.

Katie carries some antlers earlier in life.

The first year, we had a great crop, and the second year went well too. By the third year, we saw emerging weed pressure and started spraying herbicides and using fertilizer. The weeds kept getting worse, and by 2022, the pigweed was out of control. We started the spring by spraying glyphosate to kill everything, but the weeds kept coming back before the crops could take hold.

My dad was at his breaking point when Kate Vogel of the seed and agronomy consulting firm North 40 Ag suggested he check out Montana’s first regenerative agriculture symposium. When he asked what regenerative agriculture even was, she recommended Gabe Brown’s Dirt to Soil (which my mom now refers to as my dad’s bible), and a lightbulb went off. Regenerative agriculture made the challenges he’d had on the land — feeling like the harder he worked, the worse things got — make sense.

In spring 2023, his decision to mostly stop spraying herbicides and tilling and start planting cover crops was relatively easy, in part because my dad was fortunate to not have to deal with the same financial and generational pressures as many producers. Kate shared that for landowners considering new practices, in general, “If they’re focused on wildlife, it’s easier to make that jump than if you need to make sure you get a cash crop the following year.” My dad hasn’t looked back since.

A Day in the Field

While “sustainability” can sometimes feel like a meaningless buzzword, sitting in a ranch outbuilding a little before 8 a.m. last July, surrounded by the smell of black coffee and musty wood, sustainability in the form of regenerative agriculture felt clear and practical.

We were kicking off a regenerative ag field day on our property, and our guide was Jeremy Sweeten from Understanding Ag, a regenerative consulting company founded by Gabe Brown and Allen Williams — pioneers of the soil health and adaptive grazing movements, respectively.

Our group was a mix of local farmers, ranchers, and conservationists, but they were also avid hunters, interested in whether adopting new practices could improve their land for wildlife.

Inspecting soil samples on the field day.

There was a sense that there’s an opportunity for regenerative agriculture and hunting to overlap, but also a lack of relevant information — that’s what inspired the field day. Jeremy’s own ah-ha moment came from 10 years of hunting in the West. “I’ve hunted some of the BLM ground where there’s been grazing allocations, and if there’s been livestock there, it’s grazed to the ground, and so the hunting’s horrible. I’m like, ‘There’s gotta be a better way.’”

He started by explaining that regenerative agriculture isn’t a strict list of requirements that an operation does or doesn’t meet. It’s a set of principles and practices that can help restore soil health. Healthy soil decreases the need for costly inputs like fertilizer and herbicides and makes the ecosystem more resilient to shocks like rainfall, wind, and drought. While it can require more intensive management, many find the practices make their operations more profitable.

For Understanding Ag, the six principles of soil health, described in Gabe’s book, are the fundamentals. They include knowing your operation’s context, minimizing soil disturbance, keeping the soil covered, cultivating diversity of all living species, keeping living roots in the soil year-round, and integrating livestock.

The group left the field day with concrete ideas for restoring their soil to build better wildlife habitat, and maybe even ready to share their new knowledge with others. For my dad, the fact that it took eight years of struggling before he stumbled upon regen for wildlife has made him eager to share the quantifiable impact it’s had on our property.

The Proof Is in the Antlers

After a morning of soil sampling, my dad took our group back to the outbuilding’s dimly lit attic. With a smile, he gestured to a row of plastic bins on the ground, each filled with deer antlers.

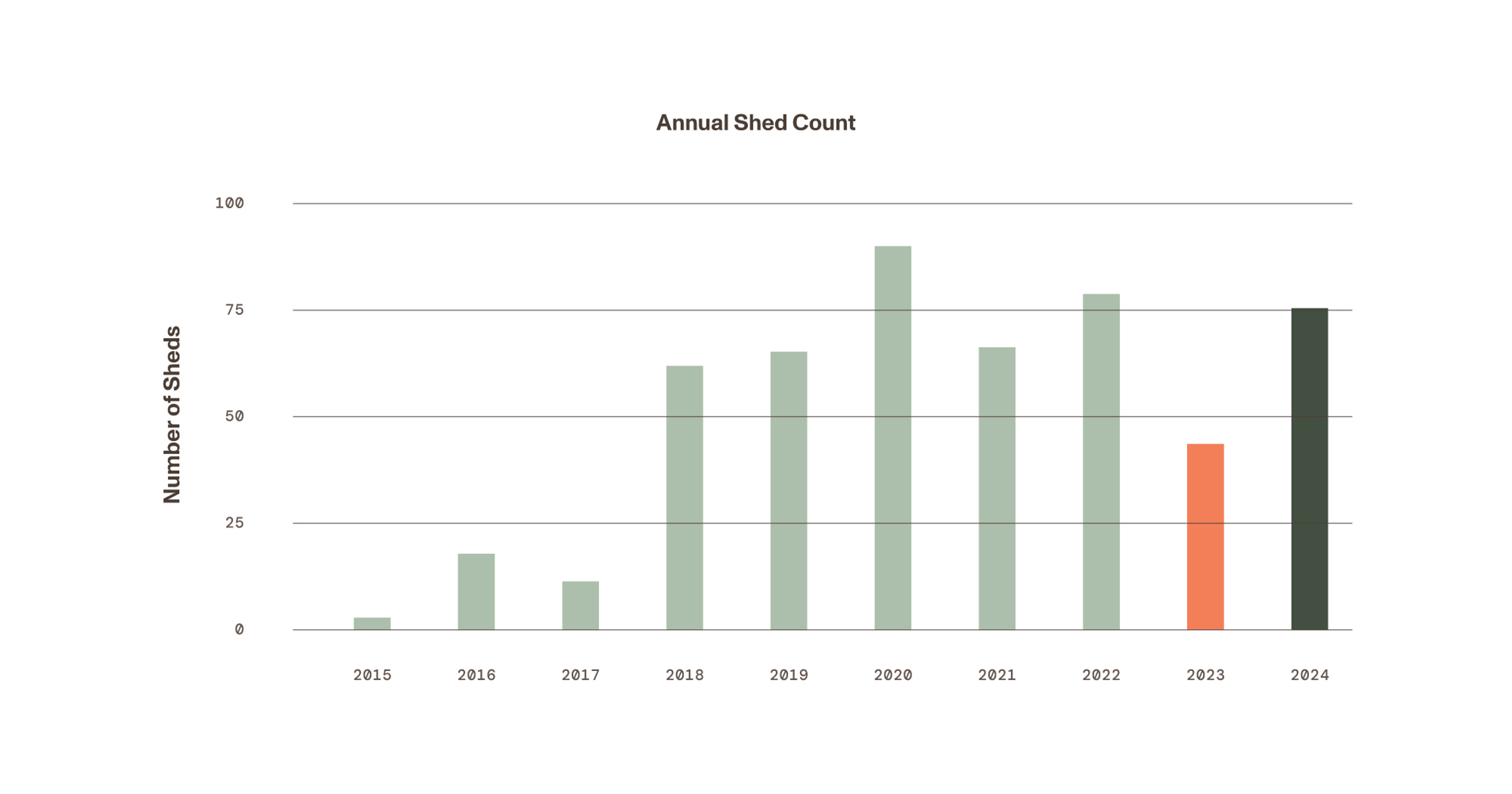

Deer shed their antlers every winter, meaning each year’s sheds offer a rough way to understand the size and number of bucks frequenting the area. My dad has counted every shed from our ranch for the last 10 years, and the story is striking.

The first year, we collected two sheds, with the biggest being a three point. The size of a male deer is often talked about in terms of the number of points on its antlers, and a three point is not big.

That number grew as we rehabilitated the land and planted crops the deer could eat throughout the winter. In 2023, the number of sheds dropped by half as a result of the previous year’s fields being sprayed twice with glyphosate and the deer having little food to help them through the winter. Since implementing regenerative practices the following spring, the number has rebounded. Last year, we found 74 sheds — up 3000% over 10 years.

2022 was the year of spraying the fields 2x and tilling them once. 2023’s sheds were the result of the lack of food in 2022, and 2024’s sheds show the results of the first year of regenerative ag.

Beyond the number of antlers, my dad has also noticed a shift in the age of the deer. We’ve sent teeth from all the deer we’ve harvested or found dead to Matson’s Laboratory for aging. In the last few years, the bigger bucks have been five and a half to six and a half — very old for whitetails in Southwest Montana.

While many of them leave for the summer, they come back in the fall because they know there’ll be food for the winter. Jeremy, who implemented regenerative practices on his own property, also noticed an increase in deer, particularly ahead of big winter storms when they seek out more nutrient-dense feed in his bale-grazed fields: “It’s pretty interesting that the deer gravitate toward the areas where the management has changed.”

The first year's antler haul on the left, the most recent year on the right.

This change can’t be attributed to a single intervention, but for my dad, regenerative agriculture for wildlife just makes sense. If he can keep cover on the ground year-round, wildlife have more food and shelter to get them through the winter. If he doesn’t have to spray herbicides and use fertilizer, the chemicals won’t run off and impact the fish populations. If the soil is healthier, the plants have more nutrients, and the animals eating the plants will be healthier, bigger, and more likely to make it through the winter.

On the Birds and the Bees

When I asked my dad what he would want people to know about his experience adopting regenerative practices, he said that it’s not just about shooting a big deer: It’s about building a resilient ecosystem.

When we bought the property, there were no turkeys. Now, you’ll see groups of 10 or more shuffling across the road. The butterflies came back with the planting of pollinator mixes, and the fields literally buzz with bees. Ten years ago, there were no fish spawning in the spring creeks. Last month, my dad counted over 300 redds (spawning beds where trout lay their eggs) in one creek alone.

The author and her dad.

Beyond seeing the change in the biology of our property, the most persuasive thing for him has been comparing the time, money, and effort he was spending before and after. It certainly takes work, but regenerative ag has meant spending less time and money on things like spraying weeds and still seeing better results. It’s also been a lot more fun.

For me, as I’ve talked to more farmers and ranchers who have adopted regenerative practices, I see my dad’s story as a version of a broader narrative of landowners looking to achieve their goals for the future, whether it’s becoming more profitable, leaving their land in a better place for the next generation, or cultivating a place for outdoor recreation and wildlife.

And to anyone still skeptical about trying regenerative agriculture for wildlife, there’s an open invitation from my dad to come see it for yourself (just don’t take the antlers home with you).