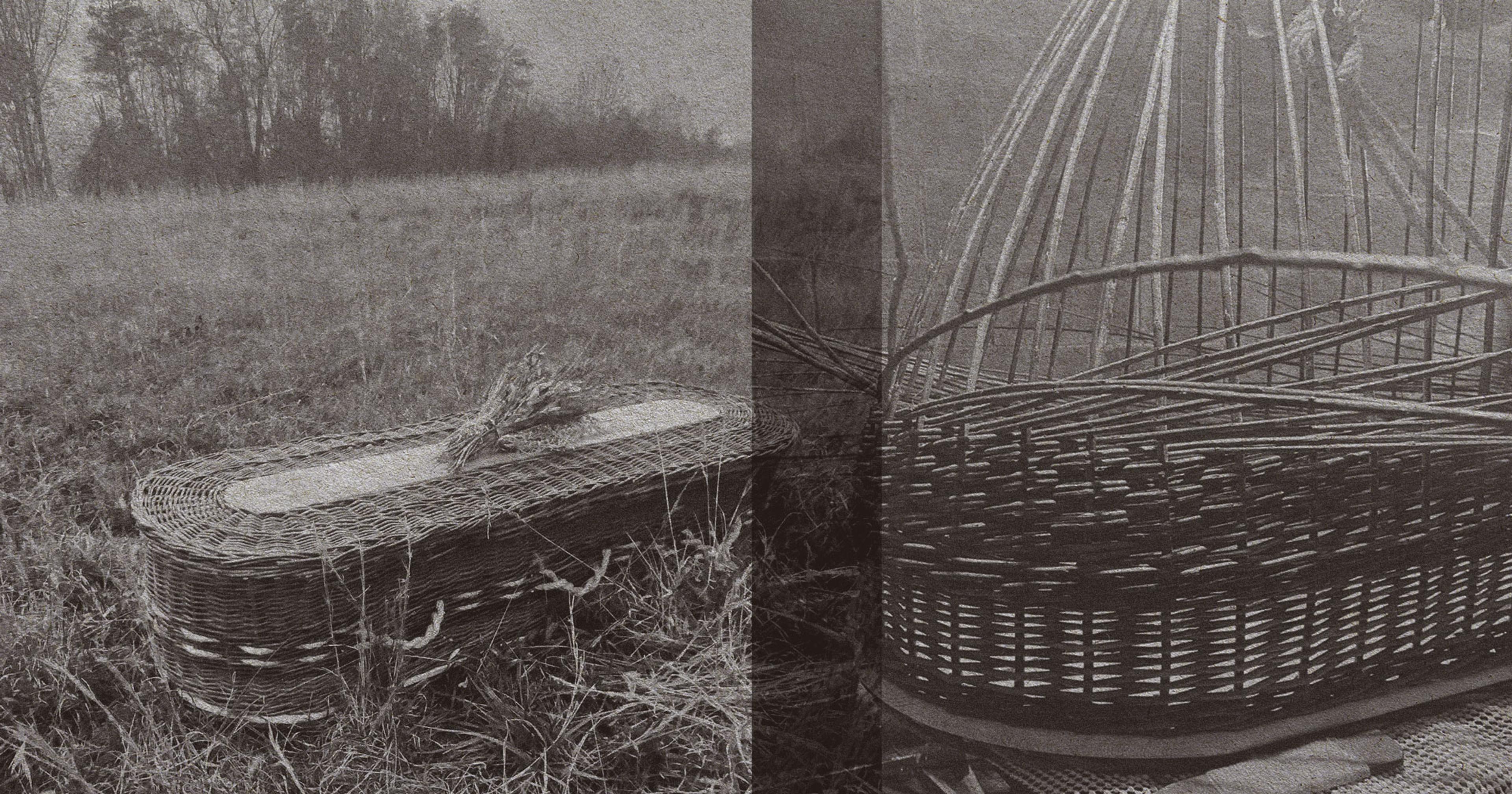

As environmentally friendly green burials become more popular, so too are the biodegradable willow caskets grown and woven by dedicated craftswomen.

Sarah Lasswell initially planted willow in 2018 to prevent erosion in one of the bottom fields of her North Carolina flower farm, Moss & Thistle. A year later, however, she came across an image of a woven willow casket on social media. “Gobsmacked” is how she described her reaction. “That saying goodbye to someone could be done in such a beautiful, loving, natural way was just a revelation,” she said. “From that point, I started looking into green burial.”

The Green Burial Council defines green burial as “a way of caring for the dead with minimal environmental impact that aids in the conservation of natural resources, reduction of carbon emissions, protection of worker health, and the restoration and/or preservation of habitat.” (In the absence of state or national laws defining green burial, the GBC’s standards are widely used.)

At a minimum, this means green burials must inter unembalmed bodies in biodegradable containers, in plots without concrete vaults. According to New Hampshire Funeral Resources, Education, and Advocacy, 418 cemeteries currently offer green burials in the United States and Canada. These include hybrid cemeteries that blend conventional and green burial sections, natural cemeteries containing only green burials, and conservation cemeteries — nature reserves held by a conservancy or land trust that contain burial grounds.

As more people become aware of the option, green burials are having a moment. According to a 2023 report by the National Funeral Directors Association, 60 percent of consumers expressed interest in the practice. Many are drawn to its environmental benefit; the GBC estimates that green burials sequester 25 lbs of carbon as bodies release nitrogen and other nutrients into the soil through decomposition. In comparison, conventional vault burial emits as much as 250 lbs of carbon per person, with cremation ranging between 250 lbs to 540 lbs.

Once Lasswell realized she wanted to weave willow caskets in 2019, she reached out to Carolina Memorial Sanctuary in Mills River, North Carolina, a conservation cemetery within 60 miles of her farm. l. They were thrilled. At the time, Lasswell said, there were only two weavers selling willow caskets in the country: Mary Fraser in Turners Falls, Massachusetts, and Maureen Walrath in Port Townsend, Washington.

Through their work, Fraser, Lasswell, and Walrath lower green burial’s carbon footprint even. Whenever possible, they grow or wildcraft their own willow. They weave their vessels for local populations, lessening the need for imported biodegradable caskets. For Lasswell, it was the willow casket that brought her to green burials, and it is the plants, the creations she makes from them, and the connections she makes with those grieving that keep her inspired.

Green burial, she said, “offers so much for the person being buried, for the family saying goodbye, for the community surrounding the cemetery, for the very earth itself.”

Communing With Ancestors, Forging New Bonds

For Fraser, it took a trip to her ancestral homeland of the United Kingdom to encounter her first woven burial vessel. Immediately taken with it, she made her way to northeast Scotland to train under weaver Karen Collins.

Walrath, too, journeyed to the land of her ancestors — Ireland this time — to learn the art. As she was weaving her first coffin, she later learned, her grandmother — whom she never met due to her father being adopted — died in Germany. “It became this spirit vessel for her,” Walrath, an interdisciplinary artist, said of the coffin. When she weaves, she feels connected to a “lineage that goes back and back and back into generations that I can’t even touch or remember but can feel through working with the willow.”

Lasswell also planned to journey to the British Isles to learn casket weaving; when the pandemic scuttled her plans, she instead reached out to Fraser. Though she had resisted teaching coffin weaving before, Fraser made an exception for Lasswell and one other woman.After quarantining, all three women gathered for two intensive weeks in Vermont in the fall of 2020. This past April, she taught Michael Schofield, a farmer and weaver in southern Michigan, how to make coffins, urns, and burial trays for shrouded bodies.

“I am hoping that we’ll greatly increase the coffin weaving community in the next few years around the country, so it’s more accessible, and people can support a local economy and not be buying imported coffins,” said Fraser.

Cultivating Willow

“Every stick is precious,” Walrath said, contemplating a bundle of sticks harvested last year in her studio. “Every one has been touched and cut by hand and bundled and touched again and sorted by size.”

“Willow is an amazing plant,” agreed Lasswell. Compared to flowers, which need harvesting daily or every other day, willow is also incredibly low-maintenance. “You plant by cuttings, and the cuttings take four to five years to reach maturity. You harvest it every single year while it’s dormant. And that’s it,” explained Lasswell. She has approximately 4,000 plants on a half acre, with plans to expand to a full acre. A pond provides gravity-fed irrigation, and neem oil and the soil bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis eliminate pests. Lasswell has also interplanted clover as a cover crop, which she flails regularly so that the clippings decompose and return nitrogen to the soil.

Planting her own willow also helps keep weaving economically viable, as the crop is in high demand and short supply. Only two main sellers exist: Living Willow Farm in Ohio, and Appalachian Willows & Brooms in West Virginia. For dried willow, prices range from $12 to $15 per pound. Cuttings, Lasswell said, can be $2 each, sometimes more.

Fraser currently sources the estimated 400 lbs of willow she uses each year from Appalachian Willows and Willow Grove Farms in southern Indiana, but she will soon have more local sources. Basketmaker Sandra Kehoe has planted 9,000 willow plants in upstate New York that Fraser will help harvest this winter, and a farm across the river from Fraser in Gill, Massachusetts, planted some last spring for her on otherwise unusable land between a field and a swamp.

Walrath has never worked with commercially grown willow. Instead she has wildcrafted, or foraged, wherever she has lived, including Oregon, the Hudson Valley, and Missouri. Even when she was visiting her hometown of Chicago, she found mowed sandbar and coyote willow beneath power lines near Joliet and Channahon, Illinois, on the edge of a road near an oil refinery.

At her current home on the Olympic Peninsula, she both wildcrafts and tends a patch planted five years ago using cuttings she received from other weavers and growers. “My practice has been strengthening along with the willow patch, and so it’s just been something that I’ve allowed to grow along with the willow,” she said.

Returning to the Earth

In Cedar Grove, a rural town in the Piedmont of North Carolina, sits the 87 acres of Bluestem, a nature preserve and cemetery run by co-founders, co-directors, and friends Heidi Hannapel and Jeff Masten. Veterans of the conservation movement, Hannapel and Masten decided to found Bluestem after each had helped a parent die peacefully at home. “What we’re doing is actually reclaiming an old tradition,” said Masten. “We’re providing an alternative to what’s currently readily available as a burial option.”

They purchased the land from a farmer whose family had owned it for more than a century; the presence of a family cemetery on the property was a crucial icebreaker, said Masten. Having worked in farmland conservation, he was sensitive to any suggestion that the project was taking away good farmland, especially since the farmer and his kin own the surrounding land.

Masten was therefore pleased to see the benefits Bluestem has brought to the ecosystem. Besides the carbon sequestration of the burials, he estimates that millions of pollinators have been attracted to the reserve’s native plants and then visit surrounding crops. Bluestem — named for the prairie grass they have planted to help restore the early successional grassland habitat — has also become a haven for birds, with birders having spotted over 133 species.

“The former landowner will drop in now and then, and he’ll want the latest statistics,” said Hannapel. She also regularly sends texts and Instagram updates to the farmer’s niece, herself a fifth-generation farmer who owns 40 adjacent acres, currently used for hay. “We’re building trust,” Hannapel explained.

Building trust is important not only with the farmers but also the families that bury their loved ones at Bluestem. Lasswell noted that commercial funeral homes are increasingly trying to capitalize on the success of green burial, whether or not they embrace or understand the principles behind it. Just last week, 189 improperly stored bodies were removed from a funeral home in Penrose, Colorado, that advertised green burials. (Notably, Colorado is the only state in the nation that does not require any license or certification to open a funeral home.)

“It’s even more reason why our values are so important,” Masten said when asked about the Colorado incident. “Economics are part of the equation, but we’re not driven by it. We’re driven by values. And I think that’s a difference between how many businesses operate.”

The Power of Community

An often overlooked benefit of green burials that everyone interviewed mentioned is how the process builds and strengthens community. Even though Bluestem only opened in November of last year, they have already matched their projections for their fourth year of operations with 25 burials and over 1,000 visitors. “It’s affirming to our vision, that there is a hunger within the community for this alternative,” said Masten.

On their end, Fraser, Lasswell, and Walrath are starting a weaver’s guild so that they can promote the craft and ensure that people looking for woven vessels can connect with the nearest weaver. Walrath is also on a local board hoping to create a conservation burial ground that not only includes indigenous communities in the decision-making process but also offers them no-cost burials.

Fraser and Lasswell also invite people to help weave. “That time between a death and a burial, you’ve got this few days where you often feel very helpless,” said Lasswell. “It’s very meditative. It’s quiet, it’s tactile, it’s beautiful.” Some people have woven their own caskets — and use them in the meantime as storage vessels, coffee tables, or even a bookshelf with removable willow shelves.

The larger the media footprint of green burials, Lasswell said, the more people can discover that this traditional way of burying loved ones is both legal — while laws vary, all states allow some form of green burial and 44 allow home burial — and accessible.

“These practices of being with our dead and dying have been systematically taken out of our hands,” said Walrath. “We have these other kinds of choices. I want people to know about their choices.”