But if we run out of water, we’re cooked.

Over the last century, temperatures across much of the United States have risen by two degrees Fahrenheit — in Alaska they’re up three — yet the Midwest has managed to skate by with just a 1.5-degree uptick. In fact, some Midwestern counties haven’t experienced any temperature rise at all.

Read Next

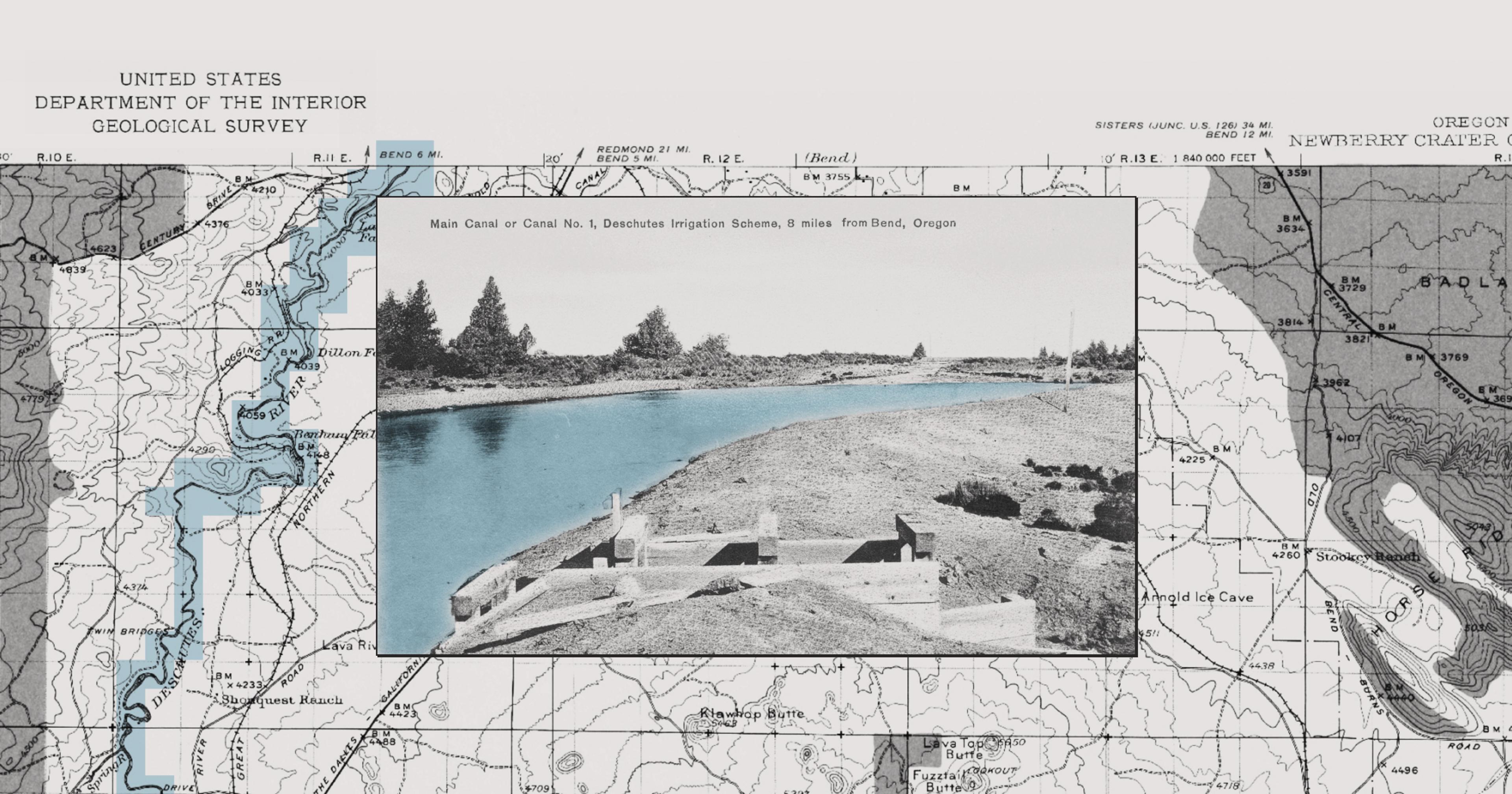

Some of Oregon’s Irrigation Systems Are More Than 100 Years Old, and It Shows

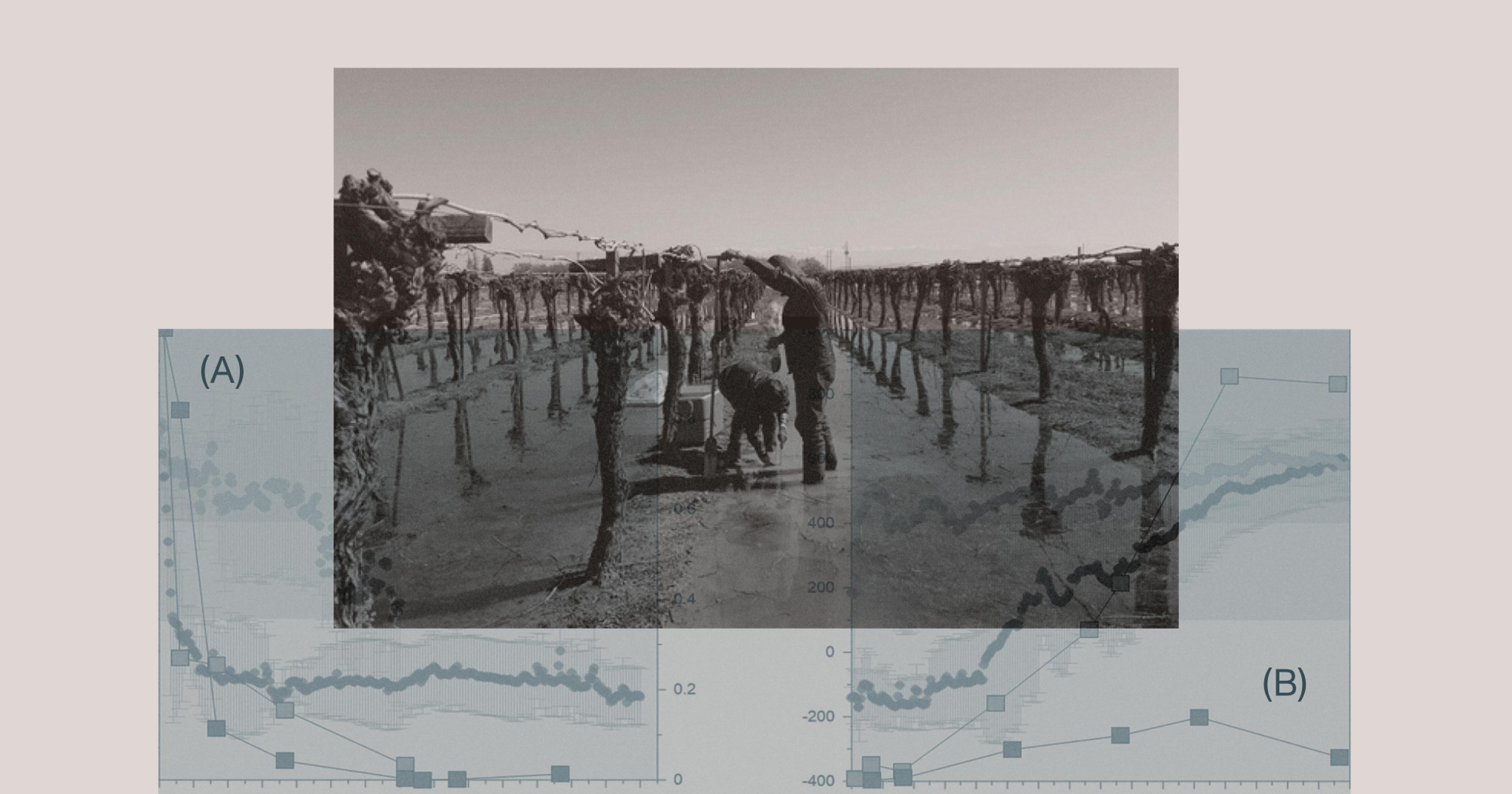

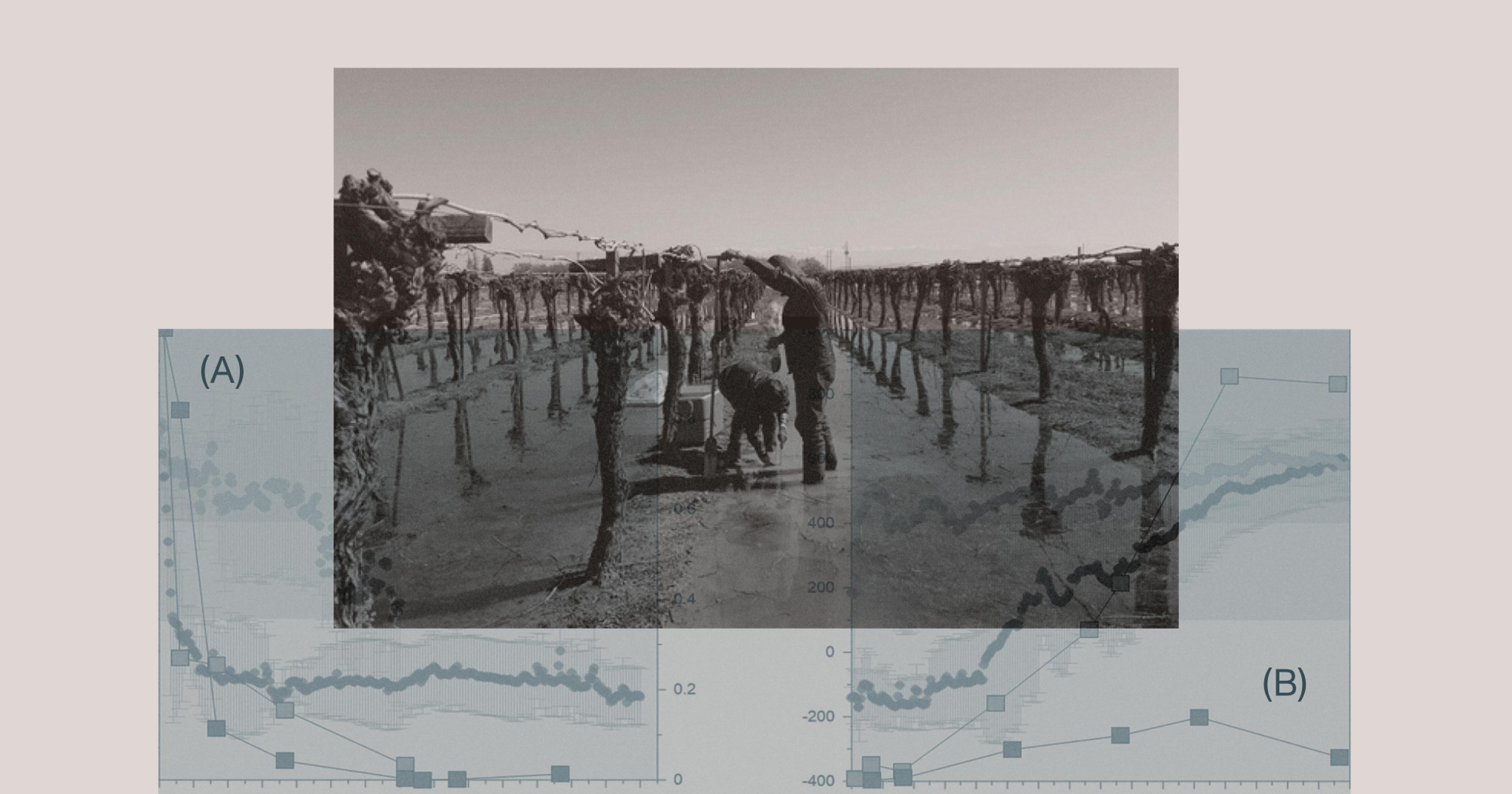

Farmland flooding could help with both extreme weather and depleted aquifers. But will it contaminate drinking water?

Farmland flooding could help with both extreme weather and depleted aquifers. But will it contaminate drinking water?

The expansive region, which is surrounded by rivers and lakes and includes vast croplands and forests, is often billed a climate haven due to its insulation from sea level rise, destructive hurricanes, and wildfires, not to mention its abundance of water.

Turns out that bounty of water — regularly pulled out of the ground to grow the dense fields of crops that blanket the region — may be why it’s stayed cooler than climatologists projected. Research has shown that large-scale irrigation has been mitigating the effects of climate change in many parts of the United States. But while this cooling effect sounds like a boon to a rapidly warming world, if farmers run out of water to irrigate crops, the effect could quickly be canceled, or even reversed.

“When you add water it cools the surface temperature, so it isn’t surprising at all that irrigation would cool the climate,” said David Lawrence, a scientist in the federally funded National Center for Atmospheric Research’s Climate and Global Dynamics Laboratory. Lawrence has published multiple studies on the topic. “In some parts of the world, cooling due to irrigation has been offsetting all of the warming you’ve been getting from greenhouse gas increases.”

In some regions, heavy irrigation has zeroed out and, in some areas, even reversed the effects of global warming on the hottest days of the year, benefiting approximately one billion people around the globe, according to one study led by researchers at ETH Zurich.

Nebraska is a prime example. The state boasts some of the few areas in the United States that have not experienced any warming in summertime temperatures over the last few decades. Researchers say that this is likely because it is the most vastly irrigated state in the country, tapping into its vast, thick reserves of the Ogallala Aquifer, a 174,000-square mile underground body of water that stretches from South Dakota to Texas.

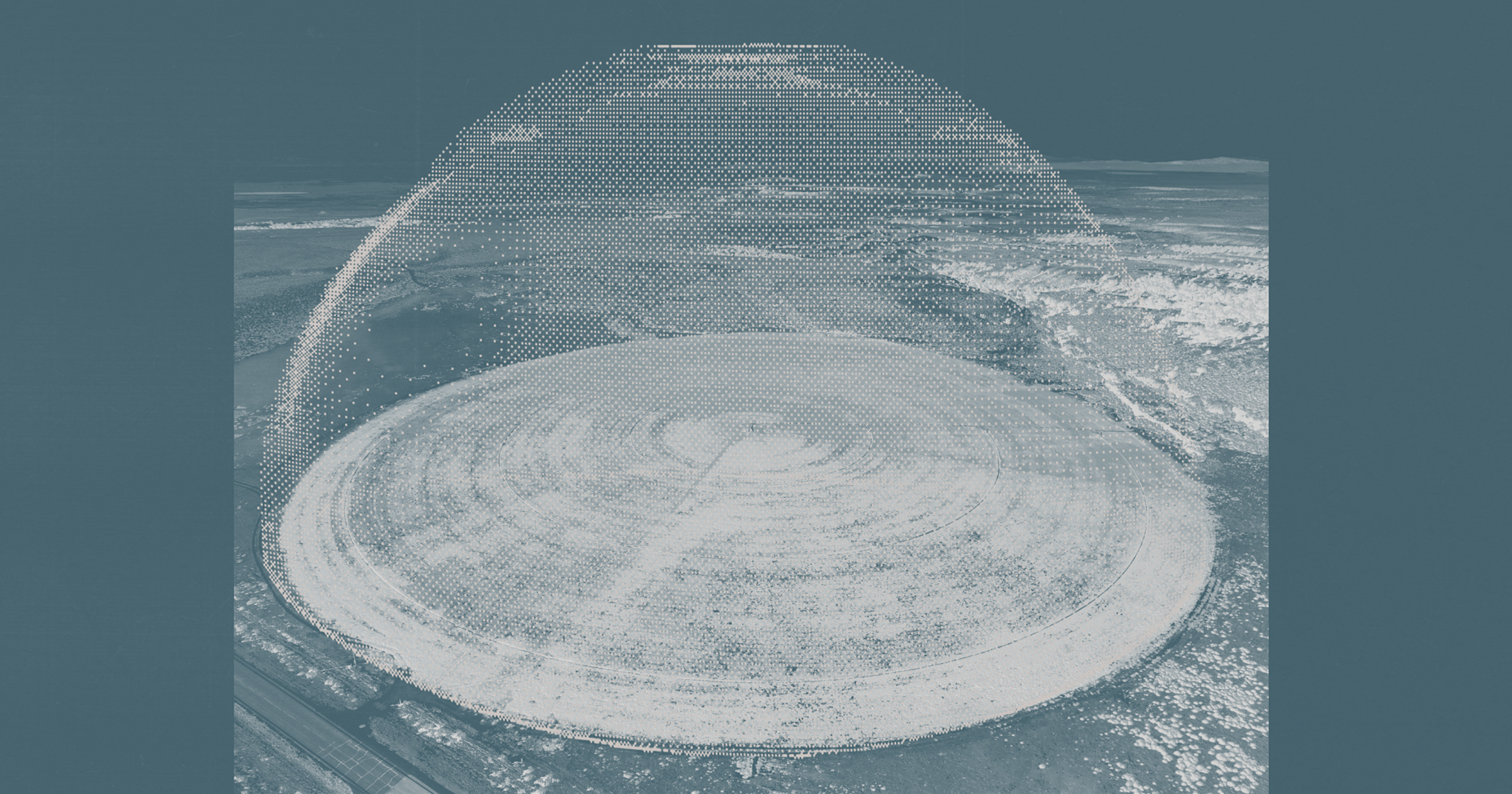

A working paper published in February examining the impacts of large-scale Ogallala irrigation found that regional center-pivot irrigation systems (the kind that create those round green circles seen from airplane windows) cool downwind temperatures up to as much as five degrees Fahrenheit during the month of August. The benefits are palpable for human lives and livelihoods. “Two of the most widely found effects [of water-moderated temperatures] are on human mortality and crop yields,” said Columbia University economist Wolfram Schlenker, one of authors of the study.

Schlenker and co-author Thomas Braun found that these cooler temperatures help plant growth overall and increase yields by avoiding those harmfully scorching days in downwind areas to the economic tune of $7 billion. Overall, this enhanced heat tolerance for the crops grown in the area — mostly corn and soybeans — equates to $26 billion in inflation-adjusted market value. This cooling effect could protect up to 9% of total corn production and 12% of total soybean production in certain areas during hotter years.

“In some parts of the world, cooling due to irrigation has been offsetting all of the warming you’ve been getting from greenhouse gas increases.”

Cattle grazing in areas downwind of these irrigation systems benefitted, too. Researchers found fewer illnesses and deaths as well as higher comfort in cattle during heat episodes.

But there’s another economic and social benefit, too. Their model found that human mortality costs related to irrigation-fueled cooler temperatures worked out to $240 million in overall savings in the immediate area as well as downwind counties. These mortality costs include hospitalizations from outdoor laborers who need treatment for heat exhaustion and other similar heat-related ailments, people who have suffered severe burns from touching blistering concrete and other surfaces, and serious complications from existing medical conditions. It is believed that heart attacks spurred by spiking temperature are responsible for about half of all heat-related deaths.

One of the major hitches in these findings, though, is throwing humidity into the equation, thus complicating the story for human and animal comfort.

Another study that looked at the impact of irrigation on humid heat extremes found that even when irrigation is cooling the local environment, that does not necessarily mean the conditions are safer for human inhabitants. In hotter regions, like the Mississippi Valley, irrigation can increase the number of days with dangerously high wet-bulb temperatures, which refers to the temperature at which a wet cloth can cool a thermometer. If the air is humid, it will take longer for the water from the cloth to evaporate and the thermometer will take longer to cool, similar to sweat on human skin.

If heat and humidity are too high, it becomes harder for the human body to cool down via sweating, the natural mechanism for removing heat from the skin and other organs. Irrigation also increases evapotranspiration — what many refer to as “corn sweat” — a combination of water evaporating from the surface of the ground and transpiring from plant leaves. This natural process, which has been exacerbated by climate change, means it can feel a whopping 15 degrees hotter in a cornfield than outside it.

This can be dangerous for farm laborers and, if it spreads beyond the field, it can impact local residents, too. “If you’re thinking about stress on the body in terms of heat and humidity, there tends to be more stress if it’s humid,” said Patricia Marie Parker, assistant research scientist for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). “How that will affect total stress going forward is an open question.”

Farmworkers and local residents in Nebraska may not feel the same cooling effects as locals in dry Arizona or California’s Central Valley.

So, while irrigation will most likely benefit crops and yields during hot spells no matter the region, the farmworkers and local residents in Nebraska may not feel the same cooling effects as locals in dry Arizona or California’s Central Valley.

The other major question is whether our water resources will last long enough to continue mitigating the increase in temperature long-term. All of these studies have looked at the impacts of inefficient irrigation methods, like center pivot systems, that pump huge amounts of water into relatively small areas. More efficient systems, like drip irrigation, do not boast the same heat-mitigating impacts.

And once irrigation has been reduced, all of that cooling gets reversed, warming can increase, and it can kickstart a new cycle of drought and aridification that exacerbates the warming effects of climate change.

In the Texas Panhandle, which has pumped out massive amounts of water from its portion of the Ogallala aquifer, the water table has been falling so much that farmers in the region have had to cut back on irrigation. While this year’s unusual rains helped the region to stay cooler longer, it’s still far from out of the woods this season. In spite of receiving 130% more rain than usual this year, the area surrounding Lubbock is experiencing the ninth-warmest period on record. Hopefully, all that rain will help replenish the local portion of aquifer to prevent even more water-use reductions that could make that warming even worse.

“As soon as you stop irrigation you get a warming effect that bounds us back,” said Schlenker. “There’s a beneficial effect while you do it, but it’s very hard to sustain.”