Concerns over soil health, reliability, and price have all played a part in slowing the electrification wave on U.S. farms.

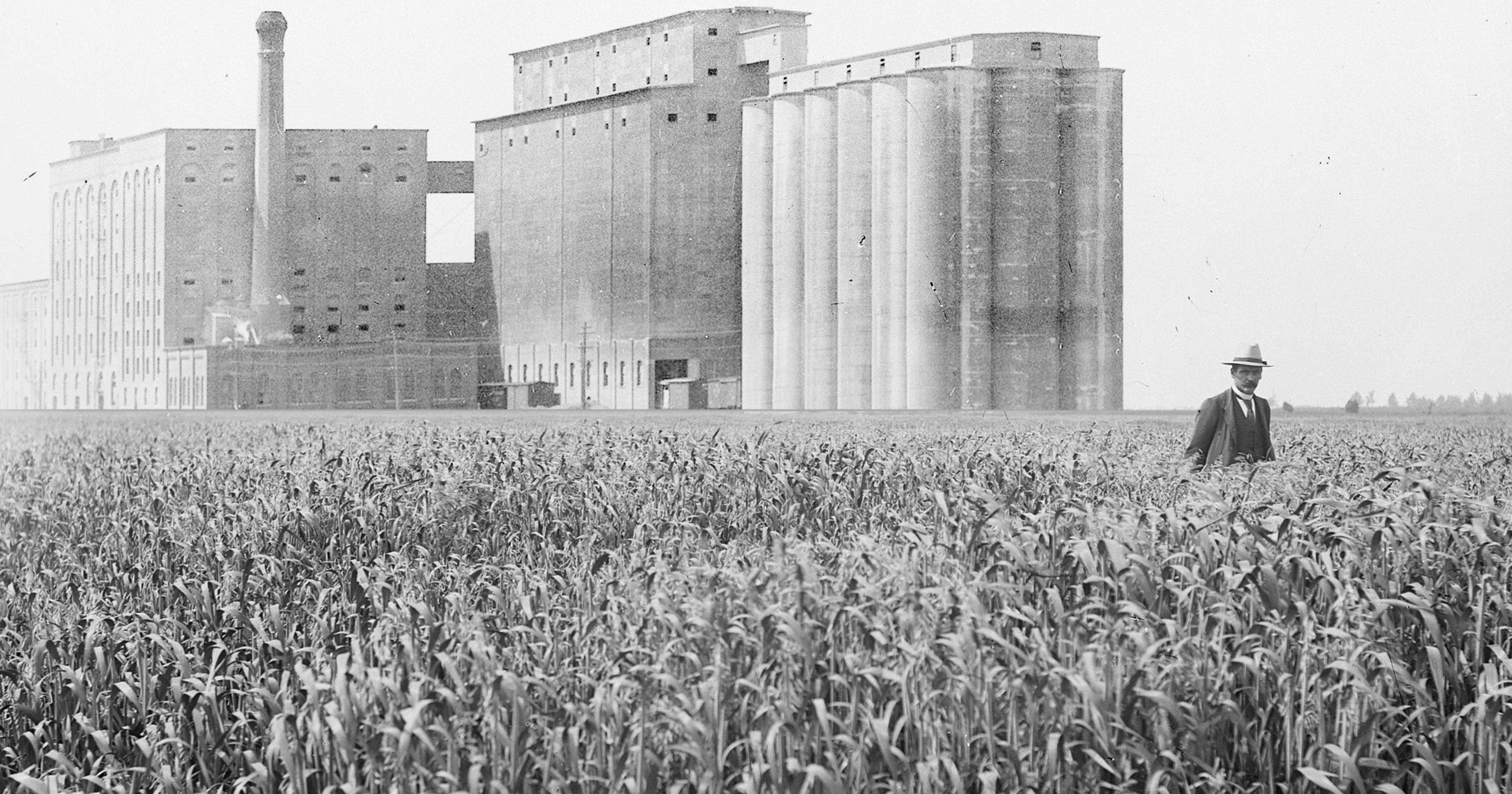

At the turn of the 20th century, petroleum started powering tractors, making workhorses, steam engines, and manual cultivators obsolete. Now, when green and yellow John Deere tractors plow fields and International Harvesters clog up county roads, they’re powered by fossil fuels.

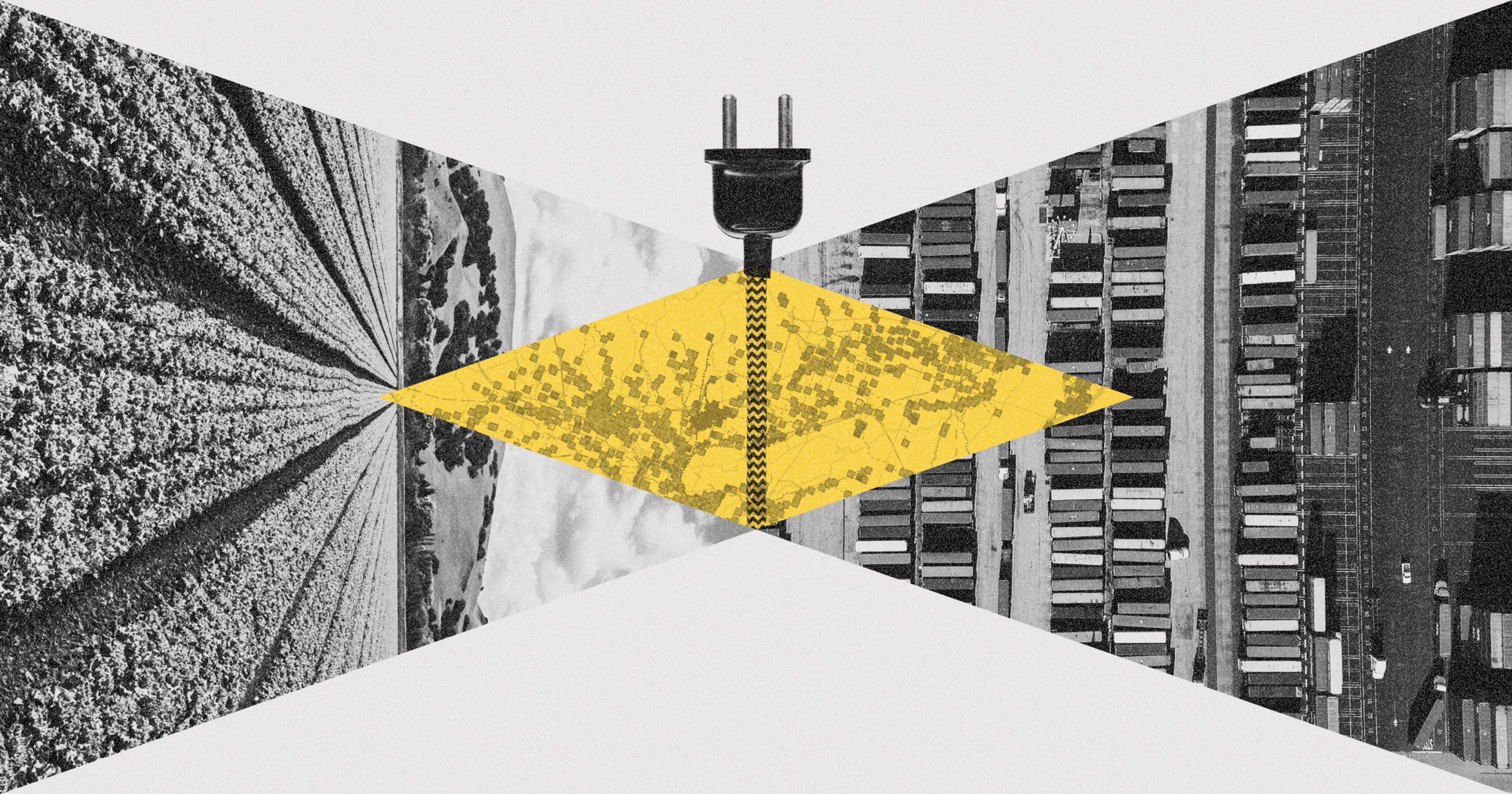

But as industries nationwide have set their sights on decarbonization, the fate of gas-powered tractors, invented in 1892, is fraught. The public and private transportation sectors have recently transitioned to electric vehicles. Shipping and logistic companies have slowly adapted to EVs, all pushing to reduce carbon emissions and air pollution. Personal vehicles and work machinery are also transitioning to electric power, just as petroleum replaced steam and horsepower over a century ago.

When it comes to farming, however, it is uncertain if the hum of an electric battery will soon replace chugging diesel engines. Farm equipment must walk a tightrope of being powerful and long-lasting, all while emphasizing minimal impact on the land.

As of now, electric tractors and other farming equipment are much harder to find on showroom floors. Deere isn’t projected to have a fully electric model until 2026. Other manufacturers like Massy Furgeson and Fendt are still developing electric tractors and are expected to hit the marketplace in the coming years.

New Holland, the agricultural machinery manufacturer owned by Case International Harvester, or Case IH, announced its first fully electric tractor a few weeks ago, the first of the large, familiar brands to bring this technology to market.

Electric farming equipment is among a group of industrial machines converting to electric batteries, from forestry to mining, that is projected to become a combined multi-billion dollar industry. That said, according to the clean energy nonprofit CALSTART, sales of electric tractors currently make up a mere fraction of yearly tractor sales.

The significant push for personal-use electric vehicles has grown as climate-conscious consumers take advantage of federal rebates for individuals to buy EVs, such as the Inflation Reduction Act’s $7,500 rebate program. But unlike with cars, there is no federal program to help ease the burden of producers wanting to purchase electric tractors and transition away from gas-powered machines. According to Steve Heckeroth, founder of Solectrac, an electric tractor manufacturer based in California, this lack of incentive is a roadblock for farms to decarbonize.

“It’s much more difficult for farming without incentives, and as a whole, agriculture is a much more conservative community,” Heckeroth said. “It’s a very hard sell in a lot of places.”

Outside of affordability, equipment size and weight are significant issues for electric tractors.

Solectrac specializes in electric tractors used on smaller farms or operations without intense planting and harvesting needs. Heckeroth said some of his company’s primary producers are organic farms, horse and hay farms, and a growing California vineyard customer base.

California is one of the only states to create a rebate program to ease the cost of purchasing electric tractors or other machinery for agriculture or commercial businesses. The state’s Clean Off-Road Equipment Voucher Incentive Project, or CORE, aims to replace farm equipment, freight trucks, landscaping equipment, port equipment, and even forklifts. Under the $40 million rebate program, certain electric tractors qualify for up to $30,000 in discounts.

Colorado offers a similar Clean Diesel Program, where businesses can replace diesel engines with lower or zero-emission machinery. As of last year, Oregon began testing a rebate program for electric and low-emissions farm equipment, but the program has yet to materialize.

Heckeroth said that this year’s massively important and ever-changing Farm Bill should mirror the California program. Solectrac was among the numerous organizations and businesses who marched in Washington D.C. earlier this year to urge federal lawmakers to make climate change and clean energy in agriculture a component of the legislation.

Outside of affordability, equipment size and weight are significant issues for electric tractors. Compact tractors like the ones Solectrac manufactures can use the added weight of the battery as an advantage when it comes to gaining traction. But when it comes to already-massive combines, harvesters, and tractors, adding electric batteries will increase the equipment’s weight and threaten soil health. Heavier equipment has been a trend for decades, said Rattan Lal, a soil scientist at Ohio State University.

According to his research, modern farming equipment can weigh as much as sauropod dinosaurs, the world’s largest land-walking creature (now extinct). In some cases, tractors can weigh up to 15 tons, which could harm the soil they are meant to cultivate.

“I don’t believe the battery technology is there for a big tractor. Even if it was, people would be nervous about the weight.“

New Holland’s recently announced T4 Electric Power tractor has an equivalent of 74 horsepower and was built with utility and small-scale tasks in mind. While the T4 has a battery life of roughly four to eight hours on one charge, the model is certainly heavier than its diesel-engine counterpart.

“Added weight in agriculture is not necessarily a bad thing. We get more traction with the tractor when it weighs more,” said Lena Bioni, New Holland product marketing manager.

That said, when soil is compacted, water and air are squeezed out of its pores, making it dense and dry. These conditions create a lack of air for plants and increase shallow roots. Lal noted that compacted soil also releases greenhouse gasses such as methane and nitrous oxide, contributing to climate change.

“Soil compaction with heavy machinery is a serious problem,” Lal said.

Lal is energy-agnostic regarding farming equipment — he is more concerned about the weight of a vehicle and how that weight is distributed. But, as seen with personal-use EVs, batteries are heavy and have significantly increased a car’s weight. He said that increased weight on soil is hard to reverse, too, and can have long-term effects.

“A heavy load, like a 20-ton grain cart on a single axle, can have an adverse impact on crop production and crop growth for five to seven years,” Lal said.

This reality is top of mind for major tractor manufacturers. In an interview earlier this year, John Deere’s chief technology officer Jahmy Hindman discussed the future of electric, lithium-ion-powered tractors, saying electrification was reserved for smaller, low-horsepower machinery.

Tractors are expected to last long days out in distant fields and currently, gas-powered machines can do just that.

“When I ran the numbers on it, if you power that with a lithium-ion battery today, it’s twice the volume, twice the weight, twice the mass, and four times the cost. That just doesn’t pencil,” Hindman told AgWeb.

This assessment was based on John Deere’s 8R tractor model, which, according to the company’s website, has a base weight of 25,800 pounds. Hindman’s estimation would place an electric 8R tractor at nearly 26 tons. (Representatives for John Deere did not respond to an interview request.)

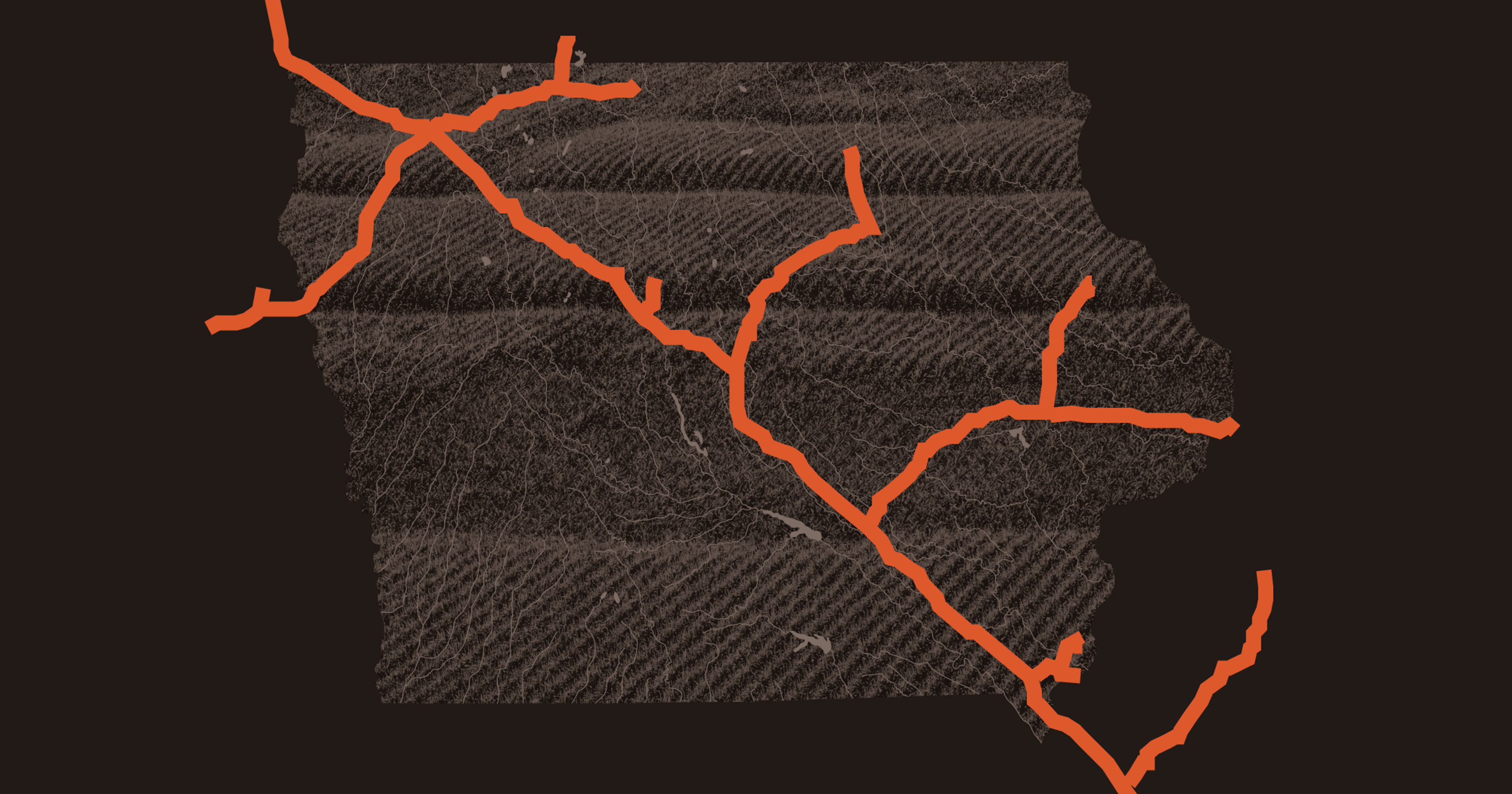

Heavyweight tractors are crucial for farmers like Bryce Hediger. He operates a 4,000-acre millet and grain farm in Colorado. A fourth-generation operation, the land has previously seen various types of gas-powered equipment; electric-powered machines and tools have now become commonplace at the farm.

“We’ve bought into the electric thing pretty hard,” Hediger said.

Hediger said work trucks and vehicles used on the farm are electric, the storage buildings and warehouses have electric pallet jacks and forklifts, and numerous farm and yard tools on the operation are battery-powered.

But gas still reigns supreme at the Colorado grain farm when it comes to heavy-duty jobs.

“I don’t believe the battery technology is there for a big tractor,” Hediger said. “Even if it was, people would be nervous about the weight. We don’t want to be hauling huge amounts of weight out in our field and creating compaction.”

He said electric tractors currently suffer from a lack of long-term battery life and increased weight, endangering soil health. Hediger currently limits the fuel he has to use and opts for energy efficiency when it comes to gas-powered equipment.

Reliability is critical when it comes to heavy machinery. Tractors are expected to last long days out in distant fields and currently, gas-powered machines can do just that. Bringing extra fuel along is commonplace if a tractor runs out miles away from the operation or a gas station. Currently, some Solectrac models can last 3 to 8 hours, depending on the use, off a full battery charge. Another electric tractor manufacturer, Monarch Tractors, claims to support 14 hours off a fully charged battery. But, going back and forth between charging stations and fields is less appealing when farmers are dealing with long working days.

According to New Holland, the T4 is not intended for traveling long distances. “The fact that the utility tractor, in most cases, returns to the farm every night or maybe doesn’t leave the farm at all means they’re the perfect size for electricity. They’re always going to be close to a power source where they can easily recharge,” Bioni said. Orders for the T4 will be opened up in coming weeks.

While clean energy is slow growing for every facet of a farm, Hediger currently operates a wind turbine and solar panels. It’s a small operation, but he said the power is enough for his electric vehicles if the primary power grid becomes unreliable.

“I would lean more towards making my own power, just to be more reliable on my own resources and having more control over the things I need rather than relying on power companies or government intervention,” Hediger said.