Last year, the DOJ exposed a price- and wage-fixing conspiracy by some of the largest U.S. poultry producers that they said “harmed a generation.” Will the government follow through on holding them accountable?

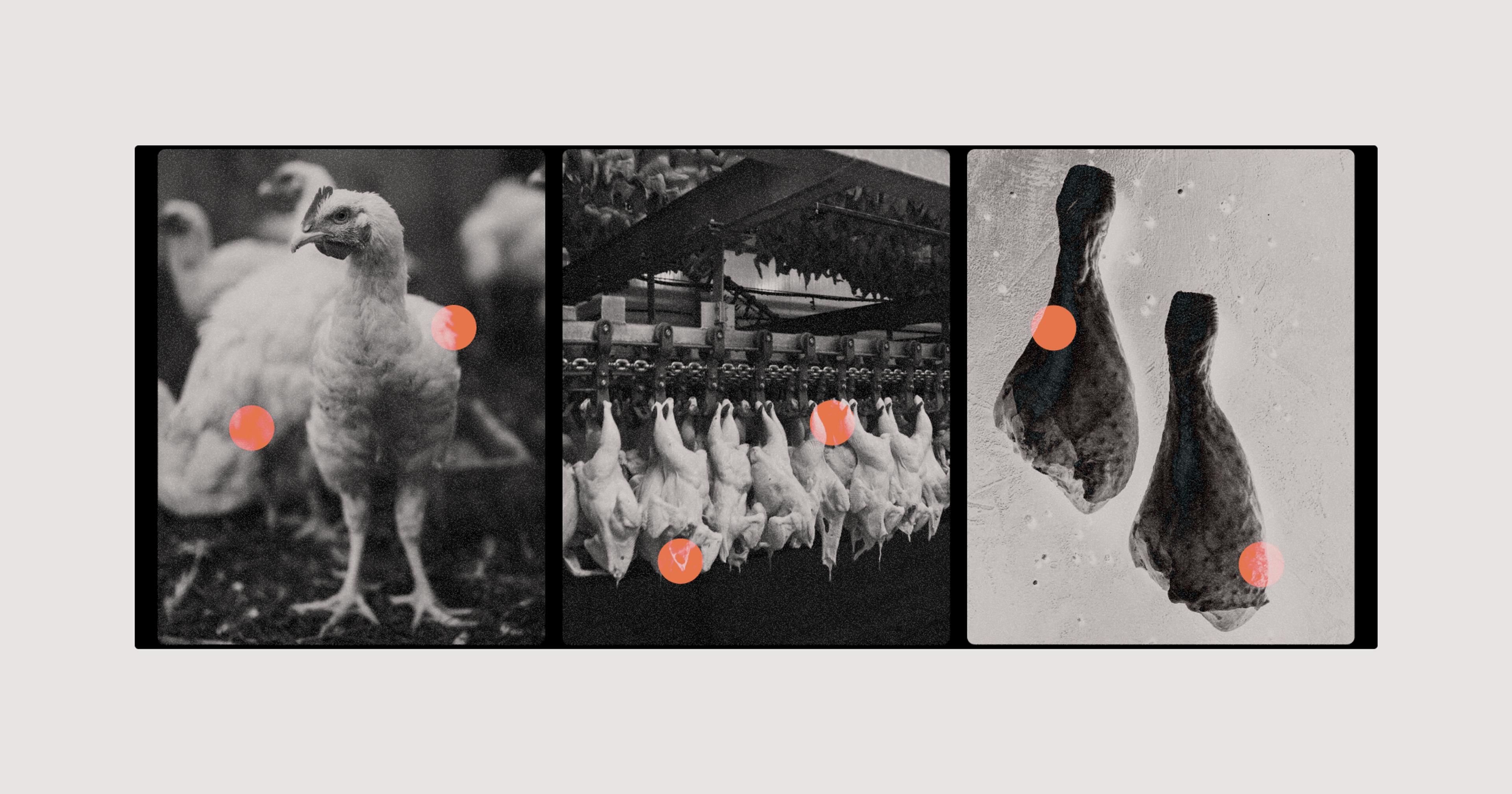

Contract farming within the poultry industry is a now-common practice for its biggest companies. As first envisioned decades ago, it was effectively outsourcing labor — large processors provide fertile eggs to a sprawling network of small farmers, who then send back grown chickens for processing and sale.

For some farmers, though, the steady work can also be deeply restrictive and open them up to predatory practices. And since the 1990s, the evolution of this system has led advocacy groups like Farm Action to argue that companies are able to “legally and discreetly put out of business” farmers that speak out against abusive practices.

Georgia farmer Etta Lee watched her father, P.M. Lee, come to regret the contract work. She says he didn’t like all that power consolidated in one client, leaving him powerless to set prices or push back against unreasonable demands.

“They were the only ones that could buy your chickens,” Lee recalled. “That made him mad.”

Lee’s family found the contract system for poultry farmers to be predatory enough that they stopped participating years ago. Etta Lee, who now runs Annie’s Farm in Dupont, Georgia, still sells eggs and poultry — but directly to consumers, and on her own terms. Her position foreshadowed a larger reckoning that would come to the industry years later: the revelation that major companies abused these contracts to create a “tournament system” jockeying poultry growers against each other, and a set of price- and wage-fixing cases that kept farmers from negotiating higher rates for decades.

The issue is severe enough that the USDA proposed a rule change in 2022 that would require corporations to share expected earnings and better pay transparency for farmers. That proposal is still winding its way through bureaucratic channels. Meanwhile, federal prosecutors have unearthed a series of conspiracies and collusion within the poultry industry in an attempt to derail what they call “anticompetitive” behavior that left chicken prices high and worker payments low.

On the flip side, antitrust regulators have allowed massive companies to merge and increase their market share. As a result, according to legal experts, antitrust advocates, and economists, these contradictory realities raise more questions than answers about where the poultry industry is headed.

Biden on Offense

Emails were just the beginning, but provided the biggest paper trail. According to a Department of Justice (DOJ) mid-2022 complaint, there were shared datasets, secret meetings, private investigators, and more, all proving that major poultry processing companies had spent 20 years knowingly breaking the law to pay their employees and suppliers as little as possible.

The conspiracies documented by the DOJ laid out a complex system meant to share information between competitors, so that contract growers and workers couldn’t negotiate for higher wages. This played out for decades, according to the DOJ’s findings, dating from “2000 or earlier.” On top of clandestine meetings and communications, the scheme even involved hiring outside companies to compile information about worker salaries that could be shared to companies that were supposedly in competition.

Defendants Cargill (the largest privately held corporation in the U.S.), along with Mississippi-based Sanderson Farms and Georgia-based Wayne Farms (both multi-billion dollar poultry companies), all settled out of court last year, agreeing to pay $85 million. They entered into a consent decree with the DOJ that barred them from communicating about salary and supplier prices with competitors. It also ordered them to adopt and follow the USDA’s proposed rule change for poultry growers, as well as increase their pay for full-time employees.

“There’s been a tremendous amount of consolidation ... and a tremendous amount of abuse.”

These cases were neither isolated within the industry nor the largest examples of financial wrongdoing. In 2022, Tyson Foods, Pilgrim’s Pride, Perdue Farms, and 19 other companies paid $35 million to settle a price-fixing suit against them in Washington state. And in 2020, poultry processor Pilgrim’s Pride pled guilty to price fixing charges brought by the DOJ, agreeing to pay nearly more than $110 million in fines.

The Biden administration has made a clear priority of targeting the poultry industry. In several lawsuits in the past couple years, DOJ lawyers have outlined an industry that has harmed its workers and customers with impunity, mainly through tools like collusion among big major players.

“No surprise at all that the food and agriculture markets were high on the list,” said Diana Moss, president of the nonprofit American Antitrust Institute. “There’s been a tremendous amount of consolidation in those markets that make up the supply chain and a tremendous amount of abuse.”

When they published the consent decree with Cargill, Sanderson, and Wayne, the DOJ also pointed out that they have a campaign dedicated to investigating aspects of the poultry industry, implying that more lawsuits may be coming. While those haven’t materialized yet, questions remain about the department’s strategy for reining in the poultry industry’s “anticompetitive” behavior.

Anticompetitive Culture

“It’s that time of year already,” a Wayne executive wrote to eight of the company’s competitors, according to court records, including executives at Sanderson and Cargill. It was 2010 and budget season for the companies. The employee then requested the other companies’ “projected salary budget increase recommendation.”

The conversation from there got hyper-specific. Beyond just basic salary info, the companies began to request how wages might change in different situations.

In 2015, an executive from an unnamed company emailed the group to ask, “what your starting rate is for these kids hired right out of college?” In 2016, the conversation shifted to overtime. “That reminded me that I had a question for the group also,” wrote the director of compensation at an unnamed co-conspirator. “We are trying to determine what is reasonable for salaried employee [sic] to be compensated for working 6 and/or 7 days in a work week when the plant is running … Do you pay extra for these extra days worked for salaried (exempt) employees? If so, how is that calculated?”

Altogether, there were 18 other companies that participated in these exchanges alongside Sanderson, Wayne, and Cargill.

The DOJ described in their 2022 complaint a culture of poultry companies that set up email chains, gatherings and one-on-one meetings of poultry executives, spreadsheet wage tracking, and more. It depicts an elaborate scheme that would normalize prices across the industry and effectively take money out of the pockets of laborers. The DOJ alleges that these companies built a tournament system, where underperforming suppliers would be “penalized” by getting less income, even though the companies themselves could boost those results through their “inputs … such as chicks and feed.”

“This conspiracy suppressed competition in the nationwide and local labor markets for poultry processing,” the DOJ wrote in a court filing. “Their agreement distorted the competitive process, disrupted the competitive mechanism for setting wages and benefits, and harmed a generation of poultry processing plant workers by unfairly suppressing their compensation.”

Ninety percent of chickens grown and sold within the U.S. are produced under the contract system.

Meanwhile, consumption of poultry products has dramatically increased in recent decades. Market research firm IBISWorld published data showing that as of 2023, there are 113 pounds of poultry available for each person within the U.S., a nearly 20-pound increase from 2013. And USDA data shows that in the past decade, poultry outgrew beef and pork to become the largest meat industry in the country.

The increased market share of major companies like Cargill has given them massive control of this sector. According to the National Chicken Council, there were 9.2 billion chickens produced in 2022. The organization also found that 90 percent of chickens grown and sold within the U.S. are produced under the contract system, meaning they come from a small handful of huge processing companies like Cargill and Tyson Foods.

The National Chicken Council refers to “vertical integration” as a major boost for the industry. The concept involves businesses acquiring ownership of several parts of their supply chain in order to make it more streamlined and profitable — a system the government has sought to restrict. Yet the chicken council has published reports saying the model of corporations owning every step of the growth, processing, and distribution process is the future of all agriculture.

Industry trade publication Watt Poultry found in 2019 that consolidation within the top 10 poultry producers continued to centralize market power among an increasingly small group. Between 2005 and 2015, for example, the number of chicken processing companies shrank from 840 to 706. The same report found that small processing companies collapsed from 9% of the market to 4%.

A Contradictory Environment

The strategy of aggressively targeting poultry companies is a break in recent norms for the poultry industry. Before the Biden administration began looking into lawsuits, the main voices raising concerns were nonprofit advocacy organizations like Farm Action. This is enough of a shift that proponents of big-business agriculture have taken note.

“Efforts from the Biden administration to roll back the previous administration’s regulatory easing has us all concerned for our futures,” wrote Lucius Adkins, the president of the United Poultry Growers Association in a 2021 newsletter, praising the Trump administration’s prior rollback of regulations.

At the same time as the regulatory crackdown, however, the Biden administration has taken a light hand in actually breaking up massive industry players and blocking acquisitions that allow them to control more of the market.

The exact same week that the DOJ announced its settlement with Cargill, Wayne, and Sanderson, the defendants were given a green light by the agency to move forward with a $4.5 billion acquisition. Cargill, in a joint venture with Continental Grain, combined Sanderson and Wayne Farms into a new privately held business. According to Washington Monthly, this allowed them to grow their market share of the poultry industry from 46% to 51%.

In the eyes of antitrust advocates, this means companies like Cargill are still free to operate with impunity.

One Missouri-based agriculture nonprofit responded to the news by calling it a “bad deal” for farmers in a newspaper editorial. “Why conspire with your competitors when you can just merge?” wrote communications director for the Missouri Rural Crisis Center Tim Gibbons.

In the eyes of antitrust advocates, this means companies like Cargill are still free to operate with impunity.

“They now have a consent decree, requirements about not sharing information, but the companies that were in that case now have even more of an incentive to share information because they’ve now gotten even larger,” Moss said. “When you allow a merger between two firms that concentrates the market … they will have even more power now to violate the terms of the consent decree.”

Economist Jason Winfree, professor at the University of Idaho, said consumer prices are lower due to the economies of scale afforded by huge agribusiness concerns. Although he expressed reluctance to break up these firms, he acknowledged the potential for abuse inherent to single companies controlling large sections of a market.

“Where there are examples of big firms using their market power to increase prices, then the DOJ should consider using antitrust laws to keep prices low,” Winfree said.

More Questions Than Answers

In other sectors, Biden’s antitrust approach has had more notable wins, including an effort to block JetBlue’s takeover of Spirit Airlines and Microsoft’s attempt to buy Activision Blizzard. But, because of this success, the former “czar for competition policy” Tim Wu has warned antitrust advocates that they shouldn’t celebrate prematurely, suggesting that there could be “blowback” from corporations.

Moss sees a darker shift due to the DOJ’s decision to allow Cargill’s acquisition of Wayne and Sanderson farms. She isn’t sure why the DOJ would have made this choice, but her first guess was that they had limited resources and must have felt the consent decree was more important. The DOJ did not respond to an interview request for this story.

“This was a really uncomfortable set of outcomes,” she said. “Kudos to them for bringing that case, but what the heck is going on in this merger? … It really undercut the enforcement that they took in the wage-fixing case.”

Meanwhile, New York University law professor and antitrust expert Eleanor Fox maintains confidence in Biden’s DOJ: “The Biden administration really stands for more aggressive antitrust.” She assumes investigators must have had confidence that the increased market share Cargill, Sanderson, and Wayne would get as a result of their merger wouldn’t be harmful. “I don’t think they would have allowed it if they thought it was going to hurt competition,” Fox said.

For Moss, it is too early to tell how effective the DOJ’s strategy has been, and what the impact will be for poultry consumers and workers.

“They are trying new things and they are seemingly committed to an enforcement program, but I don’t think we’re at a stage yet where we can evaluate,” Moss said. “We don’t have enough data points yet.”

Meanwhile, farmers like Lee are seeing the benefits of a more independent approach, giving them freedom to adapt and maintain side projects. Free of the contract system, she was able to make changes to her farm during the pandemic and produce a much wider range of food. She said she’s even been able to sell her local, free-range poultry at a lower cost than supermarket chickens.

“I don’t have the overhead, I have a niche market,” Lee said, pointing out that she wasn’t used to seeing herself as competition for big poultry companies. “I guess if there’s enough people like me they might want to put us out of business.”