A handful of agroecology projects across the island aim to produce food locally and sustainably, shoring up against costly imports and climate calamities.

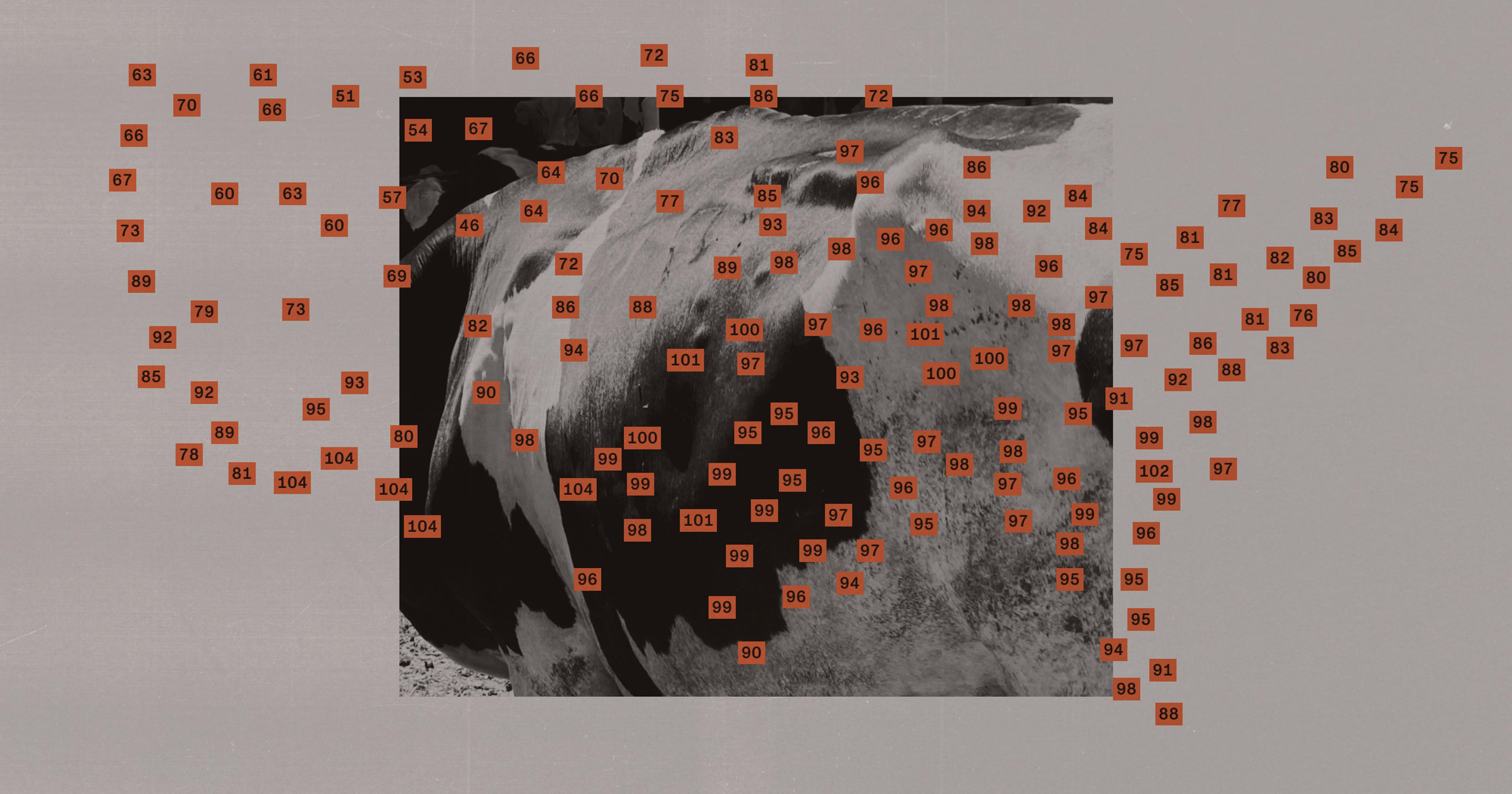

The first thing visitors see when they arrive at Finca La Zafra, an agroecological project in Gurabo, Puerto Rico, is the welcoming restaurant. Bartenders shake up cocktails to an upbeat soundtrack while servers weave through the space, balancing abundant plates. The scene is compelling enough, but the Finca’s most innovative offering is hiding in plain sight: Eco-Agricultores 100x100, its recently launched program that equips budding farmers with machinery, tools, seeds, compost, technical guidance, and, most importantly, a 100x100 plot of land to grow anything they can dream up, on the Finca premises.

Ask any Puerto Rican in the food or hospitality industry, and they’ll share an inconvenient truth: The island imports more than 80% of its food, and that includes produce. This reality has created significant challenges in the recent past; when Hurricane Maria disrupted the supply chain in 2017, the media got to review the anachronistic Jones Act, which complicates imports from the U.S and steeply affects the cost of goods. Every port strike or shift in policymaking is also a bitter reminder of how dependent the island is on the U.S. mainland.

But recently, educational projects, experimental farms, innovative restaurants, and hands-on programs like Eco-Agricultores 100x100 have been carving out a different narrative. Led by a young generation of farmers and entrepreneurs, these initiatives shine a spotlight on local, sustainable produce Puerto Ricans are excited to both grow and consume.

“We need farmers in PR. We need to grow our food and depend less on importation,” said Jan Diaz, president of Finca La Zafra. “It’s important for our communities to have access to fresh and healthy food and it’s important for individuals to figure out where to get this food.”

According to professor Angela M. Linares Ramírez from the Agro-Environmental Sciences Department at the University of Puerto Rico, local agriculture in PR faces a range of environmental, financial, and labor-related challenges. There are environmental hardships like soil degradation that’s driven by erosion, nutrient depletion, and salinization, and water scarcity caused by erratic rainfall patterns, prolonged droughts, and inefficient water management practices. Then, there’s the cost of inputs, and the scarcity of young farmers.

“Food imports, mainly from the Americas, are another challenge and competition for local farmers,” Linares Ramírez said. Then there’s the cost attached to agriculture — everything from fertilizers, pesticides, equipment, and electricity. Not to mention actual land ownership. “These costs place a heavy burden on local farmers, especially since many depend on imports for these inputs, driving up their prices,” she said.

At Finca la Zafra, Eco-Agricultores 100x100 tries to tackle some of these obstacles. At first, the Diaz family, who purchased the 30-acre parcel in 2019, didn’t see it as a major opportunity. Coming into the project with a background in hospitality — the family owns several restaurants on the island — “We just wanted a space to decompress from the fast-paced life and to harvest a few crops for our restaurants on a small scale,” Diaz said.

A nudge in the right direction, however, came from a course at El Josco Bravo, an agroecology project and training school that had been pioneering the discipline in Puerto Rico since 2004. “We started to understand the importance of agriculture here in PR and the impact it has in our daily life,” Diaz said. “We also knew how hard it was to find local products for our restaurants, let alone for an individual, and decided it was our responsibility to join the movement of Puerto Rican farmers.”

The family decided to launch an application process for several 100X100 plots in August, inviting people with or without experience to experiment and plant. As of now, six farmers are running agricultural projects at the Finca. “We are excited to see them thrive as we continue to understand how else we could help them grow,” Diaz said.

While the scope may sound small, Eco-Agricultores 100x100, as well as other projects scattered through the island, have a big task at hand — shifting the cultural mindset among the younger generation of Puerto Ricans to position farming as a respectable, promising, and viable career.

In addition to Finca la Zafra and Josco Bravo’s offerings, Carite 0.3 in Guayaba, Frutos del Guacabo in Manatí, and Finca Neo Jibario in Rio Grande operate similar models: working farms combined with agrotourism, featuring a restaurant or dinner series, educational tours or workshops, and, at times, lodging.

“We need farmers in PR. We need to grow our food and depend less on importation.”

These new initiatives tend to avoid pesticides and adopt permaculture and hydroponic practices. At Finca Neo Jibario, insects are kept at bay with the help of “teas” brewed from tobacco plants, and compost is used to enrich the soil. What started as a patio passion project in San Juan is now a 10-acre operation, growing kale, passionfruit, acerola, lettuce, eggplants, and more, depending on the season. “The land was used for sugarcane over 50 years ago, and it wasn’t impacted too much by chemicals and pesticides, which was perfect for us,” said Antonio Castro Barreto, general manager at Finca Neo Jibario .

A few years ago, Barreto pivoted from a career in personal training to join his brother, founder Francisco Castro, in his quest to revive local agriculture. He never looked back. “People are starting to care more about local, nutritious produce,” he said. Having “direct experiences with the farm,” according to Baretto, is also important. “With the tours, especially for children, and the private dinners, we try to establish that connection,” he said. “So people really see and feel the importance of local agriculture in Puerto Rico.”

While the learning curve can be steep — according to Linares Ramírez’s students are still hesitant to adopt farming as a career, and establishment commercial farms are equally apprehensive to tap into innovative, environmentally friendly methods — things are slowly changing.

“There are pockets of farmers interested in innovation, particularly those who see long-term sustainability and profitability potential through modern farming techniques,” said Linares Ramírez, who, three years ago, introduced a new course on sustainable agricultural management. Additionally, she said, there’s been “a growing interest in agroecology and regenerative farming practices, which focus on sustainability, biodiversity, and soil health.”

This shift, Linares Ramírez added, reflects broader global trends toward environmental consciousness. “Puerto Rico, with its fragile ecosystems, is especially well-suited for these practices,” she said.

The appetite for local produce is also growing on the consumer side. Finca Neo Jibario has been working with PRoduce, an island app offering subscription boxes and connecting shoppers with local growers and farmers; launched in 2020, the app received James Beard recognition a year later. On the app’s produce section, each product is labeled “local” or “imported,” with the former outweighing the latter.

More and more restaurants are also pledging allegiance to locally grown produce by sourcing it from local farms or growing it themselves. Aldeana, a farm-to-table restaurant and event space opened in 2024, is a good example of Puerto Rico’s new culinary wave — restaurants that promote farm-to-table and locality.

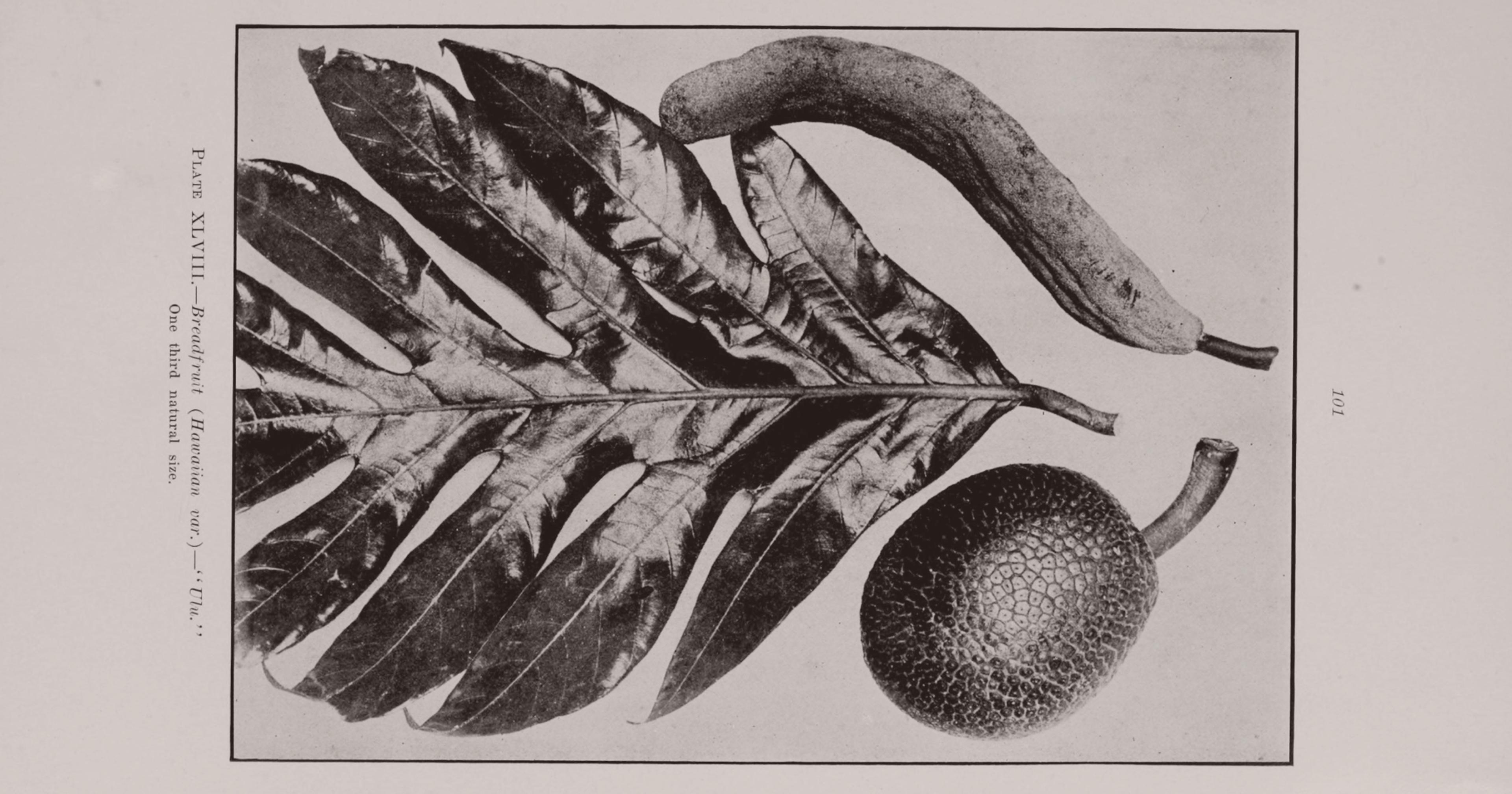

In addition to sourcing everything locally, the chefs also grow seasonal produce on site, from herbs like cilantro and recao — a popular Puerto Rican green used in stews and sauces, to avocados, guava, breadfruit, and edible flowers. “The more we can support local agriculture, the better,” said Aldeana chef and co-owner Raúl Correa. “It’s a fundamental part of both our business and personal philosophy.”

Correa views the restaurant as a part of a movement, emphasizing that sourcing locally is what sets these emerging restaurants apart. “A tomato is a tomato, but what makes the difference is the soil and climate,” he said. “When we travel, we want to taste the tomatoes from that region, and when you visit us, we want you to experience ours.”