Cloud seeding is a decades-old method of forcing clouds to release their precipitation. It’s an effective technique, but it’s falling on the weight of conspiracy theories.

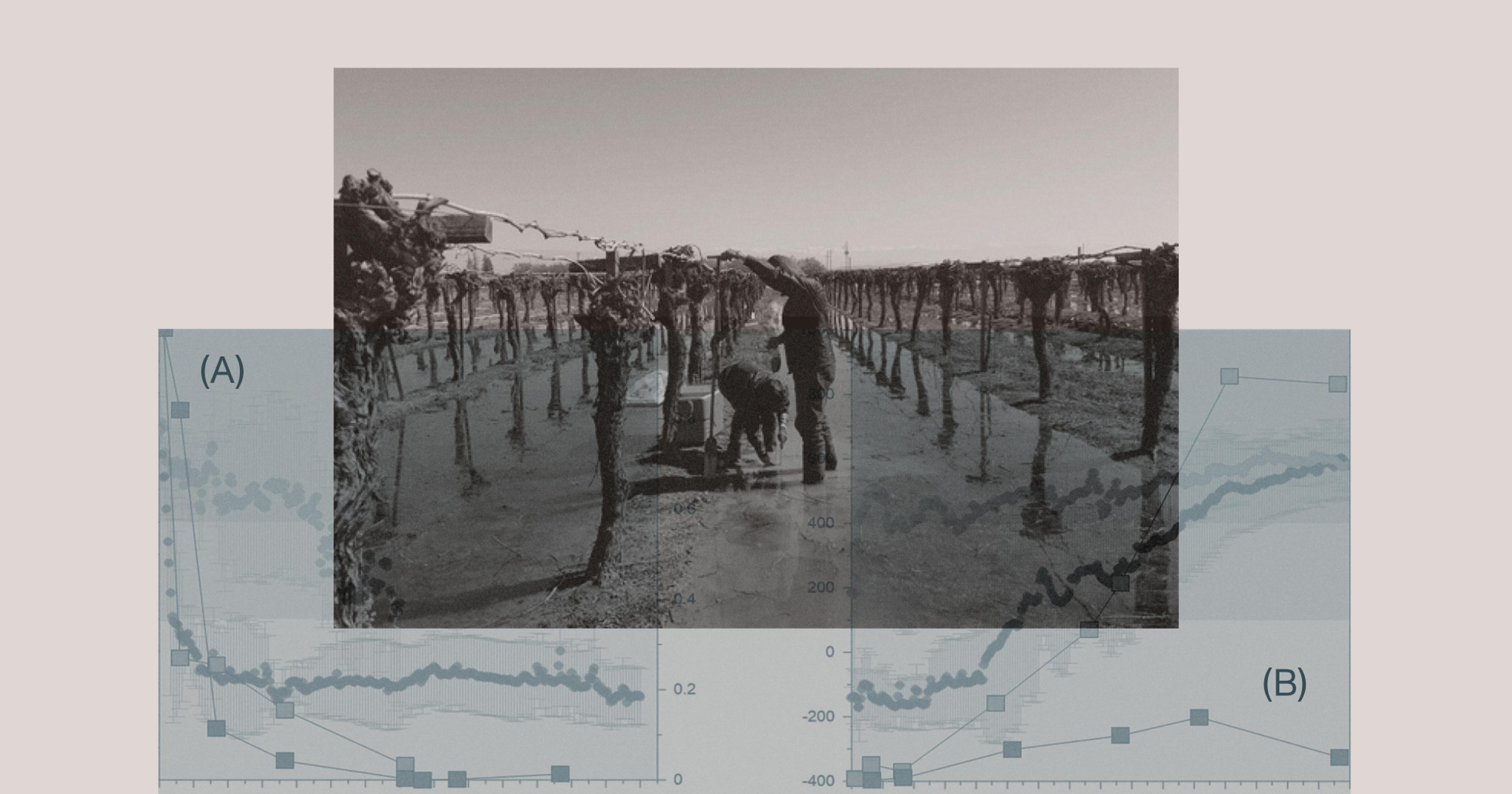

Western North Dakota is a land of extremes. Farmers there spend their summers either anxiously waiting for rain or dreading the approach of a hailstorm, which can send golf-ball sized chunks of ice shooting towards their crops at up to 100 miles per hour. But they’re not completely at the mercy of the weather, thanks to a technique called cloud seeding, which encourages the precipitation to fall as rain instead of hail. For three months each summer, planes shoot small amounts of the chemicals silver iodide and dry ice (frozen carbon dioxide) into the clouds and then monitor the effects on the farmland below.

The idea of humans controlling the weather sounds like the stuff of science fiction, but the practice of weather modification is very real, and has been going on for decades. In recent years, though, a backlash has developed against long-running cloud seeding efforts in North Dakota, driven by environmental concerns as well as misinformation and conspiracy theories proliferating on the internet and social media.

Last year, two North Dakota counties voted to end their cloud seeding operations, limiting the program to just two remaining counties and part of a third. And a bill to criminalize the practice entirely came up in the state legislature, though it was defeated in February.

This opposition to cloud seeding could make life more difficult for the farmers it’s supposed to help, said Darin Langerud, director of the Atmospheric Resource Division of the North Dakota Department of Water Resources, which runs the cloud-seeding program.

“We’re facing misinformation — not only on this topic but other topics relating to science and technology,” Langerud said. “It’s a difficult thing to combat. The ability to get proper information in people’s hands is a challenge.”

Cloud seeding was invented in 1946 by a scientist working for General Electric. Seeking to test it out on a larger scale, the federal Bureau of Reclamation — an agency tasked with increasing water availability for agriculture in the arid West, —turned to North Dakota. It started the world’s longest-running aerial cloud seeding program — one that continues to this day, now administered by the state.

Texas and New Mexico have similar summer hail-suppression and rain enhancement programs, while California, Utah, Nevada, Colorado, Wyoming, and Idaho all run winter cloud-seeding programs — it increases snowpack, which helps fill reservoirs and keep hydroelectric dams running. Fifty countries around the world, including the United Arab Emirates, China, and India, are known to experiment with cloud seeding.

Scientists tend to disagree about the impact of this technology, though research from more than 50 years of cloud seeding in North Dakota suggests that it’s effective at meeting limited goals.

“People believe this is nefarious activity. Cloud seeding is somehow getting wrapped up in these discussions where it doesn’t belong.”

Cloud seeding works by harnessing the properties of atmospheric physics, said David Delene, a University of North Dakota professor and editor of the Journal of Weather Modification. Clouds are filled with tiny drops of water, which won’t condense and fall as rain until they have something to latch onto — what are known as ice nuclei. Chemicals like silver iodide can serve as artificial ice nuclei, Delene said, in cases where the clouds won’t release moisture on their own. The process can’t create rainfall out of thin air, but instead gives already-existing clouds a little push.

Cloud seeding can create longer-lasting storms that drop their water over a larger area, but it’s also not 100% effective; not every cloud that’s seeded ends up releasing rain. It’s also hard to track results because researchers have to compare post-seeding precipitation totals with the amount that would have fallen without the intervention — something that’s difficult to estimate. Its effects on hail suppression are even trickier to track, because it’s hard to say for sure that hail would have fallen if a cloud wasn’t seeded, or that the hailstorm would have been more intense.

The data that does exist, though, suggests that investing in cloud seeding tends to be better than doing nothing. A 2022 study looked at 30 years of data in the counties that participated in weather modification programs, and found that cloud seeding had increased precipitation between 5 and 15 percent. That may not mean much for some farmers, as precipitation in North Dakota can vary wildly from one year to the next, making a 10 percent increase fairly minimal in some years, Delene said. But it can make a huge difference during times of drought, and especially in avoiding damage from hailstorms. Other studies have found that the state’s program reduces hail damage by 45 percent while also increasing crop yields.

The program costs the state less than $1 million annually and can rake in economic returns of 40 or 50 times that, Langerud said — making it a fairly low-risk, high-reward endeavor.

Despite these effects, the cloud seeding program has become the target of suspicion in recent years. In January, a bill that would have banned “weather engineering, cloud seeding, stratospheric aerosol injection, or other atmospheric activity that is harmful to a human or the environment” was introduced in the North Dakota House of Representatives.

Known as HB 1514, it was driven by fears about the “chemtrail conspiracy,” Langerud said, referring to the theory that the government is secretly spraying toxic chemicals in the air to sterilize people or, yes, control the weather — a funhouse mirror distortion of what’s actually happening. The theory has been bolstered by people as powerful as President Donald Trump’s Health and Human Services secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

A bill was introduced that would have banned “weather engineering, cloud seeding, stratospheric aerosol injection, or other atmospheric activity that is harmful to a human or the environment.”

“People believe this is nefarious activity,” Langerud said. “Cloud seeding is somehow getting wrapped up in these discussions where it doesn’t belong.”

The opposition is also driven by a lack of understanding, Delene said. Some people question whether more rainfall in one area can cause droughts in a nearby county, which Delene said isn’t how storms work; there’s plenty of water in the atmosphere to go around, even with cloud seeding. Many also fear the effects of silver iodide, which Delene explained is used in such small amounts as to be nearly undetectable, and isn’t considered a health or environmental concern.

Still, to try to answer some of these questions, officials like Langerud travel to the counties that still allow cloud seeding operations. They host public meetings and answer questions before flights begin in the summer. He pointed to the trove of information on the department’s activities, including records of each flight, available on its website to emphasize its dedication to transparency. But although HB 1514 was eventually defeated in the state legislature, Langerud thinks that the conspiracy theories that fueled its rise are likely to stick around, putting the future of cloud seeding in doubt. “My sense is, this issue is probably not going to go away anytime soon,” Langerud said.

Even if no statewide bill succeeds in killing the program, farmers who believe in its benefits fear that this kind of piecemeal downsizing will cause it to be cancelled eventually — a sort of death by a thousand cuts. That includes George Siverson, a now-retired livestock farmer who lives in rural Bowman County in the southwest corner of the state.

At 83, Siverson knows what it’s like to experience the full fury of a hailstorm, like the one that busted the windows of his car and killed several of his sheep six years ago. He believes cloud seeding has helped reduce hail damage, although not everyone agrees — Siverson often overhears gripes about the program in the local bar and restaurant.

“You hear those comments around the table, especially if there’s adverse weather,“ he said. “That it’s dry because they seeded clouds, or that they didn’t get up there in time.”

But although the question of ending the program has come up on the ballot in Bowman County several times in recent years, voters there have so far decided to keep it. Siverson estimated that about 60 percent of the farmers he talks to support cloud seeding.

“I don’t think the benefit is as much as it used to be,” Siverson said, “but I would hate to see it cancelled.”