A D.C. insider argues BIPOC farmers may never see benefits from the Justice40 Initiative, a sweeping historical program for disadvantaged communities.

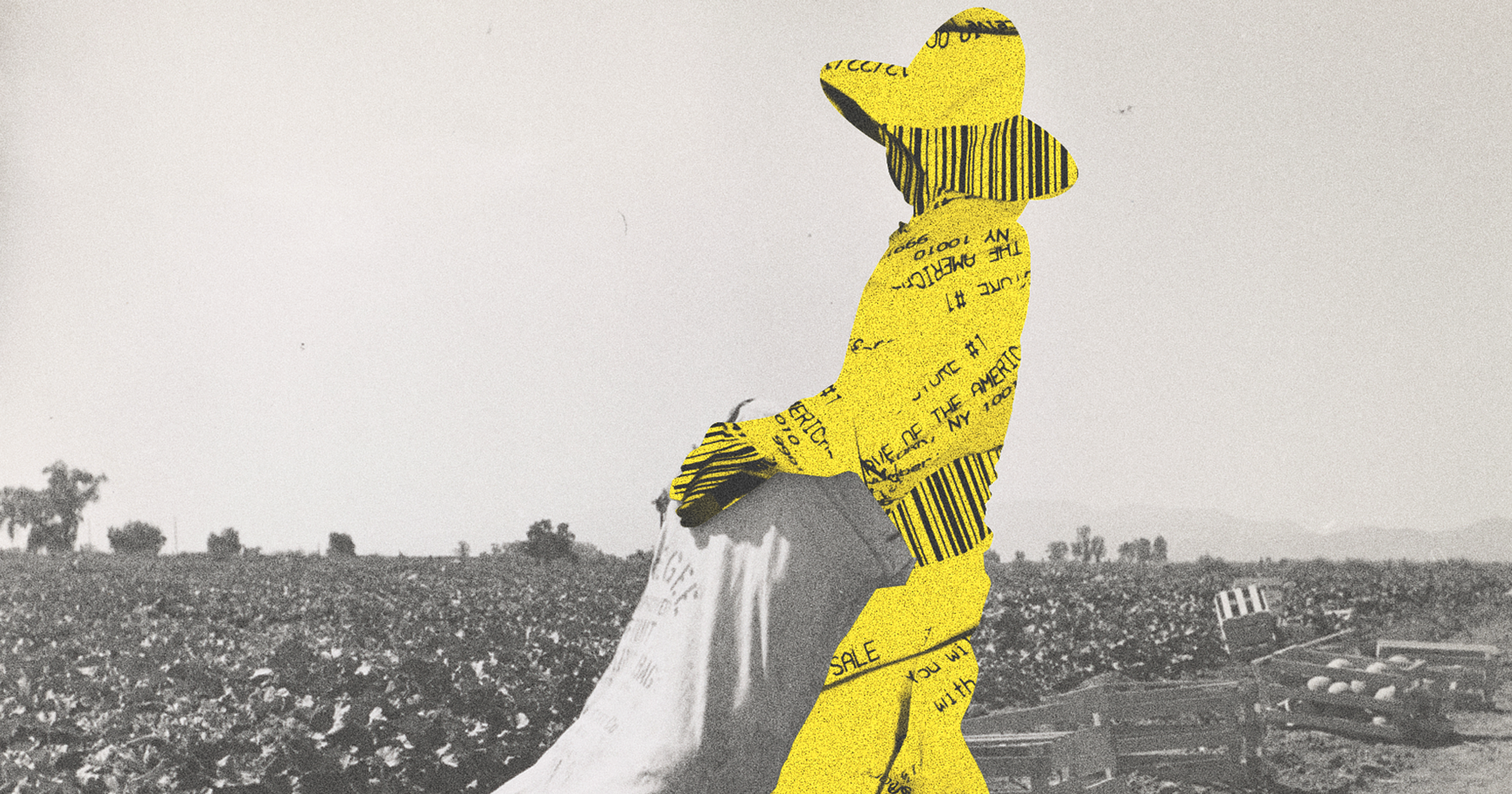

USDA has a long and well-documented history of racial discrimination, more explicit than most federal agencies. In recent years, the agency has responded with decisive steps to acknowledge and address some of the resulting harm. To wit: A few days before Democrats made history by nominating a woman of color to run for the presidency, the Biden-Harris Administration announced execution of more than $2 billion in payments to farmers and ranchers who had experienced harm from USDA discrimination.

These payments are beneficial and important, if only a start. USDA Secretary Tom Vilsack said of them, “While this financial assistance is not compensation for anyone’s loss or pain endured, it is an acknowledgement.” John Boyd, president of the National Black Farmers Association, put a finer point on it to AP News: “It’s like putting a bandage on somebody that needs open-heart surgery.”

Of course, even those funds were fiercely contested; the USDA payments were first blocked by court order in June 2021, responding to complaints they did not provide equal protection under the law to white farmers. The assistance may never have gone through if Congress hadn’t broadened the scope beyond Black beneficiaries.

That decision may be of lasting consequence to how loan programs operate moving forward, as NPR’s Ximena Bustillo noted during an All Things Considered segment on the payments. “Since these new programs are race neutral, Black farmers and other farmers of color say that the move could hide the scope of the unequal lending practices,” Bustillo said.

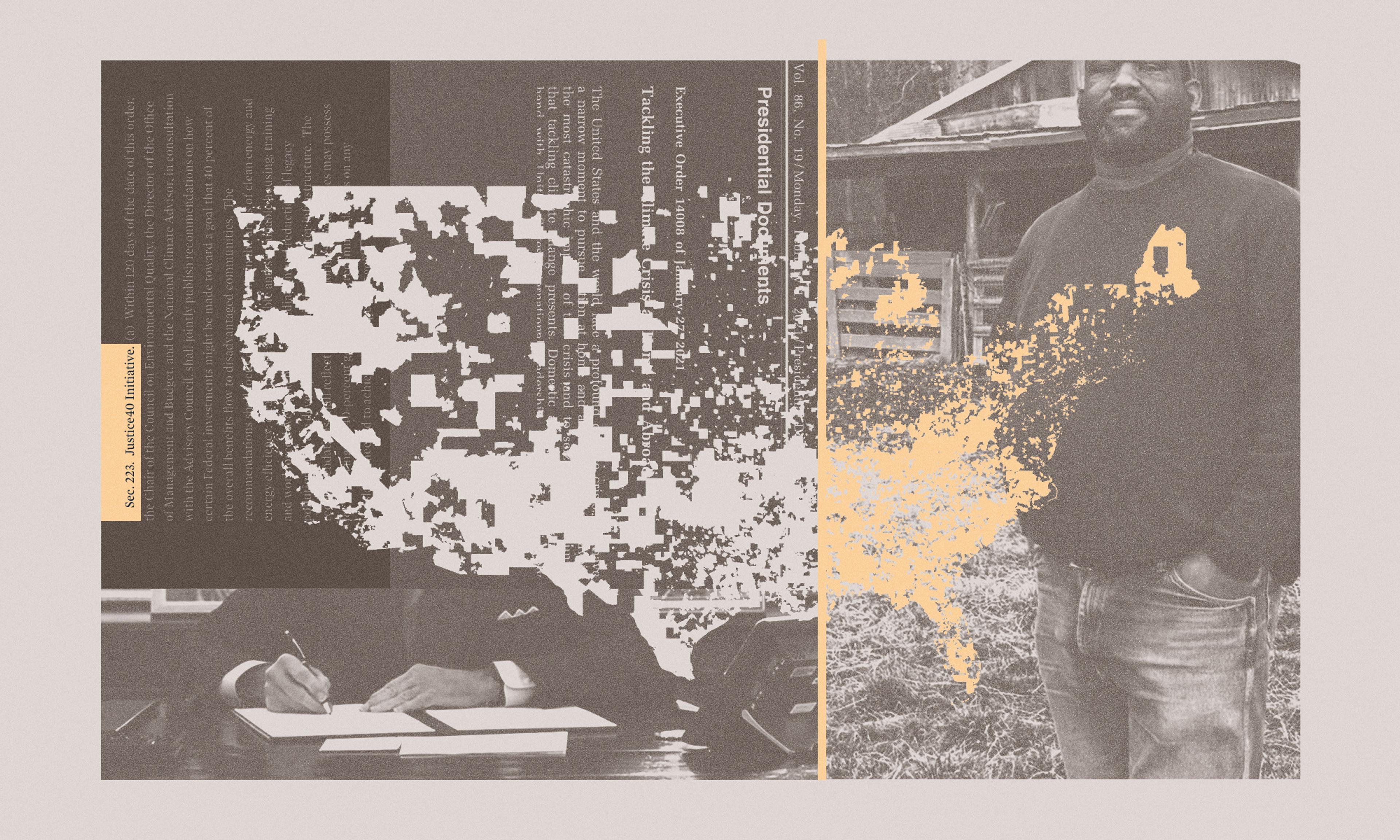

While these payments were executed in consideration of past actions, USDA has also been afforded significant authority to invest in a more equitable future through the Justice40 Initiative. The Biden administration implemented the initiative in tandem with significantly heightened federal investments toward climate-friendly programs. In essence, Justice40 calls for the realization of at least 40% of the benefits of these investments to occur in communities disproportionately impacted by social and political marginalization and pollution.

Mechanically, this “whole-of-government initiative” applies to “any grant or procurement spending, financing, staffing costs, or direct spending or benefits to individuals for a covered program in a Justice40 category.” Agencies have declared their lists of impacted programs; USDA’s can be viewed here. But while communities of color — rural or urban — are disproportionately impacted by underinvestment and pollution, many BIPOC farmers may not recognize themselves as the intended beneficiaries of the program.

Justice40 does not explicitly acknowledge itself as a vehicle of racial justice, which protects the effort from interference but may ultimately undermine its potential to make USDA programs more accessible to communities of color. A report on Justice40 implementation issued by Resources for the Future stated “The White House acknowledges that it left race out of the [eligibility screening] because of concerns that legal challenges might result if federal funding is directed to communities based on race.”

The Justice40 Initiative uses the term “disadvantaged communities” to designate its beneficiaries, an effort to avoid legal entanglements like those leveled on USDA’s discrimination payments. However, if agencies implementing Justice40 could speak more freely about the racial factors of environmental justice, they could draw more BIPOC farmers and organizers toward USDA programs.

“The White House acknowledges that it left race out of the [eligibility screening] because of concerns that legal challenges might result if federal funding is directed to communities based on race.”

Justice40 defines underserved communities by either geography or the experience of “common conditions” beyond geography; White House guidance uses “migrant workers” as an example. In January 2024, impacted agencies were given the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool to identify communities to which Justice40 benefits should flow.

Having worked as a consultant to farmers and grassroots nonprofits through the pandemic and recovery, I can attest to the difficulty of alerting folks to the existence of federal support programs like Justice40. These are people who have historically been held at arm’s length by USDA; they would surely prove more likely to endure the daunting application processes if they understand the government was attempting a new way to direct support to their communities, specifically. But in my experience, BIPOC farmers are more likely to understand themselves and their communities in terms of race and culture, rather than as “socially disadvantaged” or “marginalized” communities.

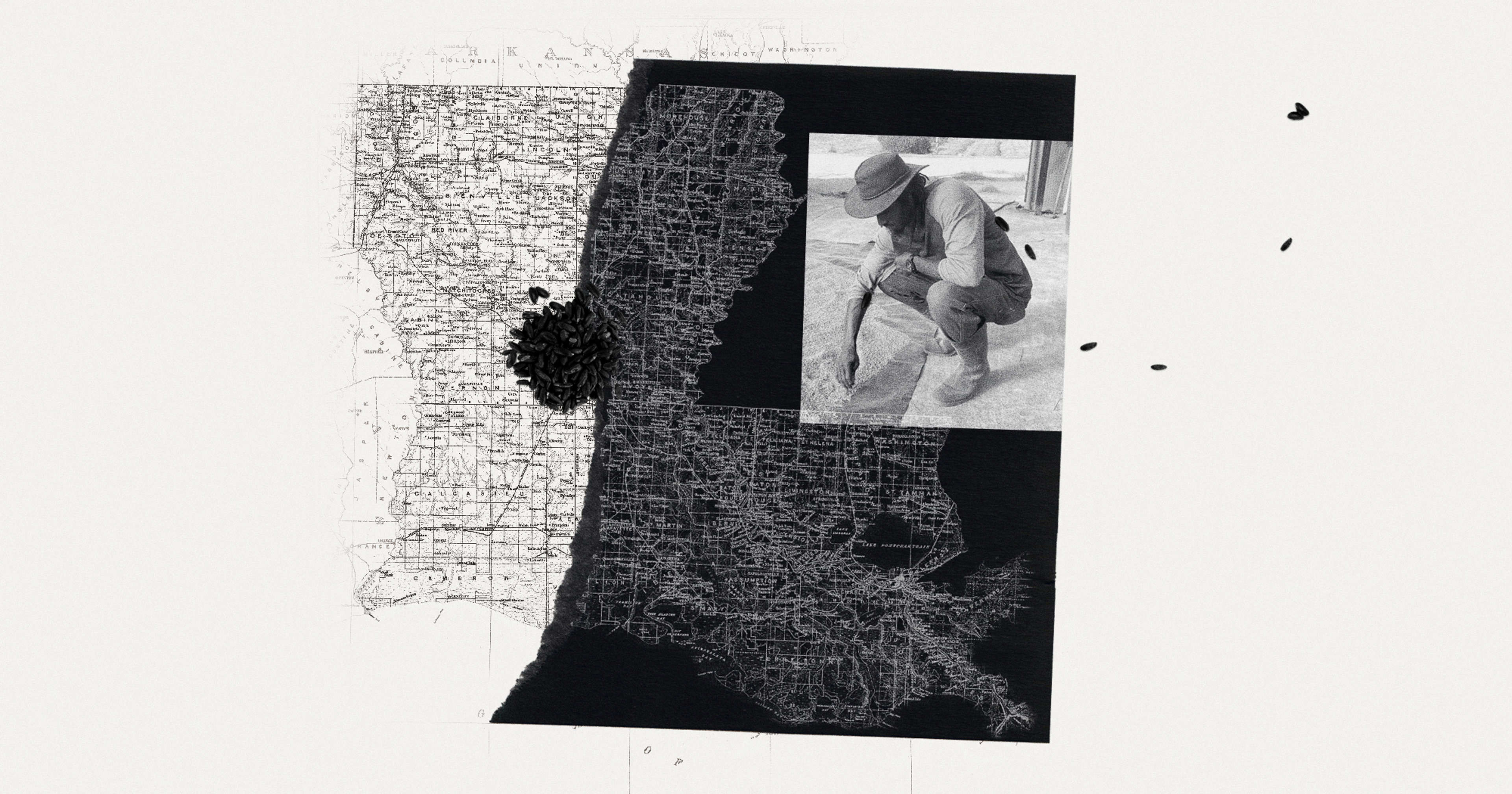

Tiffany Bellfield El-Amin is a third-generation farmer in Madison County, Kentucky, and executive director of Kentucky Black Farmers Association. Her family’s history is in tobacco production — she saw that resources from major settlements with cigarette manufacturers tended to almost exclusively benefit white farmers in her state. El-Amin asserts that government programs have been made specifically unavailable to BIPOC farmers since the Civil Rights era.

When asked whether President Biden’s Justice40 initiative will support farmers like her, El-Amin said, “People have to show up to demonstrate that there are actually Black farmers in Kentucky.” As USDA agencies continue implementation of the Justice40 Initiative, they may continue working with their familiar farmers and clients, rather than using Justice40 as an opportunity to reach out to new constituencies. There are far too few BIPOC farmers in the U.S. for USDA to fulfill its Justice40 obligations by working with them exclusively. But the agencies may miss opportunities to empower BIPOC farmers in producing the benefits for Justice40 communities.

There are about 600 farms owned by Black farmers in Kentucky, or less than two percent of the total farms in the state (the national average is under one percent). But USDA’s implementation does not have to directly benefit BIPOC farmers. Agencies like the Farm Service Agency (FSA) and Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) can choose to work with white farmers to produce benefits in underserved communities in order to satisfy Justice40 requirements.

“People have to show up to demonstrate that there are actually Black farmers in Kentucky.”

Consider a hypothetical where USDA agencies acknowledge water quality impairment in a Justice40 community. USDA will seek to fulfill part of its Justice40 obligation by improving water in the community. In many cases, this could be accomplished by supporting upstream farmers who use sustainable practices, regardless of whether that farmer can be considered a member of the Justice40 community.

El-Amin, in asserting the need for BIPOC farmers in Kentucky and elsewhere to make their presence known, noted that agency outreach cannot afford to discount race and culture in their outreach efforts. “The farmers I work with do not think of themselves as underserved or socially disadvantaged.” Without acknowledging the specific challenges BIPOC farmers continue to encounter, many will not realize the federal government is making extra effort to partner with them.

It’s a politically savvy strategy — the Justice40 Initiative is more likely to survive by making it race-neutral. But where a genuine focus on racial justice could mean foundational change to the USDA and signal a new course to other vested stakeholders, Justice40’s focus on “underserved communities” may allow business to proceed as usual.

That said, El-Amin expresses cautious optimism, viewing Justice40 as an opening for farmers and organizers like her to take a seat at negotiation tables that had previously been beyond reach. “It would not take away from the majority to make sure that everyone is represented,” she said.