The latest wave of avian influenza brought COVID-style modifications to the 2024 Pennsylvania Farm Show.

The eggs may have perished. The day that they were transported to Tim McGowan’s wood-paneled basement in Myerstown, Pennsylvania, a storm tore across the state that shattered trees and turned fields into brown lakes and burst the banks of the Susquehanna River. Power lines are no match for 50 mile-an-hour winds, and the electricity went out overnight. When McGowan came down to the basement in the morning, he found that the incubator that was housing 90 eggs had gone cold. There was nothing to do but wait and see if they’d hatch.

The story of a possible mass egg mortality event in a civilian basement technically starts in South Carolina in January 2022. That’s when an American wigeon died of H5N1, the current strain of avian influenza that’s threatening flocks all across the nation. Or alternatively, the origin of this story can be found in China in the fall of 2021, when that strain was first discovered. You could even trace it back to 1878, when avian influenza — then deemed “fowl plague” — was first identified as the culprit for the deaths of several Italian flocks.

But for the sake of simplicity, let’s stick to recent history. Once it was discovered in South Carolina, it took three months for H5N1 to make its way to Lancaster County in southeastern Pennsylvania, which has the highest concentration of poultry farms in the state. Between April 2022 and July 2023, 4.6 million chickens in 67 flocks died from avian flu there.

The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture’s logical response was quarantine, a term that most post-2020 Americans regard with a sort of PTSD-afflicted weariness. Flocks could not come in contact with each other; sanitation procedures had to be observed before entering facilities with eggs or live chickens; waste had to be sequestered and carefully disposed; and, of course, poultry shows were verboten.

In early December, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture confirmed that the 2024 Pennsylvania Farm Show in Harrisburg would, for the second year in a row, feature no live poultry and eggs. Judging of the poultry competition would be limited to printed photos, pinned rather tragically to a wall of empty cages.

The chick-hatching exhibit, where fairgoers can watch live chicks emerge from their eggs, is beloved. That could be simply because chicks are very cute, and human instinct makes us fond of baby animals. Or it could be because it adds a poetic cycle-of-life element to an agricultural fair, where it is difficult to ignore that the majority of the animals that are being petted and admired and prized are destined for slaughter. Perhaps the antidote to that revelation is to showcase the start of life: a dandelion-soft baby chick, fighting its way to join the world.

And yet even if they escape a power outage or an avian pandemic, the chicks born at the Farm Show will be distributed to farming families and largely raised for meat. Animal husbandry requires reckoning with raising an animal from birth — even loving it — before killing it to feed yourself or your customers. And to get the true philosophical experience of farming at the Farm Show, you ought to be able to see the chick be born within walking distance of the stand where you buy three chicken tenders for $6.

Organizers of the 2024 Pennsylvania Farm Show deemed that the opportunity to witness the miracle of birth would not be sacrificed to the current wave of highly pathogenic avian influenza. It would have to go remote.

Eve Andrews

Dana Lape is something of a poultry consigliere in the Lebanon Valley. He’s president of the Lebanon Valley Poultry Fanciers, Lebanon County’s 4H Poultry Club leader, and serves on the board of several local farm shows. Lape coordinated the first remote egg-hatching in the region for the Lebanon Area Fair in 2015, due to an outbreak of avian flu that the U.S. Department of Agriculture deemed the country’s “largest animal health emergency.”

The local paper, the Lebanon Daily News, offered to host an incubator and run a livestream from its office, broadcasting slow cracks and emerging beaks on the paper’s website and social media pages. (“It was funny because that was the last year they were at that building,” said Lape. “It sort of closed out the Lebanon Daily News building.”)

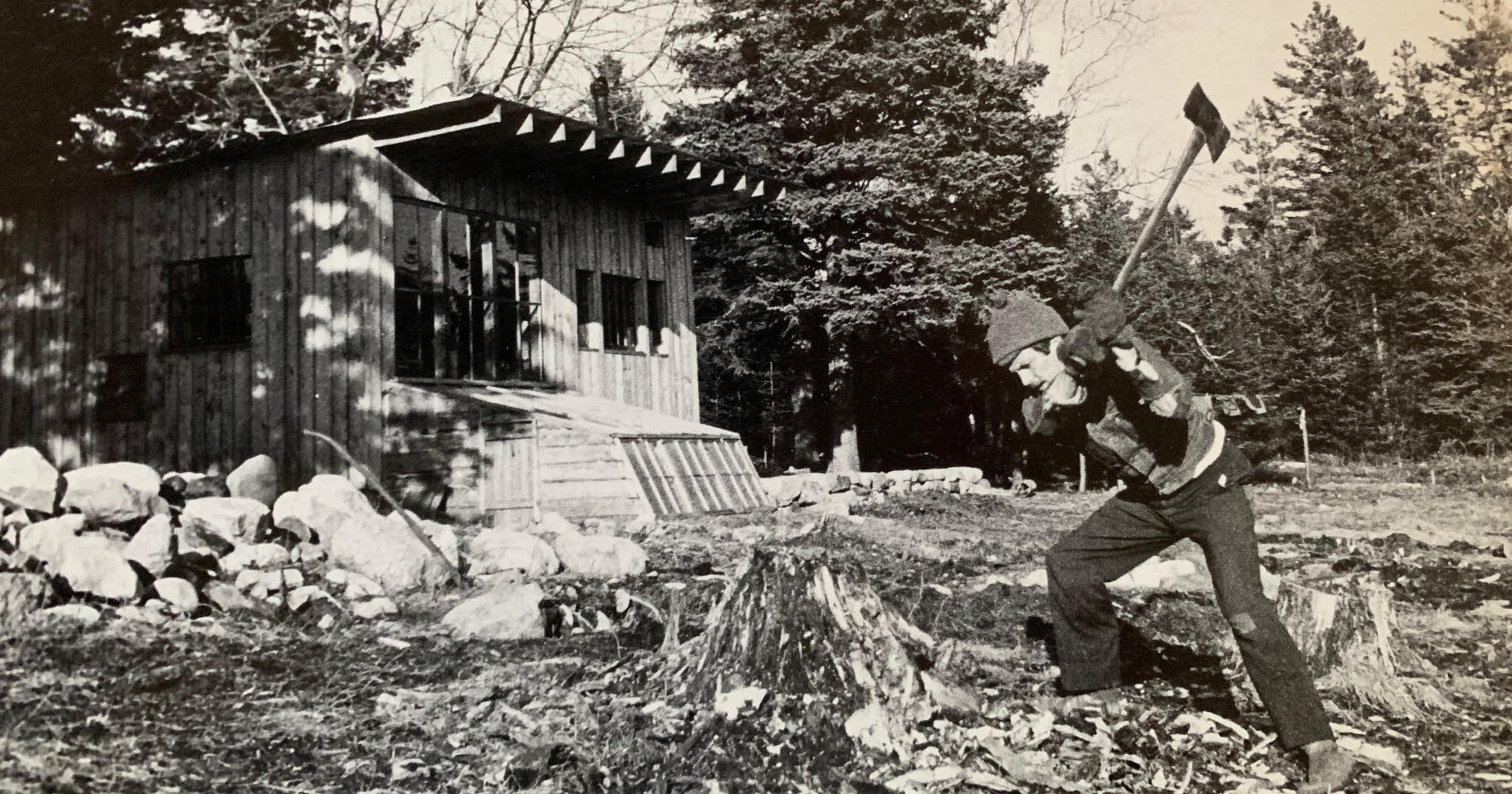

In 2022, when the current strain of avian flu barred live birds from the Lebanon Area Fair, they moved the incubator to McGowan’s studio and live-streamed from there. (McGowan is a photographer, videographer, and co-coordinator of entertainment for the Lebanon Area Fair.) And when the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture announced that live birds would not be invited back for the state’s 2024 Farm Show, McGowan offered his services.

When I arrived at McGowan’s studio on that tempestuous night in January, smack in the middle of the Farm Show week, I found him tending to a chick who had been born the day before with a crooked neck. The head extended from his tiny fuzzy body at an angle, which affected his equilibrium — if not his temperament. When he ran, he did so eagerly in spite of frequently falling over, flailing briefly on the floor of the incubator. McGowan had separated this chick from the others that had been born around the same time because they were bullying him — “chickens are very smart, and ruthless” — and sequestered him to the hatching chamber.

Eve Andrews

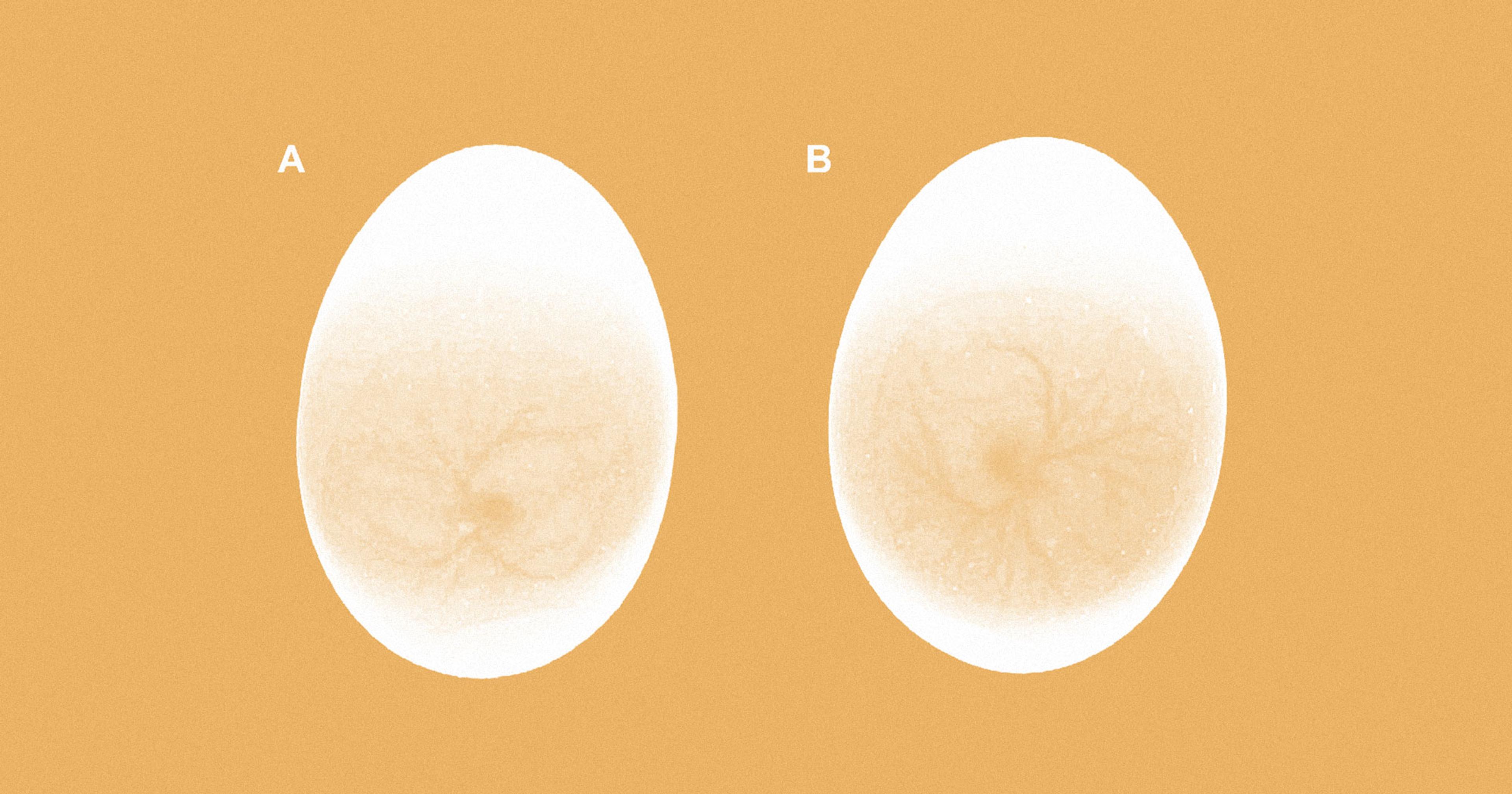

The incubator, carefully constructed in 1998 by the late Lebanon carpenter Ben Bensinger for farm shows past, has two chambers: one in which the eggs hatch, and the other in which the newborn chicks can feed and snuggle together for warmth. Two cameras positioned over each chamber streamed the chicks to both a Facebook feed and a screen at the Farm Show campus, 40 miles away in Harrisburg.

But the hatching chamber was nearly empty, and due to be refilled. McGowan was carefully vacuuming bits of eggshell and excrement from around the off-balance chick when Lape arrived, carrying three trays of fresh eggs that he’d driven over from a nearby hatchery in the torrential downpour. One or two had tiny fissures from where the sharp appendage on a chick’s head — its eggtooth — had started to pierce through the shell, just beginning to push its way out.

The three of us stood around the incubator, watching the chicks chirp and cluster and fall into each other. In the neighboring compartment, a few eggshell fissures expanded, just barely. McGowan was describing how scammers had found his Facebook stream, and were trying to charge people to view what the Farm Show was broadcasting for free.

“It’s amazing, really, with the avian flu and with COVID, it’s created a whole industry of things for protection, protocol,” said McGowan. “It’s almost like when computers came out, and created an industry of virus protection and everything else.

“So it’s something we’ll get used to, and later we’ll look back on history and say: Well, did we do it the right way?”

Eve Andrews

I wanted to see the chicks the way that every other attendee of the Farm Show would see them, so I drove to Harrisburg the following morning. I walked through four expansive halls to get to the poultry section of the show — notably absent of poultry. There was the quietly melancholy wall of chicken photos, a magic show and children’s book reading, a game where you shoot rubber ducks along a chute with a water gun, another game where you fish them out of a kiddie pool, and a six-by-ten-foot screen showing beaming an image of about a dozen white eggs across the crowded room. Many passersby paused to watch and see what would happen on-screen, but many did not.

It wasn’t until several hours later, checking email at a turnpike rest stop, that I learned the eggs delivered to McGowan’s basement the night before had potentially died, and the eggs and newborn chicks that I’d seen on the screen at the Farm Show were from a prerecorded feed. The power outage in McGowan’s neighborhood cut off any streaming capabilities along with the heat source in the incubator.

The following day, McGowan wrote to me to tell me good news: The eggs had survived the cold night, and the chicks were thriving. Avian flu, COVID, and winter storms be damned — the chicks would push themselves into life, beak first, for an audience they’d never see.