Spoiler: You can’t.

Subscribe on your favorite podcast app: Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Pocket Casts, Amazon, or via our RSS feed: (https://feeds.megaphone.fm/onlythingthatlasts).

INTRODUCTION: Making Homestead Happen

[NAT SOUNDS — Morning]

Sarah Mock: The looming 2024 presidential election has gotten me thinking recently, about a time when political campaigns were, well, a little different than they are today.

1984 Ad: It’s morning again in America. Today, more men and women will go to work than at any other moment in our country’s history. With interest rates at about half the record highs of 1980, today 2,000 families today will buy new homes, more than at any time in the last 4 years.

SM: Employment, interest rates, inflation – these are familiar concerns to us in 2024. Even if the level of political optimism here… is not.

1984 Ad: It’s morning again in America. And, under the leadership of President Reagan, our country is prouder, and stronger, and better.

SM: This ad is called “Prouder, Stronger, Better” but is more widely known as “Morning in America.” And was part of Reagan’s re-election campaign in 1984. Since then it’s been touted as one of the most emotionally resonant political ads of all time.

And it helped establish the idea of “morning in America,” a metaphor for peaceful and prosperous renewal, in the American lexicon. In the last 40 years, politicians and media from Marco Rubio and Hillary Clinton to Hulu’s The Handmaid’s Tale have alluded to the idea.

But I’ve been wondering recently, why “morning again in America?” When was the morning before? Though I can’t speak for Ronald Regan or his ad-men, my candidate for the first morning in America would be that era when European settlers stopped thinking of themselves as European. And Americans decided that their continent was the center of a new universe.

I think that was the first time Americans felt prouder, stronger, and better. Like the sun was shining on them for the first time. On that morning was born perhaps the first uniquely American myth. Because if the land beyond the so-called “English seaboard” was going to be the new nation’s destiny, the people needed a hero to lead them into the wilderness.

And so was born the Western yeoman farmer. The agrarian. The pioneer. The homesteader. This patriot was a citizen called to the land, to be self-sufficient and self-reliant through honorable work, democratic ideals, family values, and unimpeachable virtue. This character proved heroic enough to launch a thousand conestoga wagons, and in his footsteps trod more than a million homesteading pioneers and their families.

America’s yeoman era may be largely behind us now, but the wealth they left behind certainly isn’t. The riches that these pioneers were given during the homestead era, specifically in the form of land wealth, still help millions of people buy houses, go to college, and afford healthcare, often without anyone realizing it.

The homesteaders received about 10% of the U.S.’s landmass in direct transfers from the federal government. At today’s average price per farmland acre, that’s something like $1.1 trillion worth of free land. About 25% of American adults in the 21st century count themselves among the recipients of these gifts, as the living descendants of the homesteaders.

At the same time though, this wealth, and the way it’s held, too often hobbles rural school districts, deprives state and federal bodies of resources, and in many ways, threatens the very anti-Feudal ideas that animated the idea of American homesteading in the first place. This paradox of prosperity and poverty will be at the heart of the stories we tackle today – of homesteads past and present, what they’ve created, what they cost, who benefits, and who pays.

This is The Only Thing That Lasts. I’m Sarah Mock.

PART 1: Homestead History

SM: To shepherd us on our journey into the earlier days of American homesteading, meet Rebecca Clarren, a storied journalist, chronicler of the American West, and author of the book The Cost of Free Land.

Rebecca Clarren: I suddenly started to find myself in this American story because my family were homesteaders like millions and millions of other people currently living in America, I am the descendent of people who got free land from the United States.

SM: The land that Rebecca’s ancestors received, as part of the Homestead Act of 1862, was 160-acre plots made available to American citizens, even new immigrants, almost anyone who was willing to go out into the frontier and claim the land themselves. Much like the Kings land grants of colonial America, these parcels were essentially free once the Locke-ian conditions of “improving the land” were met.

The recipients of this land were overwhelmingly white, mostly because the only immigrants who were allowed citizenship in America at the time were “free white persons,” thanks to a 1790 law. And as Rebecca reports, most European immigrants turned out to be, at the very least, “white enough,” like her Jewish ancestors.

RC: So my great great grandparents, Harry and Faige Etke Sinykin, they had six children and they lived in Russia in the late 19th century, at a time when Jews were not allowed to own land… My great-great-grandfather was beaten to within an inch of his life in a pogrom in 1881. As these pogroms are spreading throughout Russia and peasants and Russian soldiers are indiscriminately beating Jews and burning their homes and businesses, many Jews try to get out.

SM: Getting out meant emigrating, and often, emigrating out of Europe altogether. One of those emigrants turned out to be Harry’s younger brother, who is followed shortly by Harry as they both made their way to America, and then Sioux City, Iowa. Once there, like many Jewish immigrants, Harry became a dry goods peddler, carrying a store on a cart or on his back as he walked from farm to farm in rural Iowa and the Dakotas. It was a hard way to earn a living.

RC: He learns at some point that there is free land for the taking in South Dakota, 160 acres that would be his to keep if he can do what was called proving up, turn that wild prairie into farmland and tame it. And, this is family lore that he writes a letter to my great-great-grandmother who’s still in Russia and tell her, “I can get free land, should I do it?” And these are not people that have owned land before. They have no idea what they’re getting into… and she writes to him, “You have poor health, you should do it, this will be good for you.”

SM: In Rebecca’s eyes, there were many reasons the family was likely drawn to homesteading, despite the fact that Harry had never farmed before. It seems certain, for example, that Harry and his family saw taking this leap as a way to “become more American,” to wash away some of their immigrant status by claiming their role in the mythology of heroic nation-building.

The country they hoped to join was none too friendly to Jews, so the prospect of taking their place among those whom contemporary reporters described as “all that was good, all that was real in America,” delivered financial, social, and cultural benefits. So, they did it.

After receiving encouragement from his wife, Harry spent some time living in a cave as he staked and then proved up his claim, a process that required “improving” the land by building a house and planting at least 10 acres within three years. And after five years of living there, the 160 acres was theirs, free and clear. And with the deed in hand, a new world of possibilities opened up for Harry.

RC: Harry gets, it seems like, a mortgage on this quote unquote free land, and it is that money he uses to bring my great-grandmother and her two youngest siblings over from Russia.

SM: Harry got a $900 mortgage against the value of his land, kind of like a modern-day home equity line of credit, meaning that as long as he repaid the total and the interest, he could have the money now and keep the land. In other words, that free land gave him access in 1907 to nearly $30,000 in today’s money.

As Rebecca’s ancestors likely understood it, this land that had become theirs was empty. It was being wasted, and they were doing an important, valuable thing by making it productive. The problem is, making the high, cold plains bloom is actually a lot harder than they might have expected.

RC: 160 acres on the South Dakota prairie was, as an old-timer told me in the Dakotas, that was enough to starve. It is very hard, it’s so dry. This was a time before there were dams or irrigation of any kind. So you’re really reliant on rain to have your crops be successful.

SM: In many ways, this is the paradox of homesteading in America. On the one hand it’s a myth, told to inspire millions to go into unknown and wildly harsh conditions, to do some of the most mentally and physically destructive work imaginable. And in so doing, to “make it,” to pull themselves up by their bootstraps and achieve the kind of self-sufficiency that that life would require.

But on the other hand, actually surviving on the land, in real life, was… almost impossible. When we look into America’s agricultural history, the main group offering any really resistance or critique of the mythology of the yeoman farmer were pro-slavery Southerns, who obviously had their own abhorrent reasons for these challenges.

However, it’s worth considering the non-romanticized view of the homesteader that they offered, which sounds more like Rebecca’s ancestors’ experience than what yeoman myth pushers insisted was the “abundance of all necessaries of substance” that the fantastical garden of the American interior had on offer.

George Fitzhugh, a slave-owning Virginia lawyer wrote in 1857 that, on the contrary:

“Agricultural labor is the most arduous, least respectable, and worst paid labor of all. Nature and philosophy teach all who can to avoid and escape from it, and to pursue less laborious, more respectable, and more lucrative employments. None work in the field who can help it.”

But despite these kinds of arguments, and the lived experiences of so many homesteaders, nothing seemed to stem the flood of new fortune-seekers who turned to the West often to return eastward in only a few years — usually broke, if not broken.

And yet, Rebecca’s ancestors did not starve, despite their arduous labors and lack of abundance. The fact that you can hear her voice is testament to that. So how did they do it? How did they overcome the myriad ways that homesteading threatens to crush its would-be heroes?

That’s after the break.

[AD BREAK]

PART 2: The Homestead Hustle

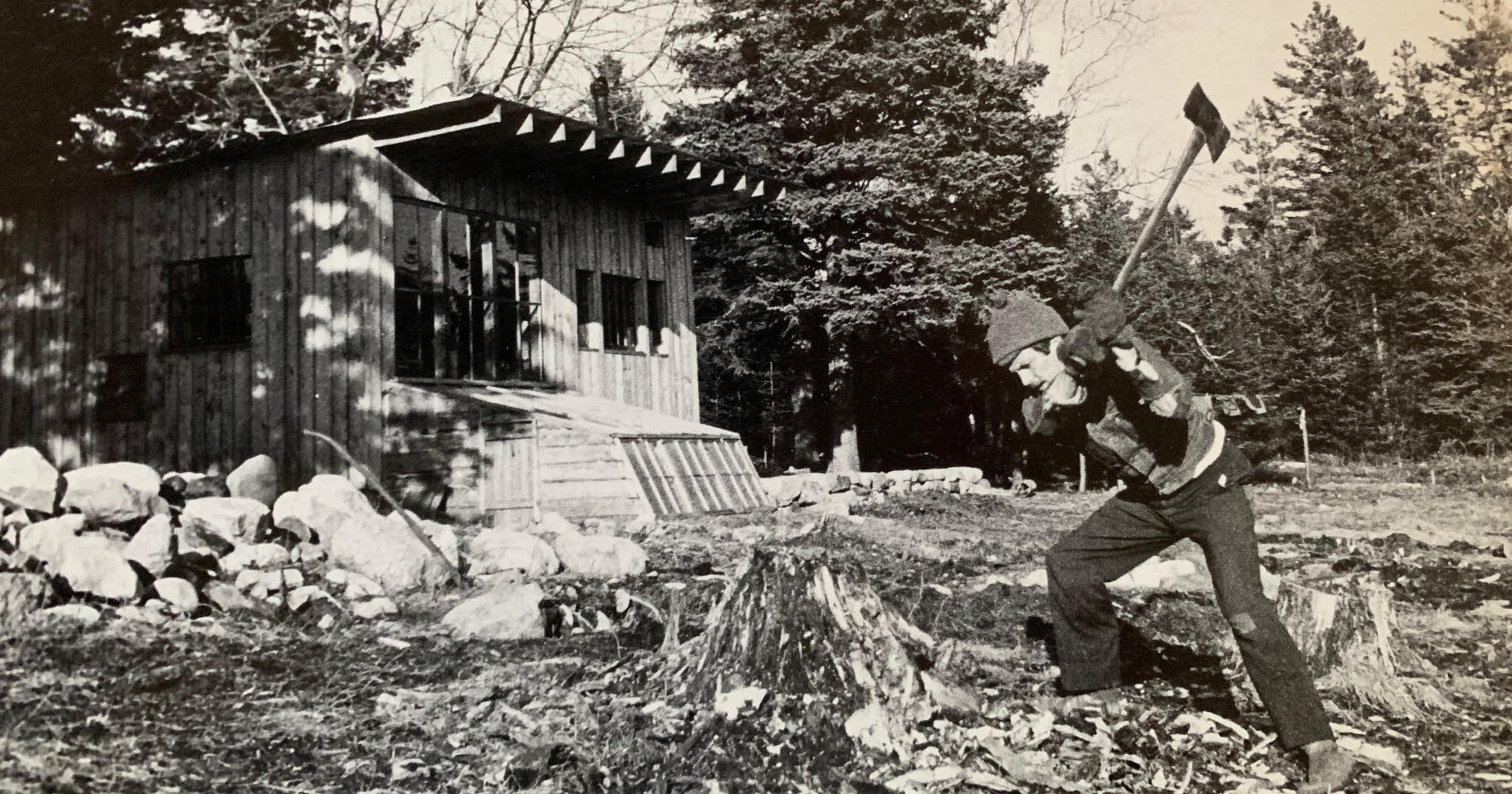

SM: Before we can get to the end of Rebecca’s story, we’ve got to take a brief detour to talk about Kirstin Lie-Nielsen. Kirstin, like Rebecca, is a descendant of homesteaders, but her ancestral yeoman was her mother, who homesteaded in Maine in the 1970s. She was part of the “back to the land” movement, a follower of the political homesteading couple the Neerings, who preached politics of protest and stepping out of the system. And homesteading — which over the decades maintained its core tenets of self-sufficiency and self-reliance — became a powerful way to express this doctrine.

Kirstin Lie-Nielsen: My mother, before she went to be back to the land, she told her grandparents who had been like, self-sufficient farmers out in Missouri, Dust Bowl era farmers, and she was like, “I’m gonna farm like you guys did. This is me connecting with my past.” And she says her grandparents were the only people who were like, “Don’t do that. Why would you do that?” It’s got this romanticism if you haven’t done it and then people who have done it are like, but why?

SM: The romanticism that Kirstin is talking about here, the romanticism of self-sufficient agrarian life, is a powerful part of homesteading mythology. And my conversation with Kirstin offered a lot of insight into what that romanticism might have felt like for Rebecca’s ancestors as they were in the thick of living, or trying to live, the myth. Kirstin has this insight not only because she was raised by homesteaders, but because she is a homesteader herself.

KLN: The lifestyle as a whole was just very appealing. There was a romanticism to it too, of we felt we could do it because we wanted to do it. And we thought we can be self-reliant, self-sustaining, we’ll grow all our own food. And so of course we can do it, because that’s what we want to do.

SM: At its peak, Kirstin’s homestead boasted pigs, sheep, a goat herd, and poultry flock, in addition to an apple orchard and garden. All this bounty was primarily for her and her husband’s own consumption, and for sharing with family and friends, which in Kirstin’s mind is the main differentiator between a homesteader and a farmer. Homesteaders work the land as a lifestyle, rather than to make money. Which almost always means that modern homesteaders, Kirstin included, need regular jobs. Though in Kirstin’s case, they also sell eggs, yarn from the sheep, and other odds and ends to supplement their income.

On top of caring for the plants and animals and a 9-to-5, Kirstin and her husband also built their homestead nearly from scratch. Despite Kirstin’s homesteading mother, she didn’t inherit a family place, so she and her husband tackled buying property, reclaiming fields from trees and shrubs, introducing livestock, and planting their orchard and garden themselves, guided mainly by books and the internet. Only after that did they tackle the house, which had no electricity or running water. They spent several years weathering Maine winters in one heated room, and at least one summer lived entirely in a tent.

Funnily enough, this is exactly the way that the original homesteaders, the pioneers, would have tackled these challenges. Here’s William Doolittle, the retired agricultural geographer from UT Austin who we met last episode:

William Doolittle: When I was in elementary school and maybe when you were in elementary school, we learned of the pioneers moving westward, and the first thing they did was build a log cabin. You think about that for a minute. That would be the dumbest thing they could ever possibly do. You’re moving westward in the early springtime, you’re going to start doing whatever it took to get that crop in the ground. So the first thing these people would have done is do some preliminary clearing. It’s going to be a long, hungry winter if you do it the other way.

SM: But setting the “how to” of homesteading aside, the deeper question of “how,” as in, “how the heck do you even start a homestead in the 21st century?” is a much harder question to answer. As Kirstin emphasized, homesteading is not a lifestyle for the faint of heart, or the light of wallet.

KLN: It’s a very hard lifestyle. I would almost say an impossible lifestyle to thrive at financially. You can probably get by, but you’re probably not putting money away. So your initial cost, just land alone, is going to be a huge expense, and then you have, oh just so much that you have to spend money on…

SM: This fact, the tremendous cash expense of modern homesteading, for everything from property taxes to equipment to fencing to seeds, is the thing that, more than anything else, makes truly self-sufficient homesteading feel so impossible. Radical self-sufficiency today would require giving up things like cell phones, most travel, even gas for the car or tractor, unless maybe, you simply start with a lot of wealth. Yet the modern homestead movement continuous to put tremendous emphasis on self-sufficiency, even when, as Kirstin suspects, there are often hidden resources that belie its existence in even the most famous examples.

KLN: A lot of people who seem to be living, I think, a self-sufficient life may be getting more assistance that they don’t talk about or something like that… Even if you look through history, the Neerings would fly South sometimes in the winter, and then Thoreau with his mother doing his laundry and things like that… true self-sufficiency, very difficult.

SM: Today, Kirstin says, social media has exacerbated the obsession with idealized self-sufficiency. Videos and pictures on Instagram and Tiktok can look whole, complete, and sell a compelling narrative about how blissful, dignified, independence is possible, and also beautiful and fun. But in Kirstin’s experience, this is only ever a small part of the real story.

KLN: A lot of aspects of homesteading are probably true in any lifestyle, but they’re somehow exaggerated… like because homesteading is romanticized and… we want to feel like we have this sort of dream life with the open fields and the cute animals and stuff, I think [it’s] even more tempting to not show the other side of it.... And it’s also, like, a very hard lifestyle and it grinds on you mentally because, you don’t get days off and every day there’s something to do and something to fix and you’re, like, tired all the time… And that part of it is also, it’s hard to even share that at all, but people thinking about coming to this lifestyle who haven’t ground away at it for a few years might just see that oh, like, they’re happy.

SM: What Kirstin is talking about here resonates deeply with what Rebecca learned about her ancestors when she dug into the history that was usually shaded in family lore with only ideas like strength, courage, and freedom. There has always been, and still is today, a shiny exterior, the idea of homesteading as a glorious pursuit, one that hides a more nefarious underbelly of hardship, desperation, and the shame that comes with giving it your all and still coming up short of self-sufficiency.

For Kirstin and her husband, the last few years have meant dealing with euthanizing their poultry flock due to the global avian influenza outbreak, risking Lyme disease to fight the tick population that grows more endemic every year, and struggling against droughts one year, floods the next, and a general unpredictability that makes the lifestyle even more overwhelming to maintain all the time.

For this 30-something couple, these questions about sustainability, about money, physical health, children, and aging, even whether or not they’d be able to leave the homestead even to mourn deaths with their family, have led them to begin to step away from the lifestyle– and the losing battle towards self-sufficiency. And yet, despite everything they’ve experienced, Kirstin doesn’t doubt that the heroic homesteader will continue to inspire new generations to go back to the land.

KLN: There was the movement in the 70s and the movement now, but even, I think if you look through history, there is like a call to this kind of lifestyle… and I think there’s almost like a basic human instinct to try and, if you can, try and grow your own food and there’s a reason we romanticize this lifestyle. There’s something about it that is particularly fulfilling and when you do succeed at it, it really makes you feel, it fills your heart in a unique way.

SM: This almost spiritual call of homesteading, of the desire to care of yourself and your family in some of the most fundamental ways, that makes sense to me. But at the heart of the matter, there’s still that paradox. On the one hand, the idea of homesteading as a self-sufficient and self-reliant way of life for anyone willing to put in the effort. And on the other, the impossibility of self-sufficiency, at least in the absence of existing wealth, which puts this path totally out of reach for so many Americans.

PART 3: What Makes the Difference

SM: And yet, Rebecca’s ancestors survived, not just past their proving up years in the 1900s, but throughout the 20th century. A big part of their secret is something that flies directly in the face of homesteading’s obsession with self-reliance and self-sufficiency on the land. Instead, Rebecca’s ancestors turned to a combination of community reliance, and the time-honored strategy of… not farming the land.

RC: Quickly what my family learns is what many families learn is that in the Dakotas, farming is mostly not going to work. And so they decide to become ranchers.

SM: Though 160 acres was not nearly enough space to run cattle, when the community combined all their plots, and shared the labor of their extended families, it worked. And that’s just want Rebecca’s family did, and from that success, Harry’s wife learned a lesson that has been passed down for generations in her family.

RC: My great-great grandmother would tell her sons, “Not only do you have to be successful in America, you need to become multi-millionaires and the land will be the key to that.” She tells them that on her deathbed. She apparently told one of her sons: “Never sell the land.”

SM: Though Rebecca attributes some of this advice to a concern with sheer safety, the fact that wealth and land offer physical and social security to people who’d fled violence in the past, there was another, very practical reason, never to sell the land.

RC: They also leverage their land for all sorts of other opportunities, which is a very American thing to do.

SM: Leveraging land, or taking out loans against the existing value, or equity, is a kind of financial magic trick, especially when leveraging land that was gotten for free. Of course, leverage involves risk of losing the land if the loan can’t be repaid. But for Harry, leveraging his free land allow him to reunite with his family, and later, helped him access more and more and more economic opportunity.

RC: I pulled every single deed off of my family’s land, and then I pulled every mortgage that my family took out on their land and you start to see a pattern, which was that they would take out a mortgage for a relatively small amount of money on the land, and then they would start a new business that wasn’t reliant on weather.

SM: This savvy strategy would see the extended Sinykin family get into other businesses. First saloons and liquor distribution and later pharmacies, urban real estate, and more, and it would simultaneously help the ranch grow to 6,000 acres by the 1950s.

By Rebecca’s calculations, these mortgages would eventually net the family around $1.1 million, plus an additional $1.3 million in increased land value, when adjusted for inflation. In other words, in less than 100 years, 160 acres of South Dakota prairie became nearly $2.5 million in family wealth. On top of the mortgages, the family got loans and other economic support from the federal government over the years, programs to keep farmers on the prairie despite droughts and dust bowls.

But the relationship between Rebecca’s family and the land does come to an end around 1970 or so, and when descendents approached their elders about selling the land back then, the response was extreme, according to Rebecca’s 91 year-old Aunt Etta.

RC: She described the scene of them coming in and sitting their mother down and saying, we need to sell the land. And my great-grandmother becoming furious because to sell the land, to her and her sister Rose, this was the Good Earth. This was the thing that made them feel American, that made them feel free… even though she didn’t live in the Dakotas anymore, that land shone in her imagination, and in her soul.

[MUSICAL INTERLUDE]

SM: In this way, the homestead era was certainly morning in America for Rebecca’s ancestors. It was their moment to seize a “prouder, stronger, and better” life for themselves and their descendants. And it became a valuable source of intergenerational wealth that would help the family become and remain generally prosperous, secure, and free. Free to move around the country, to pursue their passions, even for one of their heirs to become a journalist– not a career with a lot of “multi-millionaire” potential.

But the true legacy of homesteading, and the homestead era, in the U.S. is not the individual legacy of one family or another, it’s the way this historical moment shaped the nation we are today.

PART 4: The Long Tail of Land Wealth

SM: The systemic impacts of the Homestead Act fly in the face of Kirstin’s experience of homesteading as an exercise in financial vulnerability, because for a brief moment, and only a brief moment, homesteading really was a path to wealth and security.

RC: Thomas Shapiro, who is a sociologist out of Brandeis, he looked at policies like the Homestead Act, and he talked about the Homestead Act as a major source of affirmative action for white people. He says very clearly in his work, if you own a home, if you can send your kids to college, if you own a second home, and you’re a descendant of homesteaders, it is probably because you are a descendant of homesteaders that you can do all those things.

SM: There are as many as 90 million people living in America today who descend from homesteaders. This is where it becomes a little clearer exactly how just 1.5 million hardscrabble homesteads, only big enough to starve, could help America become one of the wealthiest nations in the world.

See, homesteads helped make people wealthy not because they were self-reliant, but because land is valuable, and it was given to people for free. It wasn’t really what was built by the historic homesteaders that mattered, not the crops they planted or the livestock they raised. Their hardships and efforts weren’t really very different from the labor of so many other Americans at the time. But unlike, say, those in factories or domestic workers, homesteaders were given the land they worked to own, and that made all the difference.

Land is wealth: It can be sold for cash, sure, but it’s also way more enduring than that. It can be leveraged for cash again and again, and cash can turn, in every generation, into more education, more entrepreneurial opportunities, and more investments. This, fundamentally, is what Kirstin’s homestead is missing.

If she’d been given land for free, it wouldn’t necessarily solve all her challenges, but it would mean no mortgage payment, and the opportunity to leverage the land to help pay for things like tractor fuel and apple trees. Wealth is, in this way, probably the real key to self-sufficiency she’s missing. The original homesteaders were given that wealth, modern homesteaders are not.

Protecting farmland wealth has also been a major project of state and federal governments, essentially since America was born. I mentioned before that Rebecca’s ancestors received loans and payments from the federal government to help them weather the financial and environmental calamities of the 20th century. That’s one good example of how farmland wealth begets more wealth, but there are many more.

Consider (briefly, I promise) the tax code. Unlike some other kinds of wealth, the way farmland passes between generations is unique. It’s a system called “stepped up basis” which allows people who inherit assets that have grown in value to avoid paying taxes on that increased value.

The process works like this: Say your grandparents bought a farm in 1930 for $400 per acre. At the end of their lives, in 2023, they passed it on to their children. Here’s farmland analyst for Ag Economic Insights Randy Dickhut to explain what happens next.

Randy Dickhut: Fast forward to 2023, and that farm is worth $20,000 an acre. Because they give it through a will or trust mechanism, the next generation, their children who inherit it, they put the value of that farm, the basis, on their books at that time of death. So, they get a stepped up basis, they get it appraised at $20,000 an acre. So they could turn around and sell it today at $20,000 an acre and have no capital gains, no tax implication for selling it.

SM: Stepped up basis is a powerful tool for holding wealth generated from farmland, because the alternative, of gifting someone say, $2 million, by way of 100 acres worth $20,000 each, could result in massive tax implications. On the other hand, the reason the capital gains tax exists is because, essentially, the money a person makes through the appreciation of assets, they make at the moment when the asset is sold, and that’s a type of income — and the federal government taxes income.

For an even simpler example, if I bought a share of stock for $10 and sold it for $100, that $90 is taxable as capital gains. But for farmland, if I held that stock until death, then pass it on, stepped up basis means the tax owed on the $90 goes away.

RD: It’s almost like it’s perpetual if you keep holding it… but it’s also why you see most older landowners, farmers, retired farmers, non-operating owners don’t sell land.

SM: This is only one of many reasons why farmland comes up for sale so infrequently, on average, only once every three generations, and why farmland ownership continues to consolidate. Farms also pay significantly lower state property taxes as compared to any other types of land.

A particularly stark example of how this works: Take Facebook Founder Mark Zuckerburg’s 1,400 acre property in Hawai’i. Zuckerburg avoids hundreds of thousands of dollars of property tax because this particular area is considered agricultural land. One 110-acre parcel of this property, worth about $17 million, nets the people of Hawai’i just $780 a year. This is not outside of the norm for agricultural land.

Famously, in 2016, Donald Trump dodged tens of thousands of dollars in New Jersey property tax by bringing a goat herd onto one of his golf courses, which resulted in it being classified as a farm. Maybe this kind of thing feels like the almost comically absurd – though admittedly discouraging – actions of the accountants of the rich and famous. But it’s not.

Rural schools across the country, who often depend on nearby property tax returns to operate, have faced struggles related to the fact that agricultural land is so lightly taxed. And I’ll say that many farmers and agricultural advocates argue that farmland does not utilize public resources like city water, sewer, sidewalks, streetlights, and the like, and therefore property tax benefits make sense, and if anything, they say, agricultural property taxes should be lower still.

[MUSICAL INTERLUDE]

SM: One thing is clear – farmland, and in particular, the legacy of free farmland, has been a source of tremendous intergenerational wealth over the course of American history. And the funny thing is, that’s one thing that the writers and envisioners of the Homestead Act, and the creators and boosters of the American yeoman hero did not want – at all.

Here’s Jess Shoemaker, a University of Nebraska law professor who’s spent years doing legal research on who owns agricultural land in America – and why:

Jess Shoemaker: If you think about the goals of homesteading… which were about, we’re going to be not feudal. We’re going to not have a dynastic land system. We’re instead going to make land ownership open and accessible to new entrants to farming. We’re going to encourage stewardship, right? We’re going to say that you can become a land title owner if you live in the place and make improvements for some period of time. Because we want to build connections to these places and we want to build this rural community where there’s these agrarian stewards and this kind of Jeffersonian ideal of the new democracy.

And that vision, which was we’re going to break free from feudal land ownership in Europe, where you were born into your class status and you couldn’t change it, that is a part that’s also really failed. And when we look across rural America it looks a lot less like that ideal today than the vision was at the time of homesteading.

SM: In Jess’s mind, this failure was baked in to the legal system of property ownership that the Homestead Act advanced– which required “improvement” at first, and so that the would-be property owners were actually present on the land. But after the “proving up” period, that requirement for improvement, or presence, was gone, and the fee simple property — the full and irrevocable ownership of the land — was forever. This everlasting ownership with its few responsibilities beyond paying property tax ended up recreating the very system that envisioners hoped to prevent.

JS: It’s backfiring, right? It’s backfiring in lots of ways. And so the whole vision, right, was that we weren’t going to have dynastic land ownership, but we’ve built a system where today, if you are not born into the birth lottery of a farm family, or born a billionaire, it’s almost impossible to access farmland now. So instead of this kind of widespread, agrarian, stewarding population across rural landscapes, we see increasing absenteeism, increasing land concentration, all of the things that original homesteading designs were supposed to prevent.

SM: Today, many of modern America’s major landowners are hard to distinguish from European lords. They rent out their lands to tenants, charge for the privilege, and unlike the owners of apartment buildings or retail spaces, don’t even have a depreciating asset to maintain. Farmland owners do not fix lightbulbs or replace roofs, nor is it possible to condemn farmland for lack of care or unsafe conditions.

Plus American farmland has, as a general trend, continued to grow in value since the nation began, so that land that was received for free 100 years ago might sell for as much as $34,000 an acre today. In that way farmland holds and grows wealth in the form of land value and also creates wealth in the form of rent. Or as one farmland researcher and author put it, farmland is “like gold with yield.” Like gold that grows food.

There’s a temptation, though, I think, to kind of shrug at the Homestead Act era and say, “Well, it was a long time ago.” And to look at how few Americans now own farmland and assume that the results of the era have largely come out in the wash of passing decades. But Jess – like Rebecca – questions those assumptions.

JS: I think it’s important to also underline all of the ways in which those initial allocations have legacy consequences today. The fact that the fee simple is perpetual, for example, meant that those first generation allocations had way more weight than they would have if they were a shorter term allocation for a person’s lifetime or with conditions of continued use. Instead, it was a vesting of rights from now until forever with no future rights to really be reallocated or reconsidered for new generations or in new ways.

SM: In other words, because the Homestead Act occurred at a single moment in history, but its benefits, at least the legal ones, were meant to last forever, the values of that historical moment, good and bad, are still locked in to our system of farmland distribution. Though our ideas of equality and equity, of who is worthy of economic opportunity, and of who can claim the title of “American” have evolved a lot since this era, the distribution of land, especially agricultural land, really hasn’t. In America’s agricultural heartland, it still looks an awful lot like 1862.

The legacy of the Homestead Act is not in the past: It’s all around us. And not just because the Homestead Act ended in 1986, when the last tracts of available land in Alaska were claimed. One way the legacy persists is the fact that the vast majority of homestead recipients were white, and that today, 98 % of U.S. farmland owners are also white.

Those two facts are directly related, because property rights, and the wealth they granted, were not given freely to everyone. People of color throughout the country– Native Americans, freed Black folks, Mexicans after the Treaty of Guadalupe, and Asian Americans — were excluded, legally or otherwise, from acquiring property rights, even to land they’d lived on and worked for generations.

In this way, the conclusion of Thomas Shapiro is undeniable. Farmland has, for the preponderance of American history, been a form of wealth freely distributed to almost exclusively white Americans, while being actively stolen from and held out of reach of Americans of color. Farmland helped make the white American middle class a force in world markets, and a model on the world stage, like no other group of non-elites had perhaps ever been before.

But to achieve this, many, many others were forced to move, deprived of kin and culture, and often, reduced to poverty. This history is often forgotten or overlooked today, because of intentional policies to erase the unsavory parts of American history. But also because most Americans are now enough generations removed from the farm that they can’t easily trace the source of wealth and privilege to its agrarian beginnings.

[MUSICAL INTERLUDE]

CONCLUSION

SM: And yet, there’s still that call, what Kirstin called that basic human instinct to romanticize the homesteader lifestyle. I think many might be surprised to learn that this is not nearly as common a romanticism in a lot of other parts of the world.

You read or listen to the stories of peasants from other countries, and I think you’ll find more sound like George Fitzhugh and his proclamation that “none work in the field who can help it,” than like modern-day American homesteaders. But then again, maybe some Americans have good reason to romanticize the homestead era.

Never before or since has such an enormous amount of wealth been up for grabs. Never before had a morning dawned in America so pregnant with potential to change one’s circumstances and fundamentally alter one’s trajectory in life. But for the people and families who remember the stories of ancestors being removed from the land– by force, economic circumstances, or other calamity, this same moment was midnight in America.

JS: It happens through law, right? It’s property as violence that is dispossessing Indigenous people and sort of manifesting this myth of a blank canvas on which new Americans are settling.

SM: How dispossession of farmland drives a legacy of intergenerational poverty in America — next time, on The Only Thing That Lasts.

[SIGN OFF]

SM: Before we sign off, I talked through information from a number of sources and experts today, so if you want to dig into it yourself, check out the shownotes, or our website for links.

While you’re there, make sure you head over to ambrook.com/research to stay up on the latest reporting from the Ambrook team on agriculture, land, and environmental issues like the ones we talk about here on the show. After you subscribe to the podcast, don’t forget to sign up for the newsletter, and follow @AmbrookAg on socials for news about upcoming projects and stories. And we can’t wait to hear what you think! If you like what we’re doing, let us know, and don’t forget to share.

The Only Thing That Lasts is an Ambrook Research production. This podcast is written, produced, and mixed by me, Sarah Mock. Our editor is Jesse Hirsch, with support by Ali Aas and Bijan Stephen. Technical support by Dan Schlosser, and general support by Mackenzie Burnett and the whole team at Ambrook.

A final note, Ambrook Research, the media outlet that produced this podcast, is 100% editorially independent from Ambrook, the fintech company that funds it.