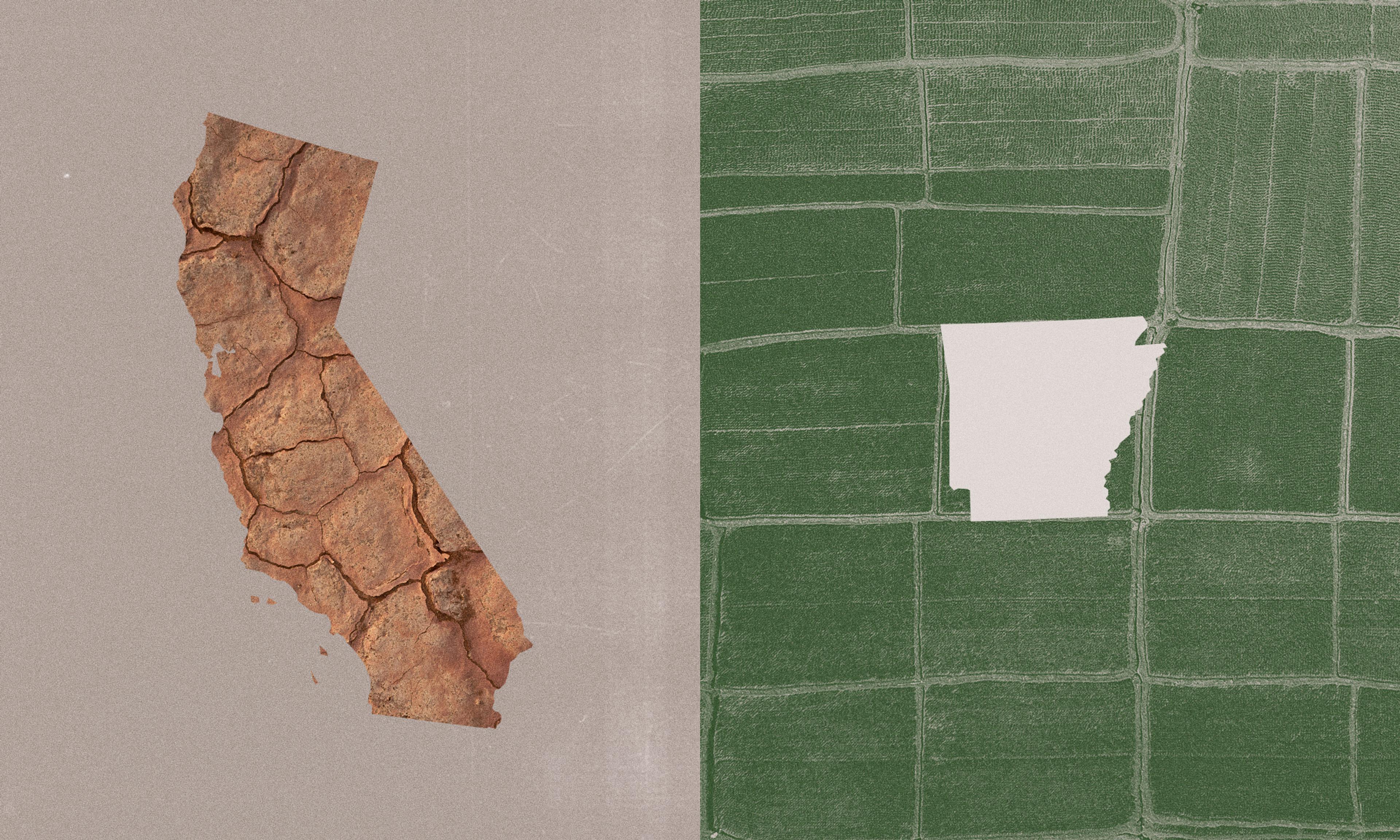

A new initiative aims to shift some crop production from increasingly water-scarce, heat- and fire-scorched California to the Mid-Delta. Rice is key to the plan.

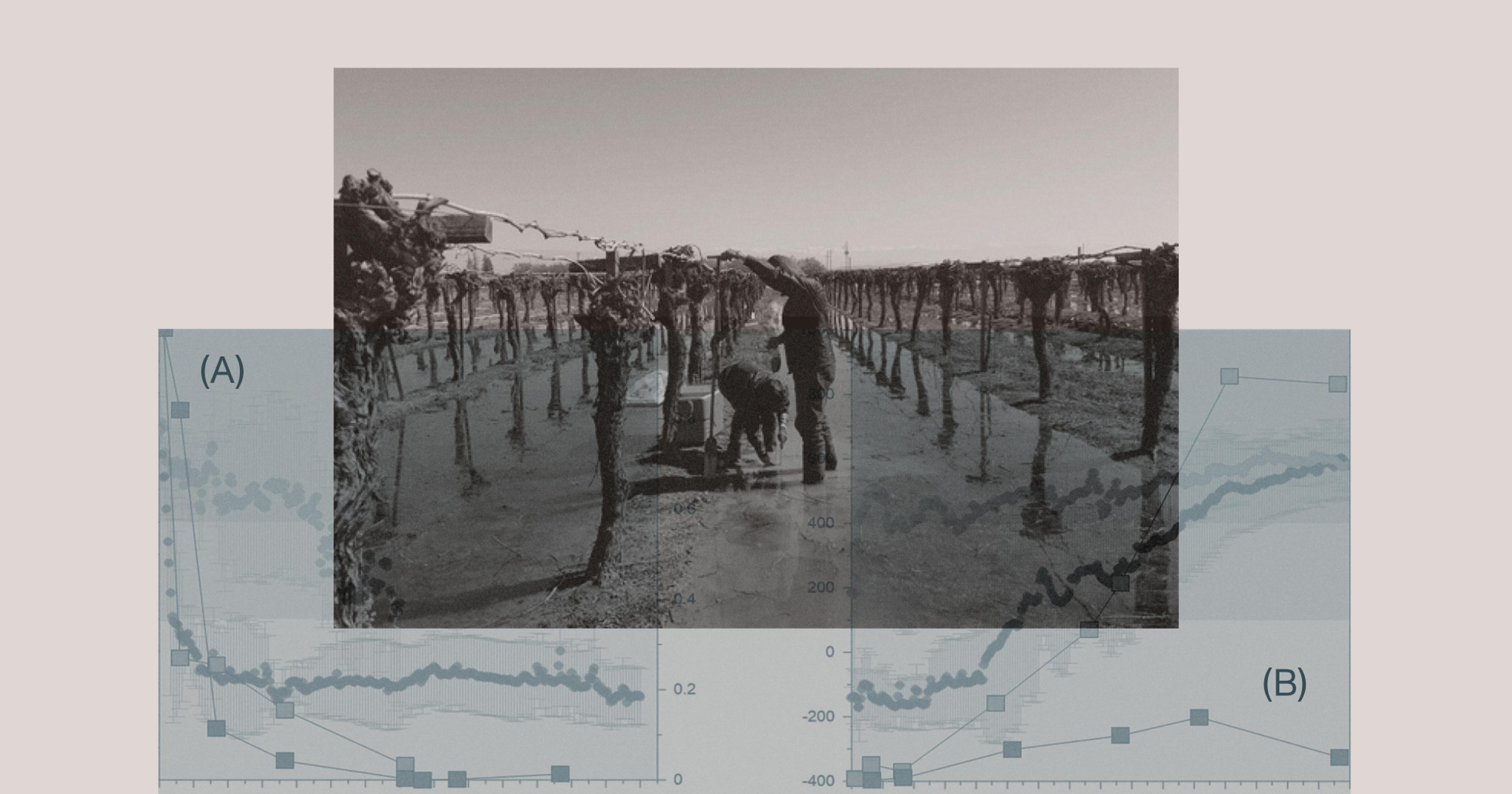

The thick, squelching mud means there’s no outrunning the mosquitoes, which pierce any bit of skin left un-doused by bug repellant. Still, the discomfort of slogging through flooded Arkansas rice fields in the sticky month of June is offset by visions of abundance. A few glistening inches of water lie across several paddies on Hallie Shoffner’s 2,000-acre seed farm, Delta Harvest, from which thousands of bright green stalks of specialty rice protrude. An assistant stands on a metal levee bridge perched above the wet, taking measurements — part of a U.S. Department of Agriculture partnership pilot to determine how much methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrous oxide these fields are generating. When the pilot wraps up at the end of next year, Shoffner will share the results, for free, with any producer who’s interested.

“We want to democratize climate-friendly data for small farmers” who can’t afford to conduct such trials on their own, Shoffner said. But this is just one part of her much bigger plan. That is, to create a market for sustainably produced specialty rice grown across the Mississippi Delta. If “we can say to [buyers], we have this variety grown in these environments that give you these [lower] percentages of greenhouse gas emissions, we can also say, these are unique attributes that we should be compensated for.”

Shoffner believes that using more valuable crops could generate increased revenue for smaller, disenfranchised farms — specifically those that are women- and Black-owned, which comprise 9% and 1.3% of U.S. farms respectively — and help break them out of commodity rice production; it’s an industry that heavily favors large-scale growers who can produce enough of the crop to make a decent income. “Even without doing climate-friendly [practices], specialty rice can bring a farmer 12 to 20% more revenue per acre,” she said.

Shoffner’s efforts stand on their own. But they are also nestled within an even more monumental goal, spearheaded by World Wildlife Fund (WWF), to shift some crop production from increasingly water-scarce, heat- and fire-scorched California to the Mid-Delta. Called The Next California, WWF’s plan is not to steal fruit, vegetable, nut, and grain production from the Golden State. Rather, it presumes that climate change will make it impossible for California to continue producing all its customary crops — that state’s water-dependent farmers will need an out, and it might be soon.

“We wanted to look at what crops are best suited to the Delta and on the flip side, least suited to California,” said Julia Kurnik, senior director of innovation start-ups for WWF’s Markets Institute. By proactively orchestrating some shift to this region, and looping in eager growers like Shoffner, WWF hopes to avoid the land conversion that sometimes comes with starting to grow other crops in other places, as well as its negative ecosystem effects. In the process the nonprofit would like to bolster more sustainable and equitable farming processes, too. Specialty rice is first in line.

Traditionally, rice is a water-intensive crop that requires fields to remain flooded during a growing season, to suppress weeds. California has struggled in the last few years to maintain production on a half-million acres of mostly medium-grain specialty sushi varieties. Although its rice farmers had enough water to sow most of their acreage this and last year, in 2022 production hit a 64-year low after drought decimated water allotments. It’s the kind of event experts say will definitely recur, and with greater frequency.

Much of the Mississippi Delta, however, has water to spare. In fact, rice planting was late in some parts this year, because rains and flooding prevented farmers from getting seeds in the ground. Partly because of all this moisture, for some 50 years Arkansas has been the top rice-producing state in the U.S. It annually harvests about 1.4 million acres worth of long- and medium-grain white commodity rice — that is, effectively anonymous varietals that have no “identity preservation” like Carolina gold or basmati. Growers sell their harvests at a low wholesale rate to local mills, where they’re mixed in bins with other varieties.

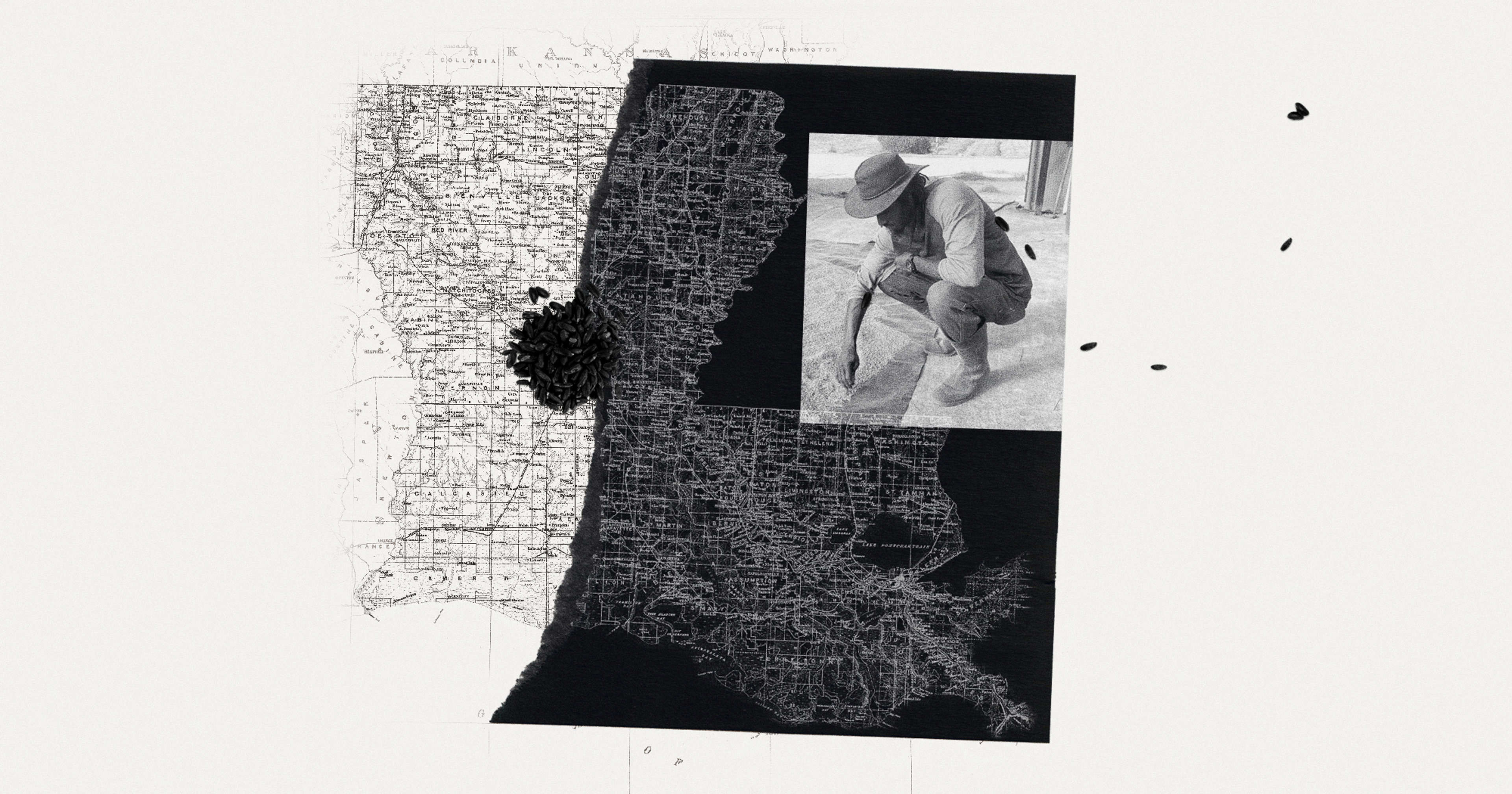

Hallie Shoffner in one of her rice paddies

·Photo by Lela Nargi

“You cannot turn a profit with your standard commodity row crops unless you have huge acreage,” explained Kurnik. Shoffner’s 2,000 acres may sound enormous by Northeast standards. However, “Our neighbors, they have 8,000, 10,000, 20,000 acres,” she said. The only way to get a mill to buy smaller amounts of specialty rice is for Shoffner to team up with other small growers — in the Delta they tend to be Black and by necessity, “scrappier, to turn a profit,” in Kurnik’s words — and sell as one entity. That’s where Delta Harvest comes in.

Delta Harvest (formerly Foodwise Farms) is the name both of Shoffner’s physical farm and her collaboration with five Black farmers to create a supply chain. In this latter capacity, it’s working with several mills and buyers to start to generate a market for its products. And it recently secured its first (still hush-hush) buyer contract for climate-friendly Delta rice that will come online in 2025.

Arkansas’s long history with rice production means that getting its farmers to grow specialty rice is a lighter lift than, say, getting them to grow tomatoes. Delta farmers have both generational experience with rice and some equipment and infrastructure to get it from field to consumer. “We’re trying to bring this to a commercial level so there are more opportunities to scale and profit for minority farmers,” said Kurnik. Another possible easier-lift crop: peanuts, which use some of the same equipment as the 159 million bushels of soybeans Arkansas produced last year, and thrive in heat.

About 25% of the rice Americans eat is considered specialty — think red, purple, Jasmine, sushi, and a high-amylose variety that’s beneficial to people with diabetes. The U.S. imports about 90% of that. Shoffner calls this “leaving money on the table. Plus, it’s not climate-friendly to import something that you can grow right here.”

Bags of specialty rice at Shoffner's farm

·Photo by Lela Nargi

That climate-friendly piece of Shoffner’s plan could prove essential to specialty rice branding opportunities — and it starts with water. Not least because every time a farmer turns on a water pump to wet her fields, her diesel or electric bill soars. Delta Harvest partner farmer Christi Bland-Miller, who grows 400 acres of rice on her 1,400-acre farm in Sledge, Mississippi, explained, “I want to move toward more innovative climate-smart practices. But margins are tight.”

So, Shoffner’s been experimenting with several methods of cutting water usage (and methane production, which is highest in a traditional flood). She’s got multiple inlet irrigation, where fields are filled simultaneously rather than by cascade, where water trickles from one field on to the next then the next; this practice tends to over-water the first field while the last waits (and withers) for its portion. She’s got alternate wetting and drying, where fields are flooded then allowed to dry before being flooded again. She’s got row rice planted in furrows and rotated with soybeans, which gets much more minimally irrigated using polypipe (the tradeoff: higher nitrous oxide production). Shoffner will share data from all of these growing methods as well.

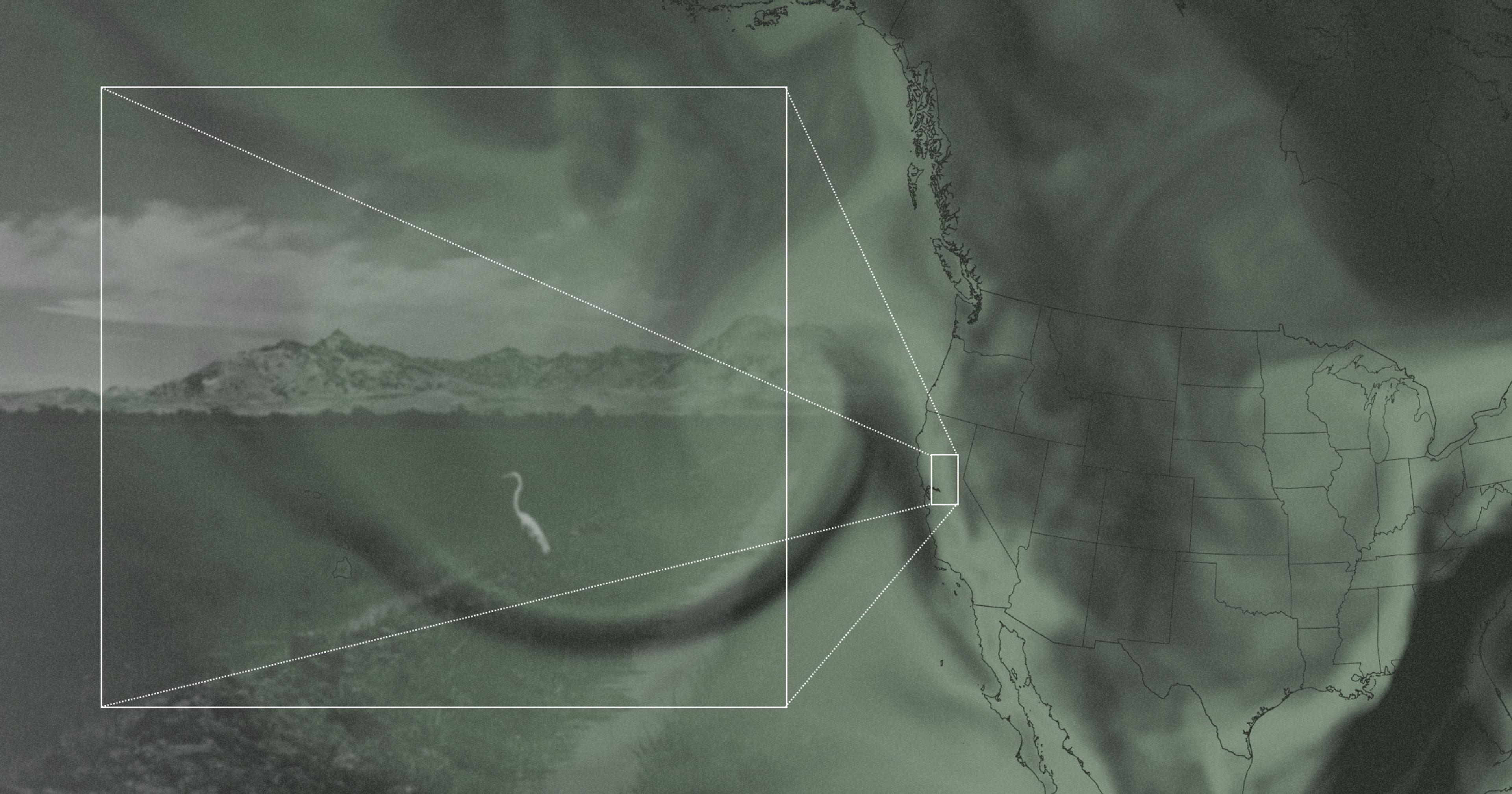

She’s also intrigued by a pilot being run at USDA’s Dale Bumpers Rice Research Center in Stuttgart, Arkansas, where Yulin Jia, the center’s director, has introduced koi to flooded fields of a medium-grain rice called Eclipse. He explained that the fish eat weeds and fertilize rice paddies with their poop, potentially minimizing the need for expensive chemical inputs, which smaller operations can struggle to afford. Additionally, farmers might be able to sell the fish as pond ornamentals, for an additional revenue stream. Dale Bumpers researchers are also instrumental in evaluating rice varieties that might withstand the Delta’s particular disease and other pressures. Last year’s elevated temperatures and relentless humidity, for example, led to a lot of broken rice grains at harvest — “a disaster,” Jia said.

For all the momentum Shoffner has generated around climate-smart opportunities for under-resourced rice growers, significant hurdles to the shift WWF envisions remain. Those tight margins Bland-Miller referred to make abandoning commodity rice a challenge. One big reason is that each rice variety needs to be kept separate from every other variety to prevent cross-contamination — what she calls a “tedious” process that requires time-consuming combine cleaning as well as new grain storage systems that can cost as much as $500,000.

A plastic coyote guards koi in rice paddies from egrets, at USDA's Dale Bumpers facility

·Photo by Lela Nargi

Water conservation techniques — digging ditches and reservoirs to collect and conserve water, leveling fields to ensure its even distribution — are expensive, too. Julius Handcock is director of the Small Farm Outreach Wetlands and Water Management Center at the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff. The center conducts water management research for rice and other crops, which it shares with socially disadvantaged farmers around the Delta.

Unlike Shoffner and Bland-Miller, some of them are experiencing water scarcity due to continuing drought in Northern Arkansas. Few of them earn enough income to afford water-related operational improvements (let alone, say, koi to release in their fields). And with loans and grants for such upgrades viewed as generally inaccessible to Black-run farms — there’s a long history of accusations of bias against USDA for granting loans to more white farmers than Black — “That means you can’t grow this [rice] crop,” Handcock said. “You have to grow dryland beans or peas, where you don’t need as much water, so you can still make money on your land.”

Bland-Miller, though, sees hope in a USA Rice-Ducks Unlimited Climate Smart Initiative for historically underserved farmers in the Delta — defined as beginning, socially disadvantaged, veteran, and limited resource farmers — funded by USDA and open for enrollment starting this past June. It offers more financial assistance than USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, “for the same practices,” Bland-Miller said. A total of $63 million is available for water efficiency improvements like land leveling, alternate wetting and drying, switching to row rice, pump efficiency evaluation, installing irrigation devices and flow meters, and pump automation.

Shoffner is well aware of the barriers to success for specialty rice farmers in her region. “Farmers like Christi and me, we live on the margins of the ag industry,” she said. But “If we can do identity preservation on a larger scale, and have buyers who are interested in it, we can create a market. On top of that, let’s secure the food supply chain by making sure small farms — women, minorities — stay in business. It’s a great story for buyers. It’s a great story for consumers. It’s a great story for farmers. It works all the way around, if it works.”

Reporting for this piece was supported by a media fellowship from the Nova Institute for Health.