The plant-based drink has exploded in popularity, but low oat stocks put the industry in a “perilous position,” according to experts.

“Oat milk latte!”

“Cappuccino with oat milk!”

A barista’s voice rises above the clamor of a café, as drinks appear on the counter. Scenes like this play out all across America today, with oat milk rapidly catching up with traditional dairy as a caffeinated beverage staple.

The plant-based drink has exploded in popularity in recent years. In roughly the last year, oat milk’s U.S. retail sales ballooned to $695 million, a 28% increase over two years, according to data company SPINS.

Randy Strychar, president of OatInformation — which focuses on oat market research and provides information to traders, millers, and more — said oat milk’s popularity has “taken demand to a new level.”

“Oat milk has certainly been a game changer” for oat crop demand, Strychar said. He estimated the beverage has added between 10% and 15% in additional demand for oats.

Despite the increased need, our fickle oat supply depends on farmers’ incentives and net returns, compared to more established row crops such as corn and soybeans. Demand is growing, but supply is waning due to factors related to the climate and farmers’ motives to grow the crop, putting the oat market in what Strychar described as “a perilous position.”

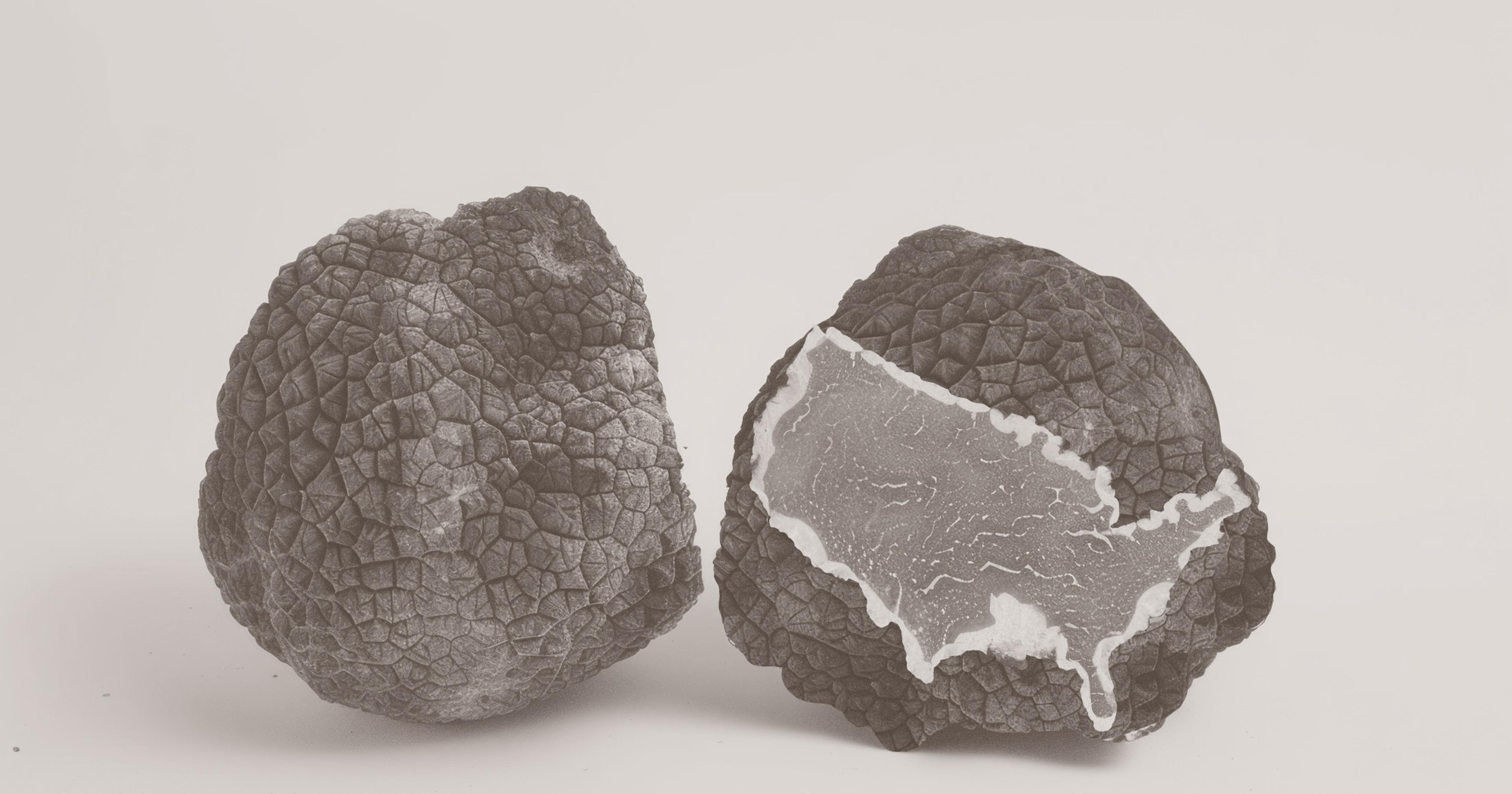

The U.S. is a small oat producer on the world stage, with less than 900,000 metric tons and contributing just 4% of global production. The country imports the majority of its oats from Canada, which is among the world’s largest producers.

But in the Great White North, supply is “down sharply from last year and the previous five-year average, due to a significant decline in production,” wrote Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). AAFC predicts an oat supply of 3.94 million tons for the 2023-2024 season, well down from 5.58 million tons the prior year.

While acreage is up for the 2024-2025 season, total supply and exports are projected to remain the same year-over year, per AAFC. Western Canada has been experiencing a drought, and oat farmers have little buffer stock left from previous years.

“We have no more cushion,” Strychar said.

Can Oat Supply Keep Up With Latte Demand?

It’s not just coffee shops: Demand for oat milk is up in grocery stores, where it held a 24% share of the retail plant-based milk market in 2023, an increase from its 18% share in 2021, according to Ben Pierce, corporate engagement research analyst at the Good Food Institute.

But while oat milk’s growth has significantly increased demand, the predominant use of oats is still for food items such as cereal and granola bars, Strychar said. In general, consumer demand patterns tend to change slowly over time rather than in dramatic swings — in some sense, oat growers are still adjusting to non-traditional new demands.

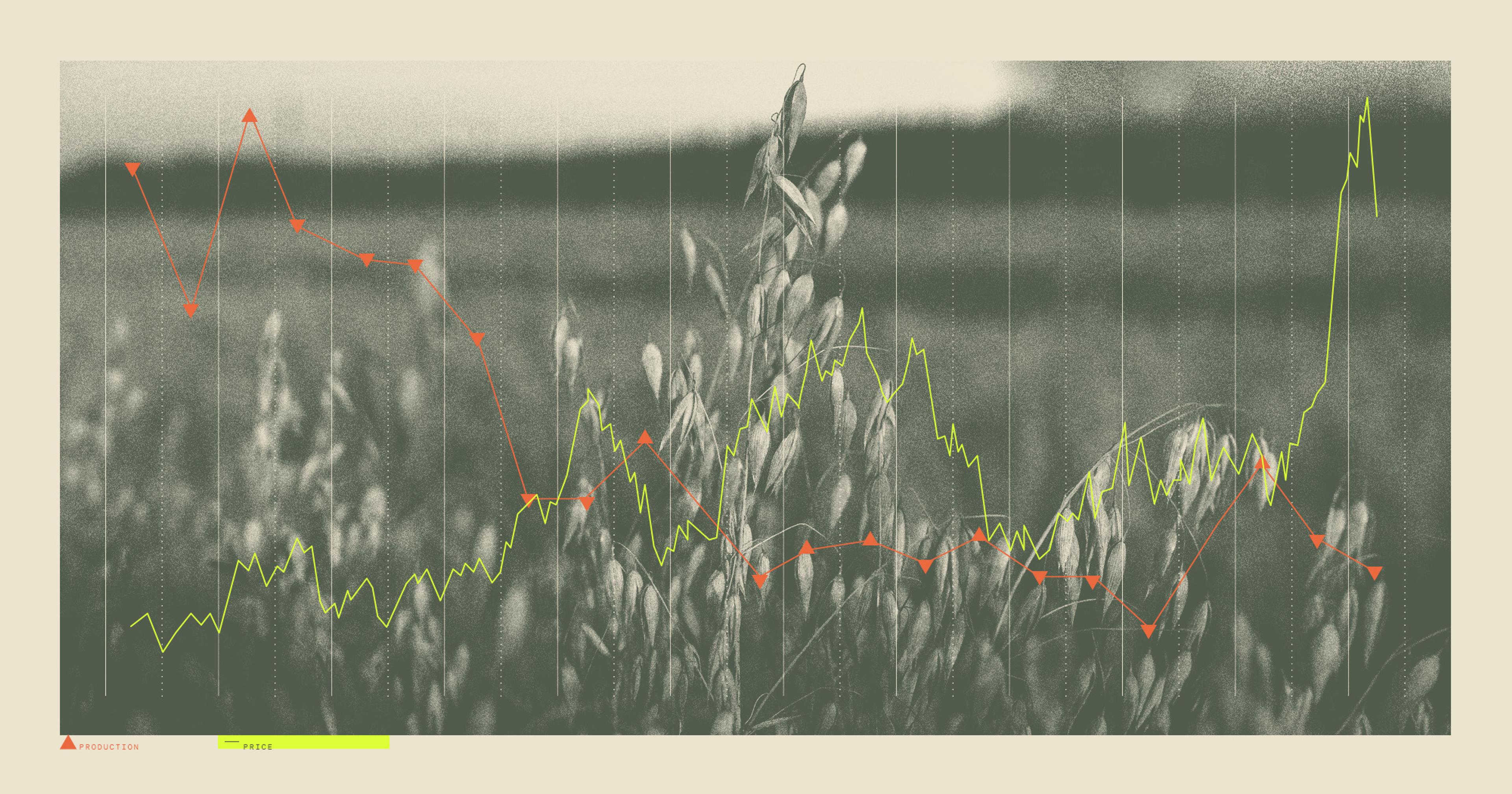

Supply, meanwhile, fluctuates greatly from one season to the next. In 2021, a drought hit Canada and the U.S.

“It really affected the supply,” said Melanie Caffe, associate professor at South Dakota State University who leads the university’s oat breeding program. “The price went up like we had not seen before.”

Stocks in Canada fell by nearly half, and oat prices reached record highs of nearly $8 per bushel in spring 2022. Manufacturers like Oatly faced a strained supply of oats, leading it to raise prices.

Then the following year, oat crops rebounded. Canada had record high oat stocks last July, but it’s on pace for record lows this summer and in 2025, according to Strychar.

“It’s concerning for the food and beverage companies, this up and down on the supply,” he said.

The up and down is ultimately in the hands of oat farmers, Strychar said, and has to do with the net returns they get each year on their crop. If one year the returns are on the lower side, “the farmers just say, ‘I’m not going to grow oats this year,’” Strychar said. Then the supply tapers, the price goes up, and the cycle continues.

Ultimately, however, Strychar believes the ability of oat supply to meet demand — whether it’s for food products or oat milk — is in the hands of manufacturers.

“If a food company needs oats, pay up for it,” Strychar said. “That’s how you stabilize the supplies.”

If the Oat Price Is Right

Like any business, farmers want the best bang for their buck. “If the price goes up, we tend to have more farmers willing to plant oats, which makes sense,” Caffe said.

Dan Voss, a farmer in Iowa, said corn and soybeans are his main crops, while oats are a “sideline.” Voss doesn’t sell the crop to food or beverage producers, but for livestock feed. The crops are slightly different; food and beverage producers seek oats with a heavier test weight compared to the oats used to feed livestock.

On a revenue per acre basis, Voss acknowledged that oats don’t yield as much as corn or soybeans. “But your expenses are so much less,” he said. “You don’t need as high a revenue to make a profit on [oats].”

Seed expenses are lower for oats than corn or soybeans, according to Voss. He also said oats require less fertilizer than other crops, which not only reduces costs but is also beneficial to conservation — an important factor for Voss, who won the 2023 Iowa Conservation Farmer of the Year award. Plus, adding oats into the soybean-corn rotation aids soil health: Oats serve as a cover crop.

Yet Voss is an exception in his region. Very few neighboring farms plant oats — a change from 60 years ago, when Iowa harvested more than four million acres of oats, according to the Iowa Farm Bureau. Today, the state only harvests around 40,000 acres.

Even with those declines, Iowa, along with Minnesota and the Dakotas, are among the top oat producing states in the U.S. But it’s a sharp drop from years ago. In North America, Canada continues to dominate oat production despite declines in the latest harvest.

Reversing the Oat Decline

The U.S. government has not subsidized oat planting in the same way it has corn and soybeans. The U.S. Farm Bill has typically focused crop insurance and income support on crops such as corn, soybeans, and wheat.

This means that unlike corn and soybeans, farmers haven’t historically had a good way to insure their oat crops. That changed in late 2022, when the U.S. Department of Agriculture expanded its Small Grains Crop Provisions to offer revenue protection for spring oats for the 2023 crop year.

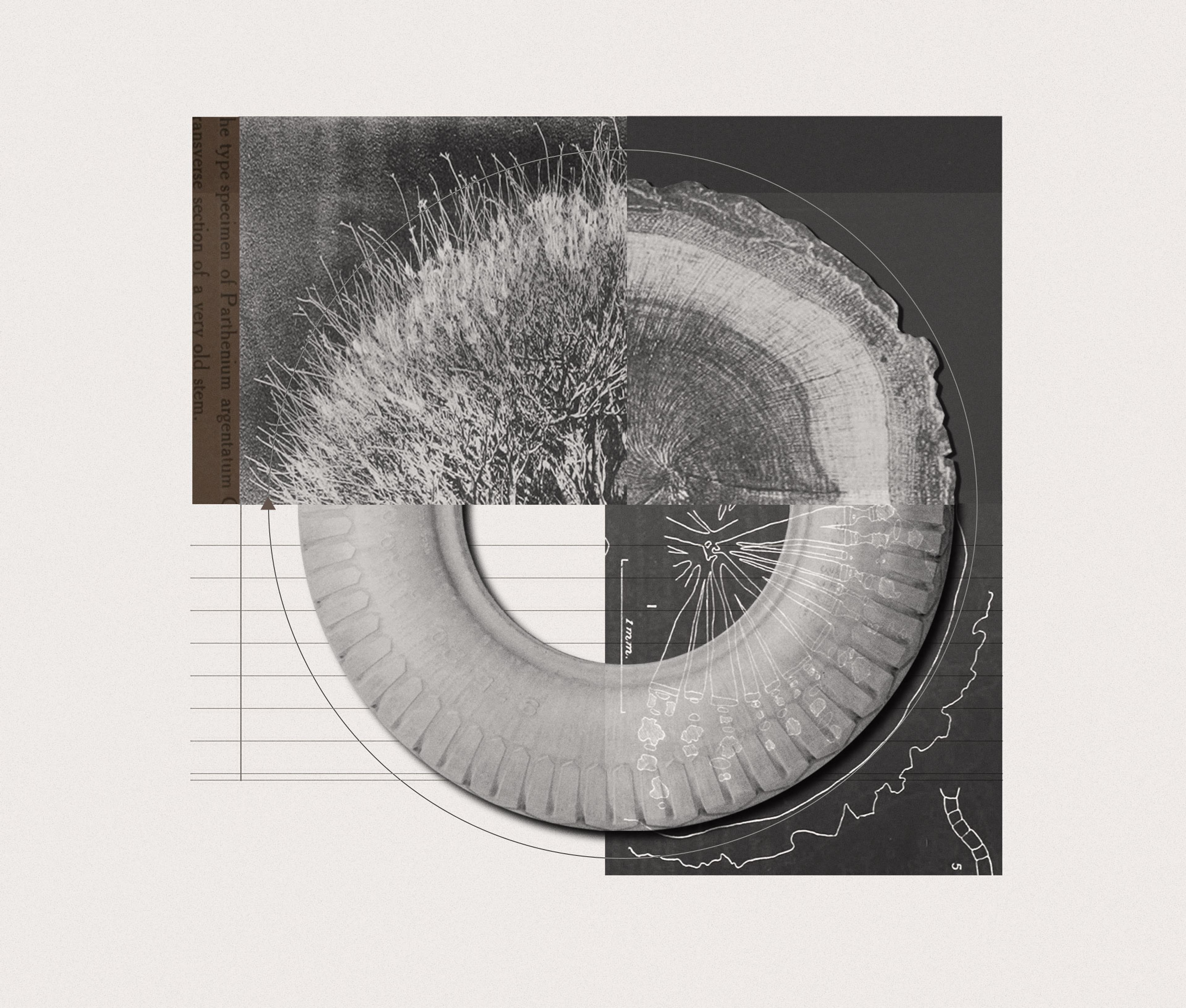

Researchers are currently developing varietals that make the crop more appealing to farmers. Caffe’s breeding program looks at characteristics such as increased yield, higher protein content, and drought and disease resistance, among others.

Parts of the private sector are taking matters into their own hands to incentivize oat planting. Oatly launched a pilot program with U.S. farmers. The company said on its website — Oatly did not respond to requests for comment — the program could bring new income sources to farmers, healthier soil due to crop rotation and a sustainable supply of oats.

“They’ve been a good crop for me,” Voss said.