Grocery giant Kroger is expected to merge with Albertsons, further shrinking the pool of retail markets for farmers to sell to.

It’s easy to see why the proposed Kroger-Albertsons mega-merger would be unpopular among consumer advocates — grocery retail inflation is already high due to ongoing supply chain issues, staffing shortages, last year’s deadly avian flu outbreak, the war in Ukraine, and other erratic changes. But why are farmers and farmworkers so concerned? A growing group of agriculture associations is fighting to make their voices heard.

In October, the Kroger Company agreed to buy Albertsons for $34.10 per share, for a deal valued at about $24.6 billion. Kroger, which operates grocery banners such as Ralphs, City Market, Harris Teeter, and others in 35 states, is the country’s second-largest grocery. Albertsons — whose subsidiaries include Acme Markets, Kings, and Safeway — is the fourth-largest, after Costco. Combined, the retailers would account for 15.6% of the U.S. grocery market share, second only to Walmart, which captures $1 out of every $3 spent at American grocery retailers.

According to Kroger’s official statement, the merger is expected to enhance competition, “relieve the inflationary pressures facing shoppers,” and further advance the company’s mission by “expanding our footprint into new geographies” and providing “fresh and affordable food” options.

Sounds nice, but farm groups aren’t buying it.

In early December, the National Family Farm Coalition, National Farmers Union, Farm Action, and an assortment of regional grower associations sent a letter to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) expressing their opposition to the merger, which they said would “create a new mega-grocery buyer with exceptional buyer power to squeeze its suppliers, shrinking farmers’ and workers’ share of the food dollar.”

Some worry that Kroger-Albertsons’ buying power would leave farmers with little room for contract negotiation.

A few weeks later, a host of grower associations representing farmers in the Western U.S., where the merger could cause conflicts with overlapping markets — Western Growers, the California Fresh Fruit Association, and Colorado Fruit & Vegetable Growers Association — submitted an additional letter to the FTC. In it, the groups pointed to the Albertsons’ acquisition of Safeway in 2015 — after which the company awarded contracts only to its largest produce suppliers, leaving smaller farmers to sell elsewhere — as an example of the negative outcomes that can be expected with a merger of this size.

Those who oppose the merger worry that Kroger-Albertsons’ buying power would leave farmers with little to no room for contract negotiation. If they’re not able to supply the amount of produce needed, or they’re not able to supply it year round, the mega-grocer will find somebody else who can — even if they have to go overseas to do so. This sort of “take it or leave it” contract would be a huge blow to American farmers of all kinds.

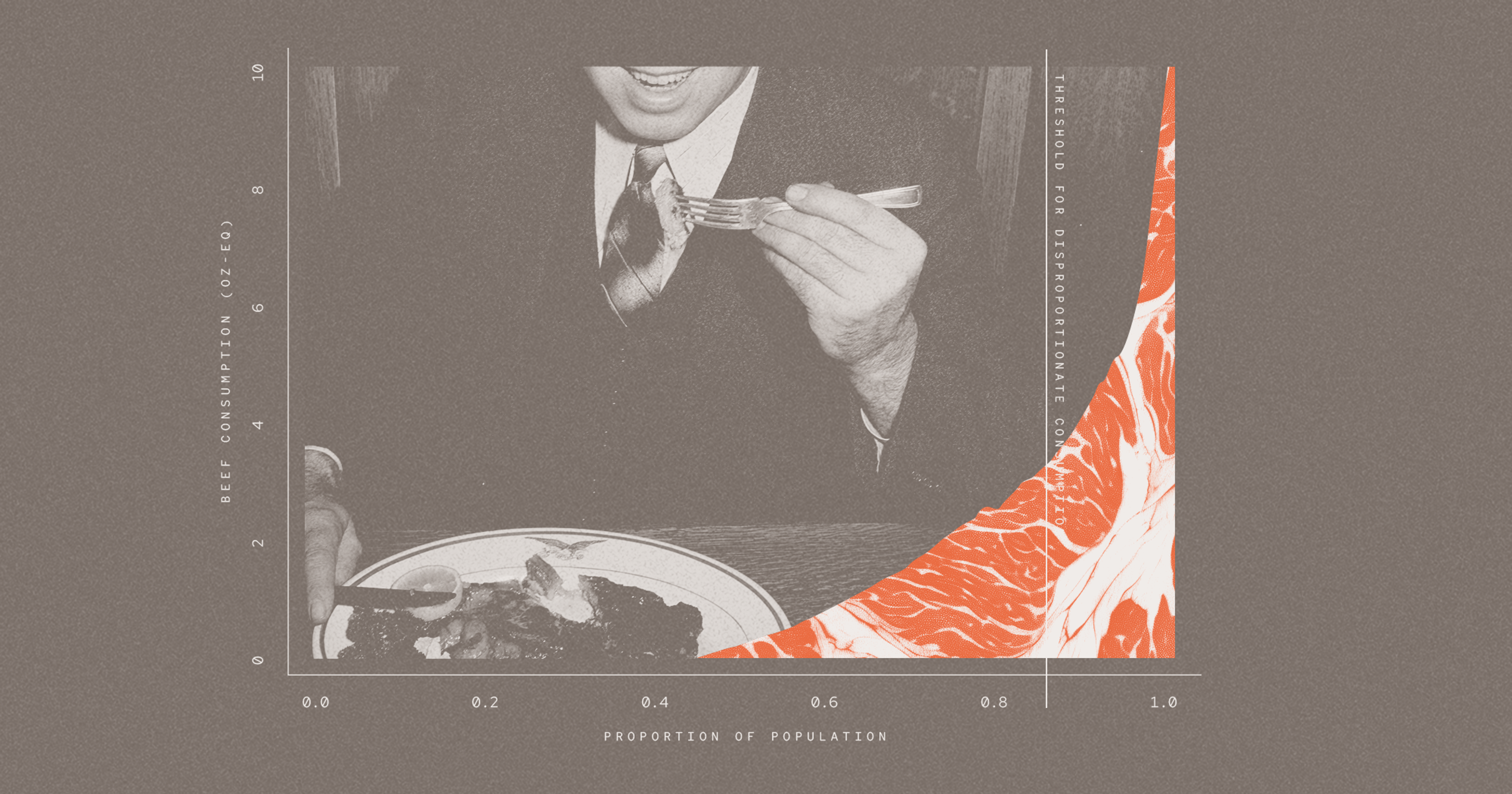

Smaller farms, which have already struggled with the cycle of supermarket consolidation seen in recent years, are in crisis. Farmers routinely sell their crops for less than what it costs to produce them. The pressure of farming with such small margins has led “members to farm less acreage, move production to other countries when feasible, or leave farming altogether,” the letter from the Western grower groups read. If the Kroger-Albertsons merger is allowed to continue, competition among buyers will shrink, leaving farmers with fewer customers (in this case, grocery retailers) to work with. As third-generation Georgia Vidalia onion grower Shad Dasher told Civil Eats, “the circle is getting smaller and smaller to sell to.”

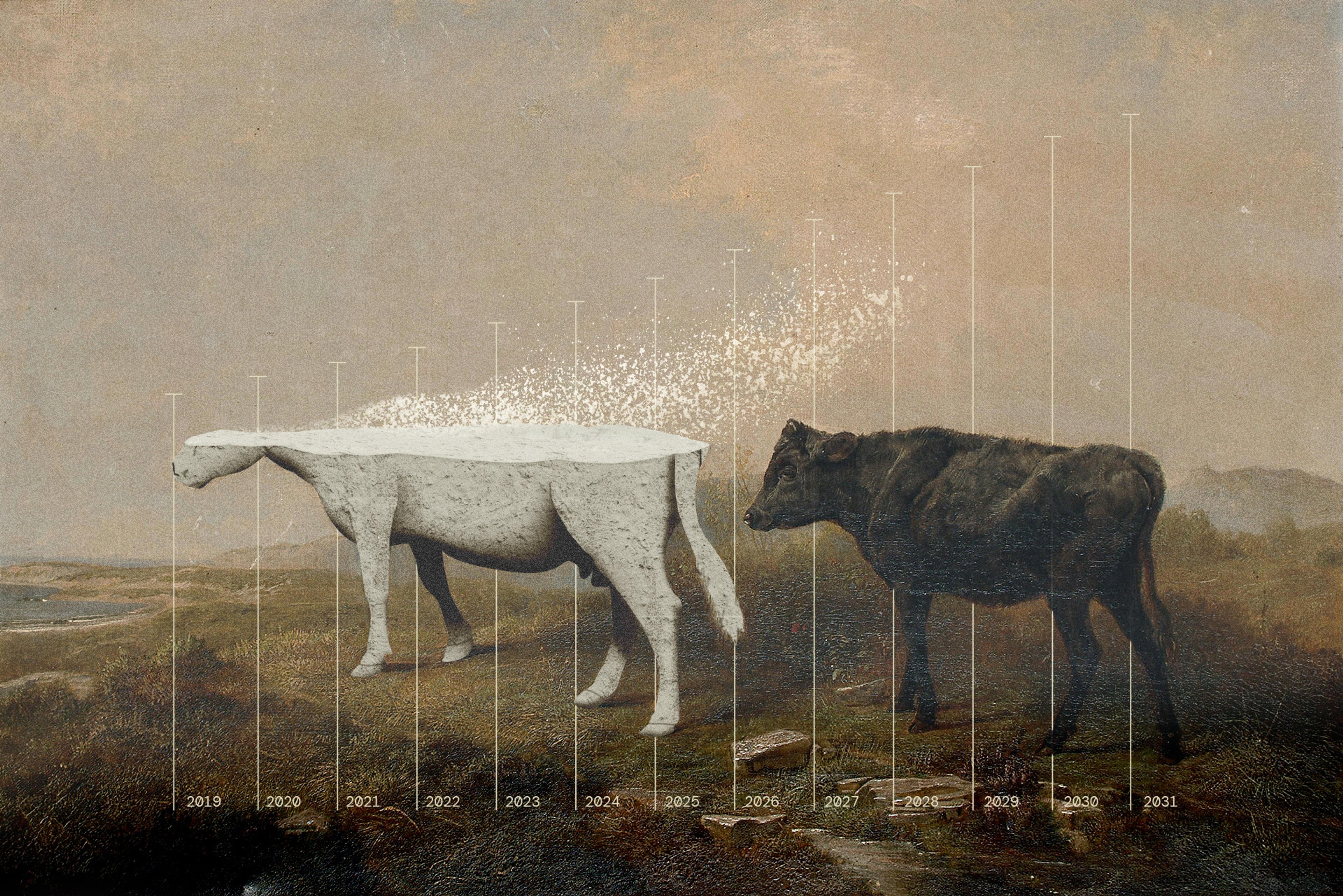

Despite most produce being seasonal, only grown during specific windows, the biggest grocery chains insist that farmers can provide year-round supplies. For example, asparagus is a spring vegetable, but consumers expect grocery stores to have those green stalks stocked at all times. And stores such as Kroger require the farms they contract with to always be able to supply them — even if the domestic farmers have to import the produce from other hemispheres. As Dasher explained to Civil Eats, “Growers [were told] directly that they could either start importing sweet onions from South America in the off season themselves, or the store would bypass them and buy from elsewhere.”

The trade organizations that oppose the merger emphasize the harm done to American farmers as grocery retailers continue to source more foreign producers, “who are ready, willing and able to undercut American producers on operating costs and price they will accept from the retailer … That is harmful for farmers, farmworkers and rural communities that depend on a robust agriculture industry.”

“The buying power of the newly combined Kroger entity cannot be understated.”

Just before the Thanksgiving holiday, lawmakers called on the FTC to “closely evaluate” the Kroger-Albertsons merger deal. “This acquisition threatens to create competition-stifling concentration in markets across the country, hurting consumers, workers and small businesses,” the letter said.

In November, attorneys general in California and five other states filed lawsuits to stop Albertsons’ from paying nearly $4 billion to its shareholders until regulatory review could be completed, but the federal court declined to review the case. Shortly after, a Washington court issued a temporary restraining order, which was lifted yesterday.

While not opposed to the Kroger-Albertsons merger, even the National Grocers Association (NGA) has expressed concerns about grocery consolidation, “which has enabled dominant grocers to use their economic power to disadvantage smaller competitors and shut out rivals,” said Laura Strange, senior vice president of communications and external affairs at NGA. The merger “will only increase the influence that a handful of grocery power buyers wield over food suppliers unless clear guardrails are in place that limit their market power.”

Farmers and farmworkers aren’t the only ones who stand to lose big in this situation. Grocery workers do, too. “Profiteering stands out at Kroger and Albertsons, with profits far outpacing worker wage growth or the cost of food. Their outsize price hikes are at least partially responsible for inflation. Even while they were competing with each other, these companies jacked up prices and had record profits,” wrote Daniel Fleming and Judy Wood in an op-ed in CalMatters. They estimate the total job loss in the Los Angeles region alone will be close to 5,750 jobs. “If they merge and no longer have to compete with each other, they will be less constrained and free to be more rapacious.”

As the letter written by the Western grower groups emphasized, “The buying power of the newly combined Kroger entity cannot be understated.”