High cost of health care and unpredictable year-to-year incomes have strained farmers’ ability to access health insurance nationwide. Minnesota has a new plan.

Minnesota farmer Cindy VanDerPol had her last doctor’s appointment to check the progression of her breast cancer in April. The timing was fortunate — it was right before her family got kicked off their health insurance in May.

VanDerPol, who runs Pastures a Plenty, a third-generation livestock and organic alfalfa farm with her husband, has been farming for more than two decades. Access to affordable health care has been a struggle the entire time.

Farming is a dangerous job, compounded by the typical lack of access to affordable health insurance. As largely self-employed individuals, farmers have no access to work-based insurance, leaving them subject to marketplace prices. According to a 2015 study, 65% of commercial farmers named health insurance as a serious threat to their farm’s livelihood.

On May 24, Minnesota passed legislation hoping to address this problem, for farmers and other Minnesotans without access to affordable health care through their workplace. Minnesota is one of two states — joined only by New York — that adopted a state-administered health care option, called MinnesotaCare, which is available to residents with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level, but earn too much to qualify for Medicaid. Now, thanks to the new legislation, even more Minnesota residents will have access to that program.

This option will change the lives of farmers like the VanDerPols, who have fluctuated between insured and uninsured for years. During the pandemic, they were able to stay on MinnesotaCare thanks to special protocols that inhibited the insurance from kicking individuals off regardless of income increases. Without that, VanDerPol said her cancer treatment bills would have bankrupted the farm. Now, the moratorium has ended, and the VanDerPols are uninsured again.

“Hopefully, in September, when I have my next appointment, I’ll have insurance. Fingers crossed,” she said. As of now though, their on-paper income is too high to qualify for any programs they could afford. “Our income last year looked good on paper, but not in the checkbook.”

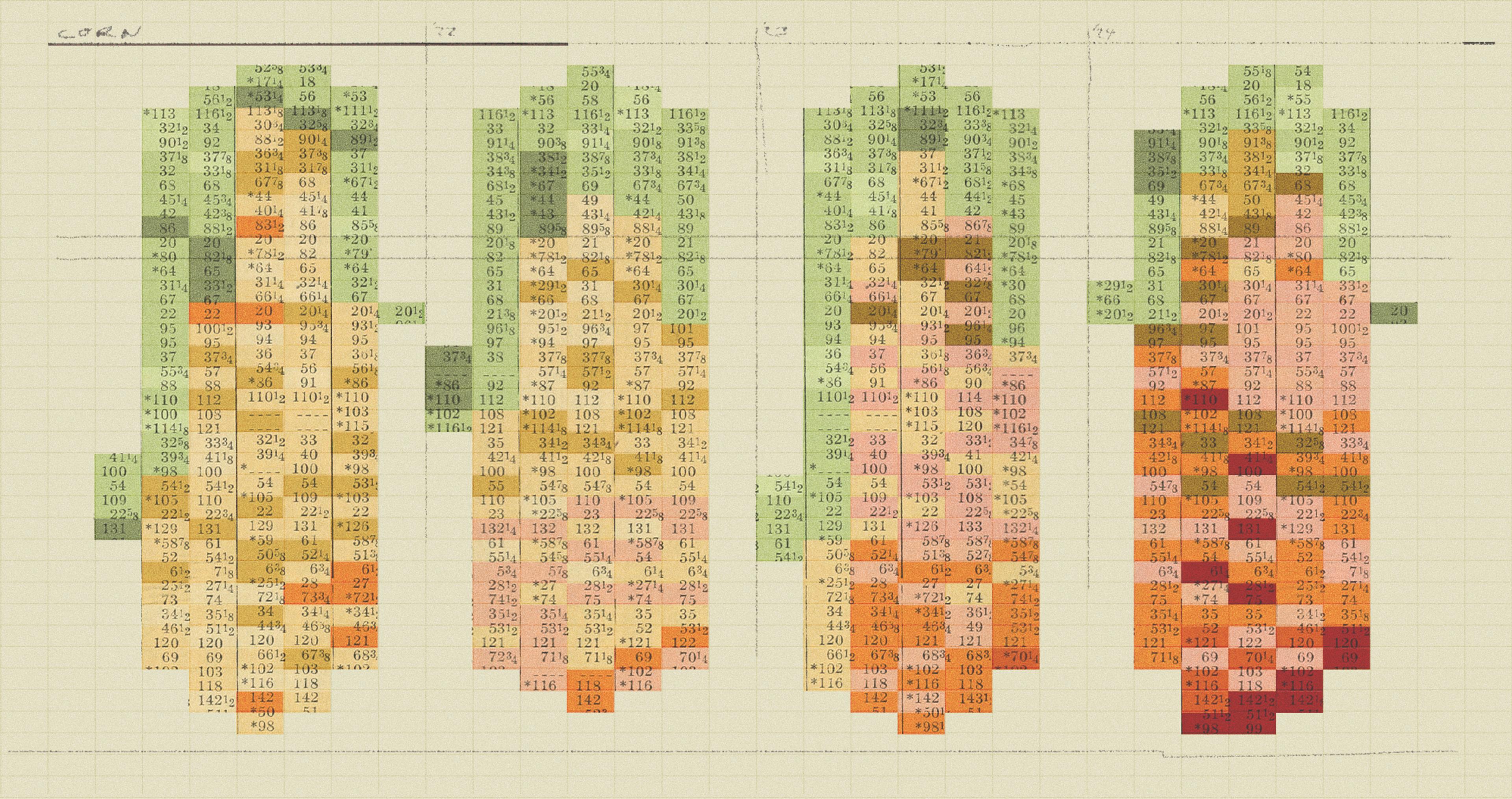

The new bill offers something called the MinnesotaCare Public Option, which allows more Minnesota residents the chance to buy into MinnesotaCare. Instead of the current income cap for MinnesotaCare coverage — $27,180 per year for an individual or $55,500 for a family of four — residents at any income bracket could choose to buy into the program, paying sliding-scale premiums based on their income. After paying the income-based premiums, there will be no deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums, like there are in insurance programs on the individual market.

“Hopefully, in September, when I have my next appointment, I’ll have insurance. Fingers crossed.”

Paula Williams is a health care organizer at the Land Stewardship Project, a farm-focused non-profit in Minnesota that created a branch of their organization specifically to advocate for this health care bill. So how does this new option help farmers?

Health insurance is consistently one of the biggest expenses in the profession. Anne Schwagerl, vice president of the Minnesota Farmers Union and an organic grain farmer herself, said her members lament about it all the time.

“We’re disproportionately purchasing our health care on the independent market, and that ends up being more expensive for less coverage because we’re not in an employer pool,” she said.

Gary Wertish, president of the Minnesota Farmers Union, agreed that the issue was top of mind for the union’s members. In a statement, he said farmers often tell him, “If we really want to help agriculture, you can do something about health care — not only to help current farmers but to pass on to the next generation.”

To stay insured, farmers can be left facing difficult decisions.

“We had to limit the size of our farming operation in order to continue to qualify for public subsidies for health care.”

In an effort to avoid getting kicked off the affordable insurance plans, some have been forced to purposefully keep their farms less profitable, and control their income level so they remain under the low-income insurance cap — something both VanDerPol and Schwagerl said they had to do on their farms.

“There are farmers, myself included, who for many years, we had to limit the size of our farming operation in order to continue to qualify for public subsidies for health care,” said Schwagerl.

VanDerPol has also had to watch her farm’s finances closely. Even in the years her farm’s profitability increased on paper, that didn’t mean her family had those funds left over to pay thousands of dollars in deductibles.

“[The income] looks good on your taxes,” said VanDerPol. “The taxes say ‘You have this much income and you’re in this tax bracket,’ but that money is not in your checkbook, because you’ve put it back into your farm, because that’s how farming works.” So the years they didn’t qualify for the state-subsidized option, they went without insurance.

In addition to keeping their operations small to stay on their health care plan, some farmers opt to take off-farm jobs in hopes of acquiring affordable health insurance. In fact, according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture survey, “the majority of farm households have an operator or spouse employed off the farm,” and that’s how they get their insurance coverage.

This, said Williams, is a large reason the Land Stewardship Project got so involved, hosting events, hiring employees specifically to campaign for the bill’s passage, and advocating for health care options for farmers — to keep them on the farm.

The years they didn’t qualify for the state-subsidized option, they went without insurance.

“We decided we would fight for the ability for farmers to stay on the land, work on the land, and really do well at it, not stay under the poverty line, which a lot of our farmers do,” she said. The Land Stewardship Project offers programs primarily focused on regenerative farming practices, which require a lot of farmers’ time and energy. “You can’t do regenerative farming practices, you can’t implement cover crops, you can’t implement all these new things that require more time and energy just to get them implemented if you have to work off of the farm.”

Another aspect of the bill particularly helpful for farmers is allowing undocumented immigrants access to the state’s affordable health care program — regardless of immigration status and income level.

“Immigrants, undocumented or documented, are an integral part of our food and farming systems,” said Williams, which is a large part of why the Land Stewardship project championed the immigrant inclusion policy. According to the Minnesota Department of Health Services, approximately 300,000 Minnesotans are uninsured, 17% of whom are undocumented.

For Minnesota, the next step is to conduct something called an “actuarial analysis,” a large study to determine how much the implementation of the program will cost. That step will also produce predicted numbers of how many Minnesotans will sign up for the program, and what the income-based premiums will cost, exactly. But no matter the outcome of this analysis, the bill’s passage won’t be impacted. The downside? The plan won’t go into effect until 2027.

Despite the wait time and remaining uncertainty around the details of the program, the bill’s passage is considered a win for Minnesota farmers and the organizations like The Minnesota Farmers Union and the Land Stewardship Project that have been pushing for this for years. There are years to go before Minnesota farmers will see the bill’s benefits but, in the meantime, it can offer hope.

“I’m just very thankful that this is … becoming a reality,” said VanDerPol. “Maybe not in time for my husband and me, but for our kids, our grandkids. I hope they don’t have to have the same worries that we did.”