Small-scale cannabis cultivators hoping to profit from legalization struggle with hurdles and headaches, while backyard hobbyists enjoy worry-free harvests.

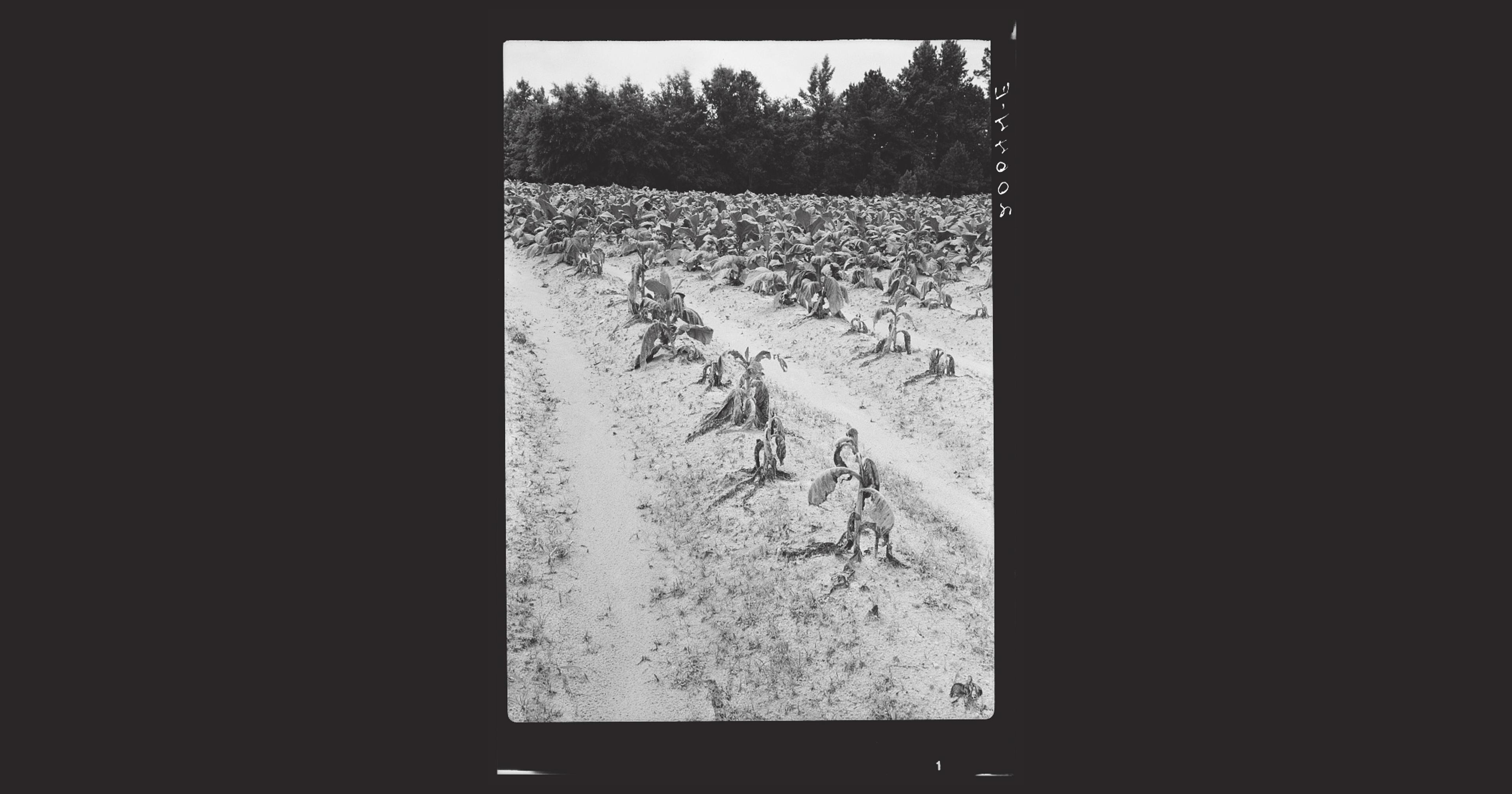

It’s September in Maine, and the year is 2016. The leaves of the swamp maples are beginning to turn transparent gold, and while the days remain dusty and hot, the nights are crisp with frost. Most people’s gardens are being put to bed, the last of the tomatoes picked and the pumpkins harvested. It is time to start processing the cannabis crop.

Growing cannabis for recreational use was illegal in Maine in 2016 — but that did not mean it wasn’t grown. If you grew cannabis there, it is likely you did so in one of two ways. You could have an indoor grow operation that would produce year-round, with lights and heaters and air conditioners all humming away. Indoor grows at this time were often large, clandestine operations filling an abandoned chicken coop or an old warehouse, but they could be as small as a single plant in a cultivator’s closet.

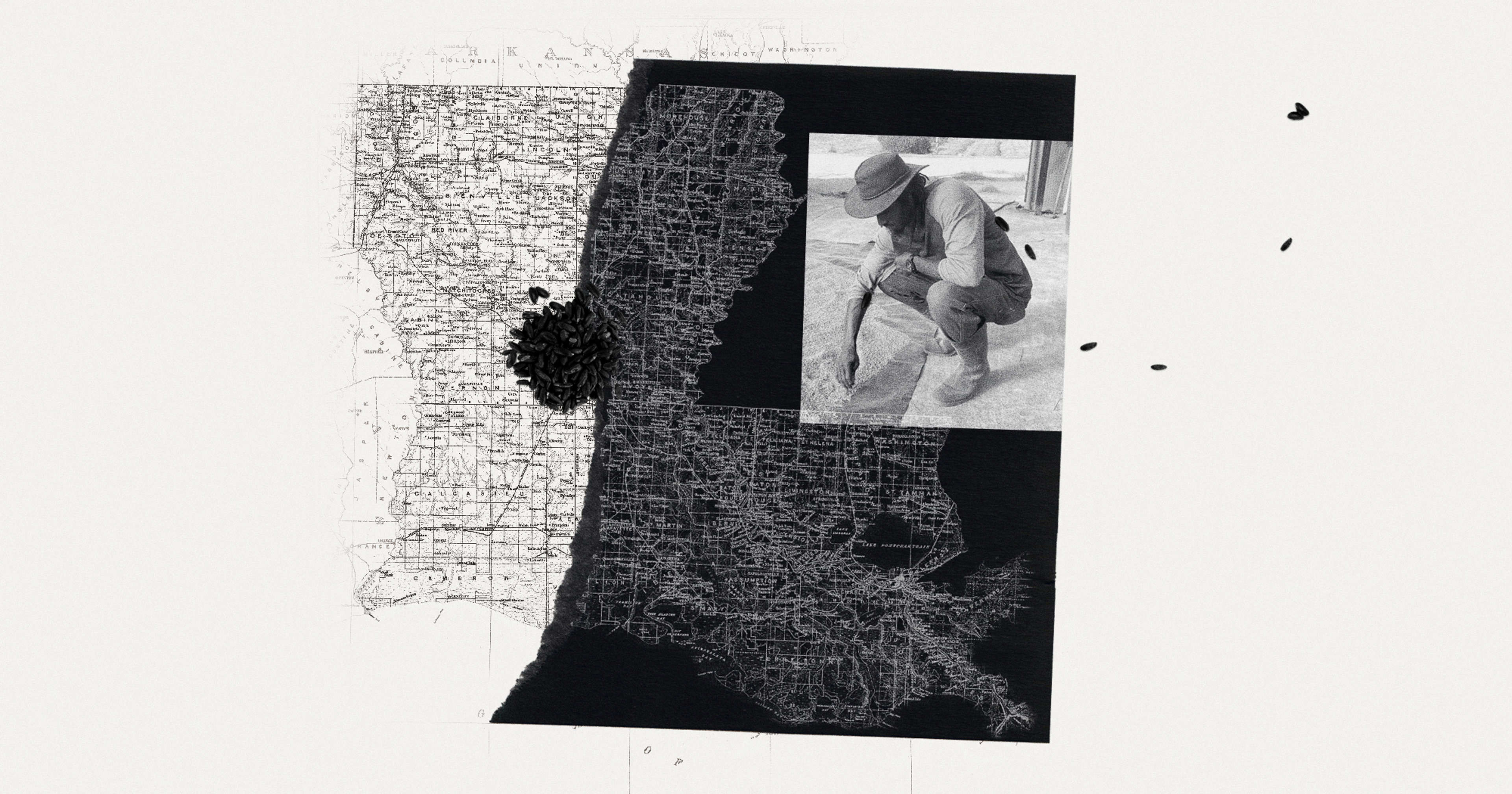

You also might grow outdoors, an easier and more environmentally friendly method. Maine’s climate does not allow for year-round growing, but it does produce beautiful seasonal marijuana. Most outdoor grows were nestled in woodlots and forests at the ends of walking paths or ATV trails. These operations, too, could be anywhere from a couple of plants to several dozen. The paths into them were hidden, unmarked, and their locations kept secret except to the growers themselves.

But the most bold — or foolhardy — growers might just put a few plants in their garden. Nosy neighbors were a concern, because a rubbernecking passerby could make a phone call to law enforcement, and land the grower in jail for growing even one cannabis plant.

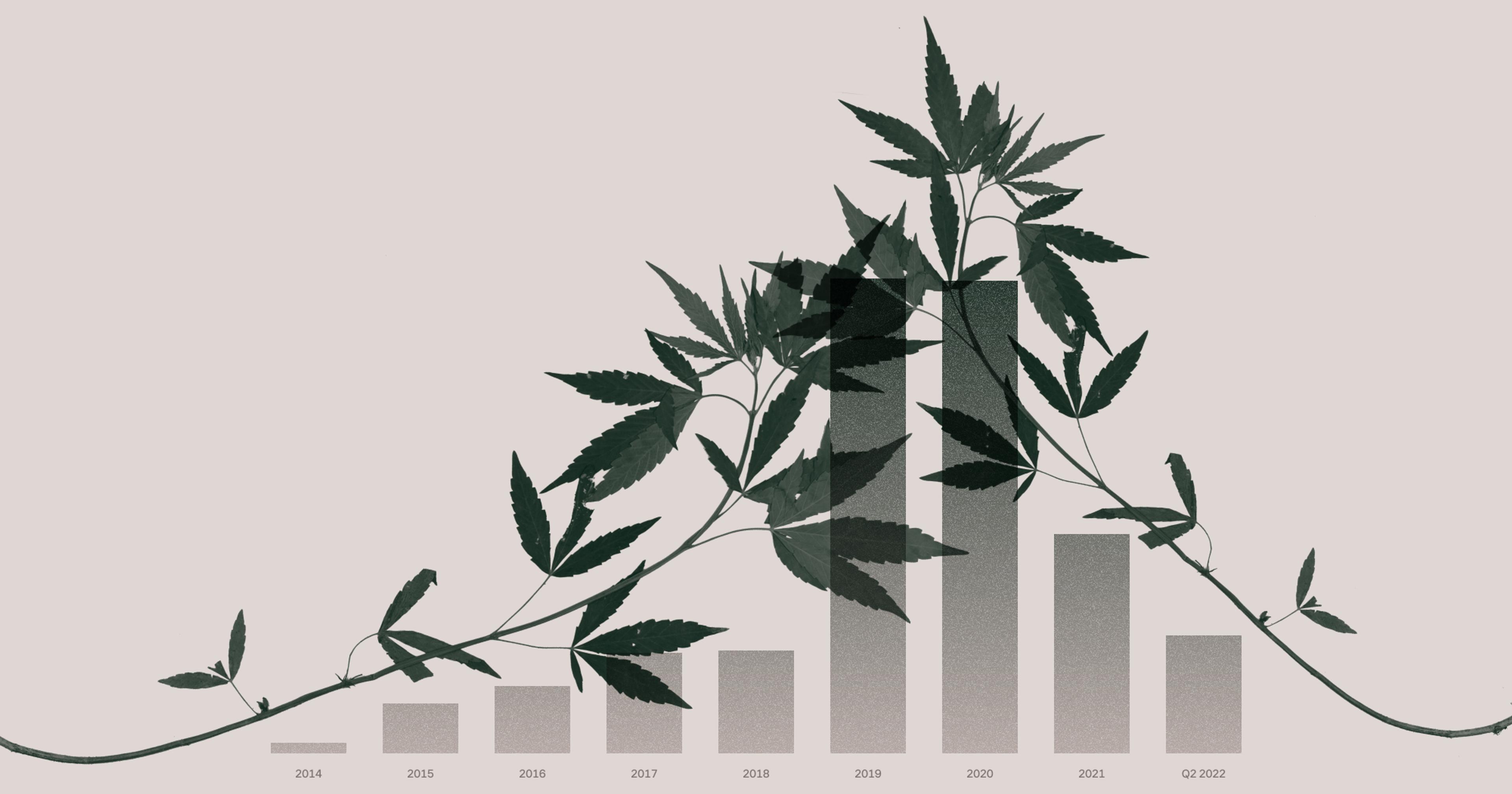

In November of 2016, Maine voters approved the limited legalization of recreational marijuana in Maine. It was one of four states to approve ballot measures on recreational growing that year, following Colorado and Washington which passed legalization measures in 2012. Today, recreational growing is legal in 24 U.S. states.

“If you were lucky you could get a pound off a single plant, so with five or six plants you could pay your bills, cover the mortgage for another year, or take a nice vacation.”

In Maine, you can now grow three mature plants per adult in your household, smoke cannabis if you are over the age of 21, and purchase recreational marijuana from dispensaries and storefronts. The impacts of legalization have been far-reaching and often unexpected. When you walk down the street you might catch a whiff of weed from someone’s joint or you may spot a plant in someone’s backyard. You will notice an explosion of head shops, cannabis stores, and growing supply companies in legal states, all hoping to make it rich in the “green rush.” Large commercial grows have appeared in open fields and empty spaces. But somewhere in between the hundreds of plants that make up a commercial grow and the one or two in someone’s backyard, there used to be a medium-sized grower making a small profit.

Before legalization passed, backyard growers were putting themselves at risk. But many of them were also generating income. You didn’t have to run a large operation to benefit from black-market marijuana: Even a grower with a few plants in their backyard could make several thousand dollars a year in tax-free income.

“Back then, a pound of cannabis was worth over $2000,” a former grower who wished to remain anonymous explains. “If you were lucky you could get a pound off a single plant, so with five or six plants you could pay your bills, cover the mortgage for another year, or take a nice vacation.”

“It was easy to get used to that income,” the source admits. “Now if you’re just trying to sell on the street you’d be lucky to get a quarter of what you did back then, if you can sell it at all. Everyone has leftover weed; you can’t give the stuff away.”

If a former black-market grower wanted to become legal in Maine, they’d have to pay a $100 application fee and get approval from the state of Maine. Maine growers can apply for one of four tiers depending on how often they wish to renew their license and how much growing space they are going to use. If approved, a Tier One grower then has to pay $9-17 per plant as they grow.

California legalized growing recreational cannabis in 2016, after having medical growing laws since 1996. You might expect that the famous mecca of weed, Humboldt County, would be overjoyed by their freshly legal status. After all, they didn’t have to hide what they were doing anymore. But former illegal growers have hesitated to embrace their new legitimacy.

“If you’re a small grower, you’ll always have struggles because you aren’t the one with the capital to invest.”

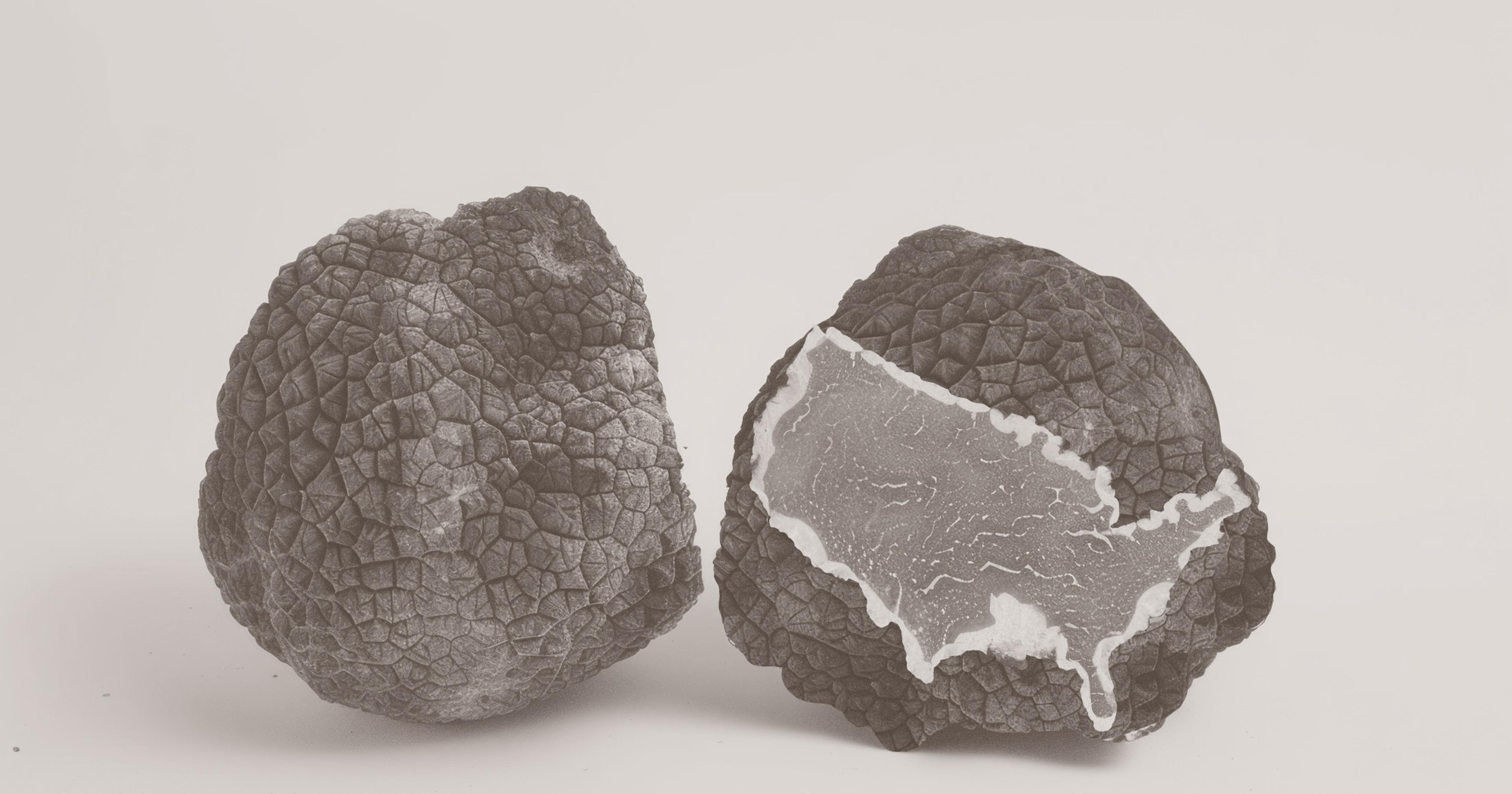

A comprehensive 2021 study for the Journal of Rural Studies found that of the cannabis growers in California who didn’t apply to go legal, almost half made that decision because they couldn’t see a financial incentive. To gain legal status as a grower and seller of marijuana in California, the application process is lengthy and expensive with fees well over $1000, depending on the number of plants you intend to grow. According to the study, growers believed that the application process was biased against small and “legacy” (former legal medical) growers.

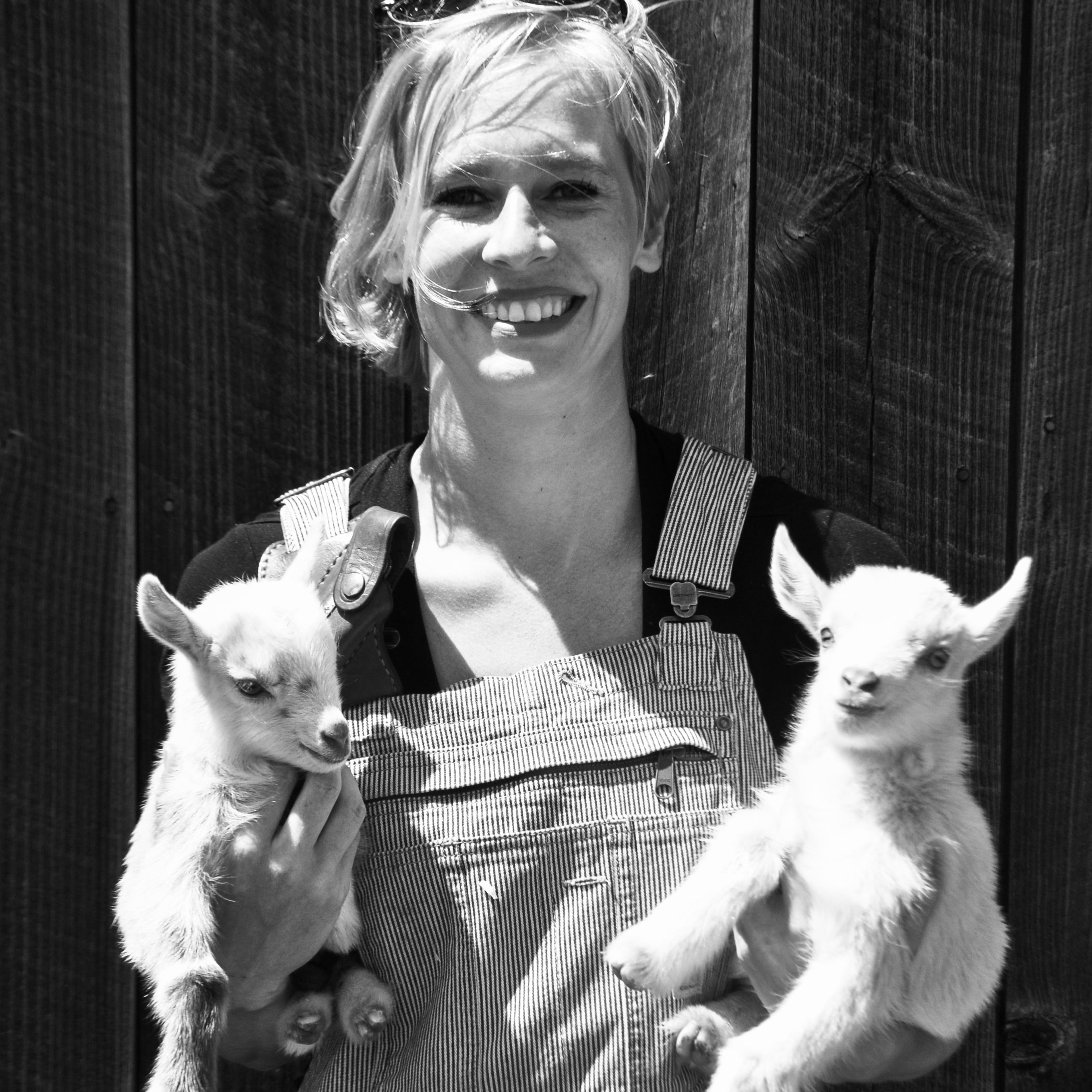

Some Maine cannabis growers agree with this sentiment. “If you’re a small grower,” said Amy McFarland, former president of Maine Cannabis Union and head of Independence Farm, “you’ll always have struggles because you aren’t the one with the capital to invest.”

The majority of commercial marijuana is grown indoors, where the environment is controlled and cannabis can be grown year-round. The infrastructure behind an indoor grow starts with a large floor space, either in warehouse buildings or purpose-built greenhouses. A 2017 study with Oregon State University found that land prices and competition for farm labor had increased with legalization, as had competition for leased greenhouse space.

But assuming you don’t want to turn a profit, the fundamental change from black-market growing to legal status has been a liberating one. A spokesperson for Harry Brown’s Farm in Starks, Maine, said that the biggest impact they’ve seen “has been that [Harry] can grow cannabis in his garden instead of the woods, and his farm has not dealt with the DEA and Maine State Police flying over his farm.” Harry Brown’s Farm, while not a commercial growing operation, has been a gathering place for Maine cannabis growers and enthusiasts for over 30 years.

As September rolls around again, many Maine growers are once again headed out to tend their marijuana plants, now nestled next to their homes or in their kitchen gardens. Cannabis requires care and attention just like tomatoes and potatoes. The eager grower is currently staking the large branches up and removing excess fan leaves to allow light to filter through and help it develop the largest possible buds: the pride and joy of any marijuana grower.

While some cannabis growers are doing this under harsh grow lights in warehouses full of thousands of plants, plenty of today’s cultivators are everyday gardeners stepping off their back porch with garden clippers in hand, making their way through their zinnias and cucumbers, unafraid of snooping neighbors or potential calls to the law. By late September, as everything else in the garden withers and turns brown, the cannabis plant will be brilliant green and heavy with purple, gold, and white buds ready for harvest.

The legalization of cannabis has brought about a sea change in every state it has been ratified in. If you step into a dispensary or storefront, you’re likely buying from a large corporate grow operation, with little connection to whoever farmed it. But backyard growers know exactly where their cannabis comes from.